8 High-Risk Cardiac Catheterization

Since its inception, heart catheterization has evolved from a diagnostic modality used for hemodynamic assessment and visualization of the coronary anatomy and ventricular function to a therapeutic means to treat pathology, from atherosclerosis to congenital heart defects. More than 1.5 million catheterizations are performed in the United States each year. Complication rates for diagnostic procedures in the catheterization laboratory principally include death, myocardial infarction, stroke, vascular complications, contrast reactions, or arrhythmia. The rates for these complications are very low and have not changed over the past decade (Table 8-1). As the procedure continues to mature, a comfort level has developed in performing procedures on higher risk patients. It is becoming more common for patients to undergo multivessel (including left main) percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with hemodynamic support as an elective procedure within most catheterization laboratories.

Table 8-1 Risk of Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Angiography

| Complication | Risk (%) |

|---|---|

| Mortality | 0.11 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.05 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 0.07 |

| Arrhythmia | 0.38 |

| Vascular complications | 0.43 |

| Contrast reaction | 0.37 |

| Hemodynamic complications | 0.26 |

| Perforation of heart chamber | 0.03 |

| Other complications | 0.28 |

| Total of major complications | 1.70 |

Adapted from Scanlon PJ, Faxon DP, Audet AM, et al: ACC/AHA guidelines for coronary angiography: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Coronary Angiography), JACC 33:1760, 1999.

High-Risk Patient: Definition

Patients classified as high risk are more likely to die or have myocardial infarction or ventricular fibrillation during cardiac catheterization than are other patients. Numerous studies have summarized the clinical and anatomic characteristics of patients at high risk: patients with known significant three-vessel or left main coronary artery disease, severe left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, diabetes, existing arrhythmias, or poorly controlled hypertension (Table 8-2). Patients with high-risk features from stress testing, including ventricular dilatation with stress and a large amount of ischemia myocardium, are at higher risk secondary to the higher likelihood of these patients to have multivessel or left main coronary disease. Patients with congestive heart failure, recent acute myocardial infarction, unstable angina, and severe valvular heart disease (especially critical aortic stenosis) have a high incidence of morbidity and mortality during and after cardiac catheterization. The occurrence of major complications in the cardiac catheterization laboratory has increased with the increasing complexity of interventional procedures.

Table 8-2 Variables Increasing the Risk of Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Angiography

| Anatomic | Clinical |

|---|---|

| Acute myocardial Infarction ± cardiogenic shock | |

| Left main coronary disease | Atrial/ventricular arrhythmias |

| Three-vessel obstructive disease | Poorly controlled hypertension |

| Decompensated heart failure (especially NYHA class IV) | |

| Severe valvular disease (especially severe aortic stenosis) | Diabetes mellitus |

| Severe left ventricular dysfunction (EF <30%) | Renal insufficiency |

| Pulmonary disease (COPD, asthma, OSA) | |

| Severe peripheral vascular disease (vascular access difficulty is also included) | Anemia ± bleeding diathesis, active GI bleeding, elevated INR, thrombocytopenia |

| Cerebrovascular disease | |

| Saphenous vein grafts | IV contrast allergy |

| Females (?) | Age >60 yr or <1 yr |

| Very small or very large body habitus | |

| Emergent procedure |

COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EF, ejection fraction; GI, gastrointestinal; INR, international normalized ratio; IV, intravenous; NYHA, New York Heart Association; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

Prevention of Complications

Meticulous attention to the precatheterization patient assessment and recognition of potential risks decreases procedure-related complications.

Patient Medications

Many medications may affect the patient’s catheterization risk (Table 8-3).

Table 8-3 Medications That May Impact Cardiac Catheterization Risk

| Warfarin |

| Furosemide |

| Metformin |

| Insulin (especially long acting) |

| Sildenafil/Vardenafil/Tadalafil |

| ACE inhibitors (lisinopril, ramipril, enalapril) |

| ARBs (losartan, candesartan) |

| NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen) |

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

Radiographic Contrast Media

The use of iodinated contrast must always be considered a potential source of complications in patients undergoing catheterization. There are multiple contrast agents currently available, and differentiating between them requires knowledge of their characteristics (see Chapter 4) and recognition of their chemical and trade names. Low osmolar and nonionic contrast agents are associated with a lower incidence of bradycardia, hypotension, and myocardial ischemia developing in the patient, and these agents are now routinely used during cardiac catheterizations. Almost all cardiac catheterizations today are routinely performed with nonionic, low-osmolality agents.

