Chapter 46 Hernias

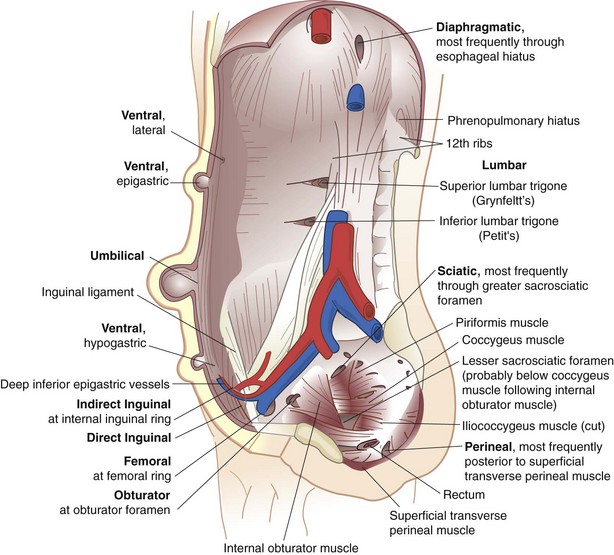

Hernia is derived from the Latin word for rupture. A hernia is defined as an abnormal protrusion of an organ or tissue through a defect in its surrounding walls. Although a hernia can occur at various sites of the body, these defects most commonly involve the abdominal wall, particularly the inguinal region. Abdominal wall hernias occur only at sites at which the aponeurosis and fascia are not covered by striated muscle (Box 46-1). These sites most commonly include the inguinal, femoral, and umbilical areas, linea alba, lower portion of the semilunar line, and sites of prior incisions (Fig. 46-1). The so-called neck or orifice of a hernia is located at the innermost musculoaponeurotic layer, whereas the hernia sac is lined by peritoneum and protrudes from the neck. There is no consistent relationship between the area of a hernia defect and the size of a hernia sac.

FIGURE 46-1 Types of abdominal wall hernias.

(From Dorland’s illustrated medical dictionary, ed 31, Philadelphia, 2007, WB Saunders, Plate 21.)