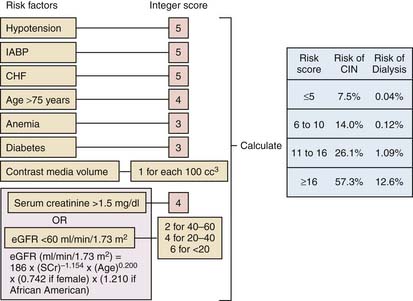

Contrast-induced renal insufficiency represents the leading cause of in-hospital acute renal failure and is discussed in detail in Chapter 4. Several risk factors have been identified that are found in patients at higher likelihood of developing contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) (Table 8-4). Unfortunately, many of these parameters are not changeable and therefore do not lend themselves as potential ways to avoid CIN. A risk score has been devised identify patients at higher risk for CIN and is shown in Figure 8-1. Prophylactic strategies to decrease the risk of CIN center around three strategies: maintaining adequate intravascular volume, limiting the amount of contrast delivered, and avoiding medications that could exacerbate renal dysfunction.

Table 8-4 Risk Factors for Development of Contrast-Induced Nephropathy

| Patient Related | Extrinsic | Possible |

|---|---|---|

| Existing renal insufficiency (est GFR <60/ml/min/1.73 m2) | Contrast volume administered | Metabolic syndrome |

| Congestive heart failure | High osmolal contrast | Diabetes |

| Diabetes with existing renal insuff. | Intraaortic balloon pump used | Impaired glucose tolerance |

| Age >70 yr | Nephrotoxic drugs | Hyperuricemia |

| Volume depletion | Multiple contrast administrations (within 72 hr) | ACEi or ARB |

| Hypotension | Urgent/emergent PCI | Female gender |

| Anemia | Multiple myeloma | |

| Hypertension | Cirrhosis | |

| Peripheral vascular disease |

ACEi, Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; est, estimated; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; insuf., insufficiency; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Modified from Klein et al, The use of radiographic contrast media during PCI: A focused review. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent 2009; 74:728.

There are many protocols that have been published that outline how to ensure adequate hydration. The most commonly cited formula uses 0.9% normal saline for 12 hours before and 12 hours after the procedure. Sodium bicarbonate for hydration also is commonly used (154 ml of 1000 mEq/L sodium bicarbonate to 846 ml of 5% dextrose with an initial intravenous (IV) bolus of 3 ml/kg per hour for 1 hour immediately before contrast followed by a rate of 1 ml/kg per hour during the contrast exposure and for 6 hours after the procedure). Data supporting the use of acetylcysteine (600 mg orally twice daily the day before and day of the procedure), although modest, suggest that it can be considered for patients at high risk of contrast nephropathy. Many other pharmacologic treatments (including furosemide, mannitol, dopamine, and fenoldopam) have not been shown to be effective or even have caused more harm and should not be used.

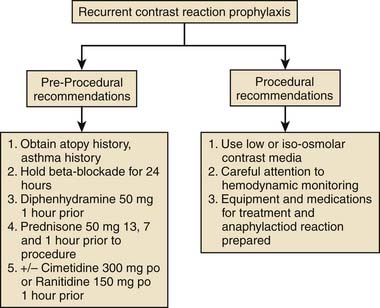

Allergic reactions to contrast are discussed in Chapter 1. It is worth remembering that these reactions are characterized as “anaphylactoid” in that they do not require previous exposure to contrast (and thus circulating IgE) to exist but do occur as a result of mast cell degranulation. A patient with a history of multiple food and drug allergies and, of course, those that have had previous reactions to contrast are especially at high risk. The perception that patients having a seafood or shellfish allergy also are at higher risk has never been shown to be true and should not be used as criteria to administer prophylaxis for contrast reactions.