Inguinal Hernias

Anatomy of the Groin

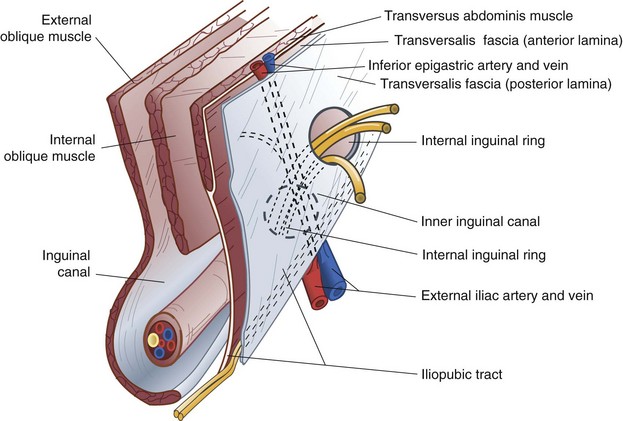

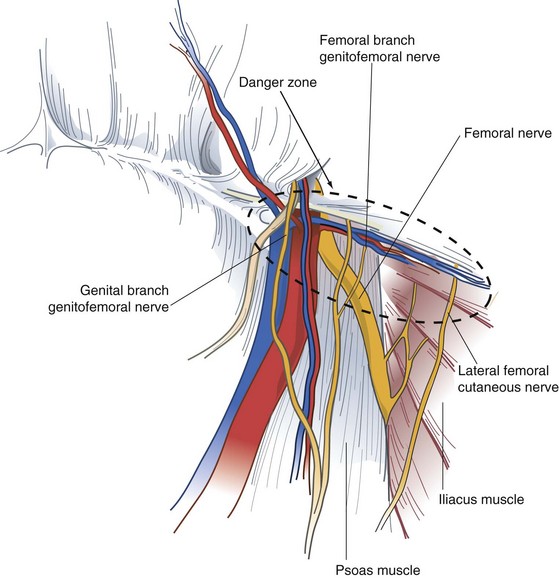

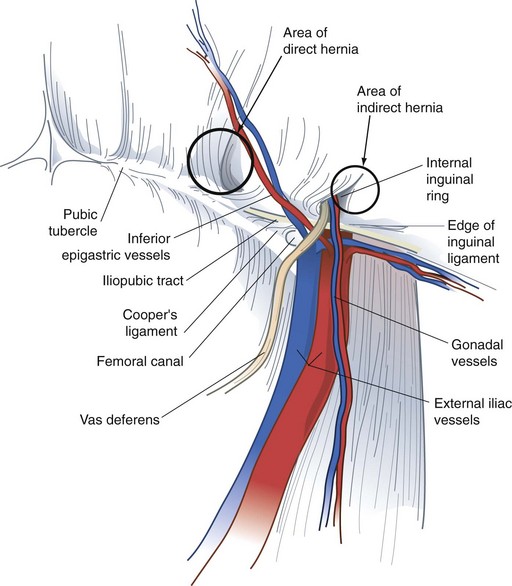

The surgeon must have a comprehensive understanding of the anatomy of the groin to select and use various options for hernia repair properly. In addition, the relationships of muscles, aponeuroses, fascia, nerves, blood vessels, and spermatic cord structures in the inguinal region must be completely understood to obtain the lowest incidence of recurrence and avoid complications. These anatomic considerations must be understood from the anterior and posterior approaches because both are useful in different situations (Figs. 46-2 and 46-3).

FIGURE 46-3 Anatomy of the important preperitoneal structures in the right inguinal space.

(From Talamini MA, Are C: Laparoscopic hernia repair. In Zuidema GD, Yeo CJ [eds]: Shackelford’s surgery of the alimentary tract, ed 5, vol 5, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders, p 140.)

Inguinal Canal

The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves and genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve are the important sensory nerves in the groin area (Fig. 46-4). The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves provide sensation to the skin of the groin, base of the penis, and ipsilateral upper medial thigh. The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves lie beneath the internal oblique muscle to a point just medial and superior to the anterior superior iliac spine, where they penetrate the internal oblique muscle and course beneath the external oblique aponeurosis. The main trunk of the iliohypogastric nerve runs on the anterior surface of the internal oblique muscle and aponeurosis medial and superior to the internal ring. The iliohypogastric nerve may provide an inguinal branch that joins the ilioinguinal nerve. The ilioinguinal nerve runs anterior to the spermatic cord in the inguinal canal and branches at the superficial inguinal ring. The genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve innervates the cremaster muscle and skin on the lateral side of the scrotum and labia. This nerve lies on the iliopubic tract and accompanies the cremaster vessels to form a neurovascular bundle.

Diagnosis

A bulge in the inguinal region is the main diagnostic finding in most groin hernias. There may be associated pain or vague discomfort in the region, but groin hernias are usually not extremely painful unless incarceration or strangulation has occurred. In the absence of physical findings, alternative causes for pain need to be considered. Occasionally, patients may experience paresthesias related to compression or irritation of the inguinal nerves by the hernia. Masses other than hernias can occur in the groin region. Physical examination alone often differentiates between a groin hernia and these masses (Box 46-2).

Box 46-2 Differential Diagnosis of Groin and Scrotal Masses

Hidradenitis of inguinal apocrine glands

Ultrasonography also can aid in the diagnosis. There is a high degree of sensitivity and specificity for ultrasound in the detection of occult direct, indirect, and femoral hernias.1 Other imaging modalities are less useful. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis may be useful for the diagnosis of obscure and unusual hernias as well as atypical groin masses.2 Occasionally, laparoscopy can be diagnostic and therapeutic for particularly challenging cases.

Classification

There are numerous classification systems for groin hernias. One simple and widely used system is the Nyhus classification (Box 46-3). Although their purpose is to promote a common language and understanding for physician communication and to allow appropriate comparisons of therapeutic options, these classifications are incomplete and contentious. Most surgeons continue to describe hernias by their type, location, and volume of the hernia sac.