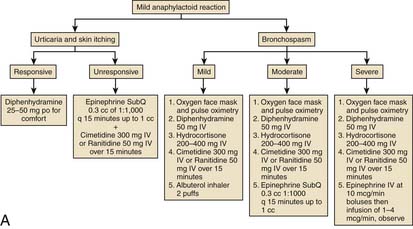

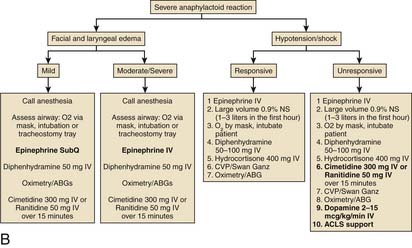

Prophylaxis for patients who are at risk for reactions to contrast media should include prednisone and diphenhydramine. Figure 8-2 depicts treatment algorithms for mild and severe reactions.

Figure 8-2 Treatment paradigm to guide prophylaxis against contrast-induced allergic reactions.

(From Klein LW, Sheldon MW, Brinker J, et al: Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent 74:731, 2009, fig 1c.)

Thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia (low platelet count) is a troublesome finding on the preprocedural laboratory work. If thrombocytopenia is medication related, that medication should be stopped. A more difficult scenario is the patient with end-stage liver disease who has significant splenic sequestration of platelets. The platelet count is often less than 50,000. There is debate as to whether transfusing platelets before the procedure is helpful because transfused platelets are rapidly consumed and are not available to aid in clotting. Platelet transfusions, if done, should occur during the procedure and not before. For patients at high risk of bleeding, one should consider radial artery access. Of course, the nonaccess site bleeding risks remain the same.

Management of Complications During Cardiac Catheterization

Complications of coronary arteriography in high-risk patients must be managed at once (Table 8-5).

Table 8-5 Management of Complications During Cardiac Catheterization

| Complications and Precautions | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Ventricular tachycardia, asystole, or fibrillations (0.6%) | Use nonionic contrast agents in high-risk patients |

| Cough for temporary increase in BP | |

| Remove catheter from RV, LV, or coronary ostium | |

| Do not wedge coronary artery catheter; contrast material washout should be brisk; ECG and BP should be normal before next injection | |

| CPR followed by prompt defibrillation (200J) | |

| Do not inject when catheter tip pressure is damped | |

| Lidocaine (50 mg bolus, 2 to 4 mg/min IV) | |

| Use atropine, volume expansion, or infusion | |

| Amiodarone (300 mg bolus) then metaraminol (Aramine) for hypotension | |

| Refractory VF usually as a result of extensive CAD; emergency percutaneous cardiopulmonary bypass should be considered | |

| Limit contrast medium injected into coronary arteries; avoid prolonged injections | |

| Air embolism (0.1%) | Prevention: careful back bleeding and flushing of all connections. Make sure all connections tight. |

| Treatment: 100% oxygen,fluids, aspiration, ACLS if indicated. | |

| Hematoma in femoral artery (0.1% major, 1% to 2% minor) | Puncture below inguinal ligament inferior epigastric artery and above bifurcation of superficial and profunda femotal arteries |

| Evacuation rarely required | |

| Attention to compression | |

| Surgical consult for enlarging hematoma, compartment syndrome, or cool extremity | |

| Prolonged compression if patient coughing, or has aortic insufficiency, hypertension, or heparin not reversed | |

| Vascular closure device | |

| Retroperitoneal bleeding | Avoid high (above IEA) femoral artery puncture |

| Reverse anticoagulants | |

| Volume replacement | |

| Watch for hypotension, low abdominal or flank pain within 2-12 hr of procedure. Low hematocrit, tachycardia (if not receiving beta-blockers) | |

| Transfusion if hematocrit <25 | |

| Surgical consultation | |

| CT scan |

BP, Blood pressure; CAD, coronary artery disease; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram; IEA, inferior epigastric artery; IV, intravenous; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; VF, ventricular fibrillation.