Treatment

Nonoperative Management

Most surgeons recommend operation on discovery of a symptomatic inguinal hernia because the natural history of a groin hernia is that of progressive enlargement and weakening, with a small potential for incarceration and strangulation. However, in patients with minimal symptoms, the clinician is often faced with balancing the risk for hernia-related complications such as incarceration and bowel strangulation, with the potential for complications in the short and long term. Fitzgibbons and colleagues3 have reported a prospective randomized trial of a watchful waiting strategy for men with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias. These investigators randomized more than 700 men to a watchful waiting or open tension-free hernia repair. At 2 years of follow-up, there were no deaths attributed to the study and the risk for hernia incarceration in the watchful waiting group was extremely low, 0.3% of study participants or 1.8 events/1000 patient-years. Almost 25% of patients assigned to watchful waiting crossed over to the surgical group, usually for pain related to the hernia that limited activity. Despite the seemingly high crossover rate, those patients, who later had surgery, did not have increased surgical site infections, longer operative times, or higher recurrence rates than those who were initially assigned to early repair. This study provides conclusive evidence that a strategy of watchful waiting is safe for older patients with asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias and that even though almost 25% of patients eventually undergo repair, when they do, the operative risks and complication rates are no different than those of patients undergoing prophylactic repair. Watchful waiting also is a cost-effective management strategy for patients with no or minimal symptoms.

Operative Repair

Tissue Repairs

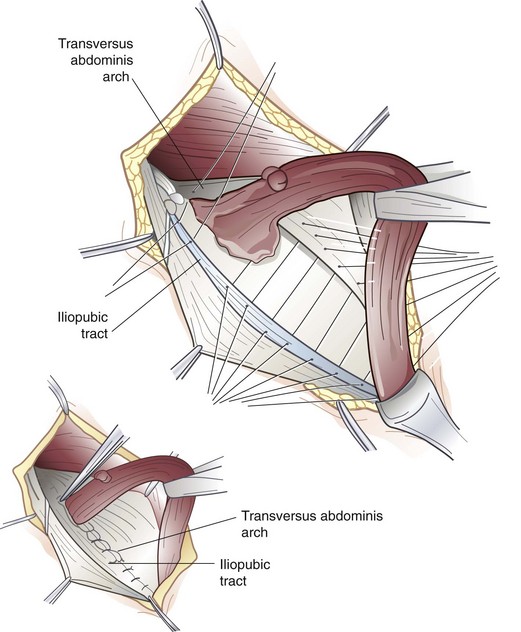

The iliopubic tract repair approximates the transversus abdominis aponeurotic arch to the iliopubic tract with the use of interrupted sutures (Fig. 46-5). The repair begins at the pubic tubercle and extends laterally past the internal inguinal ring. This repair was initially described using a relaxing incision (see later); however, many surgeons who use this repair do not perform a relaxing incision.

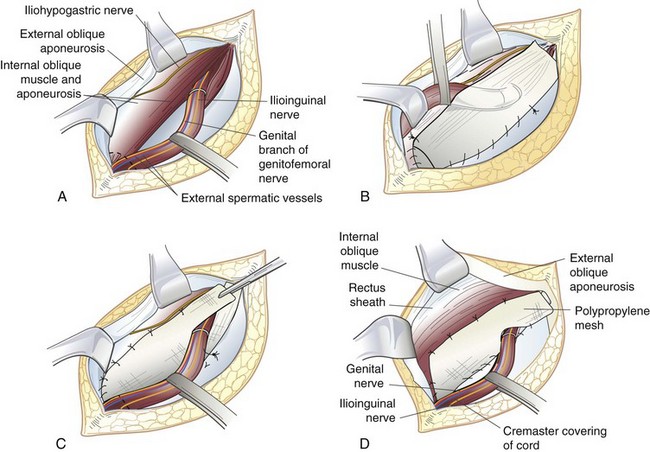

Tension-Free Anterior Inguinal Hernia Repair

The tension-free repair has become the dominant method of inguinal hernia repair (Fig. 46-6). Recognizing that tension in a repair is the principal cause of recurrence, current practices in hernia management use a synthetic mesh prosthesis to bridge the defect, a concept popularized by Lichtenstein. There are several options for placement of mesh during anterior inguinal herniorrhaphy, including the Lichtenstein approach, plug and patch technique, and sandwich technique, with both an anterior and preperitoneal piece of mesh.

In the Lichtenstein repair,4 a piece of prosthetic nonabsorbable mesh is fashioned to fit the canal. A slit is cut into the distal lateral edge of the mesh to accommodate the spermatic cord. There are various preformed, commercially available prostheses available for use. Monofilament nonabsorbable suture is used to secure the mesh, beginning at the pubic tubercle and running a length of suture in both directions toward the superior aspect above the internal inguinal ring to the level of the tails of the mesh. The mesh is sutured to the aponeurotic tissue overlying the pubic bone medially, continuing superiorly along the transversus abdominis or conjoined tendon. The inferolateral edge of the mesh is sutured to the iliopubic tract or shelving edge of the inguinal ligament to a point lateral to the internal inguinal ring. At this point, the tails created by the slit are sutured together around the spermatic cord, snugly forming a new internal inguinal ring. It is important to protect the ilioinguinal nerve and genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve from entrapment by placing them with the cord structures as they are passed through this newly fashioned internal inguinal ring or avoiding their enclosure in the repair.

Adapting the principles of tension-free repair, Gilbert5 has reported using a cone-shaped plug of polypropylene mesh that when inserted into the internal inguinal ring, would deploy like an upside-down umbrella and occlude the hernia. This plug is sewn to the surrounding tissues and held in place by an additional overlying mesh patch. This patch may not need to be secured by sutures; however, to do so requires dissection to create a sufficient space between the external and internal oblique muscles for the patch to lie flat over the inguinal canal. This so-called plug and patch repair, an extension of Lichtenstein’s original mesh repair, has now become the most commonly performed primary anterior inguinal hernia repair. Although this repair can be done without suture fixation by some experienced surgeons, most secure plug and patch with several monofilament nonabsorbable sutures, especially for very weak inguinal floors or large defects.

Another option for a tension-free mesh repair involves a preperitoneal approach using a self-expanding polypropylene patch.6 A pocket is created in the preperitoneal space by blunt dissection and then a preformed mesh patch is inserted into the hernia defect, which expands to cover the direct, indirect, and femoral spaces. The patch lies parallel to the inguinal ligament. It can remain without suture fixation, or a tacking suture can be placed.

The Stoppa-Rives repair uses a subumbilical midline incision to place a large mesh prosthesis into the preperitoneal space.7 Blunt dissection is used to create an extraperitoneal space that extends into the prevesical space, beyond the obturator foramen, and posterolateral to the pelvic brim. This technique has the advantage of distributing the natural intra-abdominal pressure across a broad area to retain the mesh in a proper location. The Stoppa-Rives technique is particularly useful for large, recurrent, or bilateral hernias.

Preperitoneal Repair

The open preperitoneal approach is useful for the repair of recurrent inguinal hernias, sliding hernias, femoral hernias, and some strangulated hernias.8 A transverse skin incision is made 2 cm above the internal inguinal ring and is directed to the medial border of the rectus sheath. The muscles of the anterior abdominal wall are incised transversely and the preperitoneal space is identified. If further exposure is needed, the anterior rectus sheath can be incised and the rectus muscle retracted medially. The preperitoneal tissues are retracted cephalad to visualize the posterior inguinal wall and the site of herniation. The inferior epigastric artery and veins are generally beneath the midportion of the posterior rectus sheath and usually do not need to be divided. This approach avoids mobilization of the spermatic cord and injury to the sensory nerves of the inguinal canal, which is particularly important for hernias previously repaired through an anterior approach. If the peritoneum is incised, it is sutured closed to avoid the evisceration of intraperitoneal contents into the operative field. The transversalis fascia and transversus abdominis aponeurosis are identified and sutured to the iliopubic tract with permanent sutures. Femoral hernias repaired by this approach require closure of the femoral canal by securing the repair to Cooper’s ligament. A mesh prosthesis is frequently used to obliterate the defect in the femoral canal, particularly with large hernias.

Laparoscopic Repair

Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair is another method of tension-free mesh repair, based on a preperitoneal approach. The laparoscopic approach provides the mechanical advantage of placing a large piece of mesh behind the defect covering the myopectineal orifice and using the natural forces of the abdominal wall to support the mesh in place. Proponents have touted quicker recovery, less pain, better visualization of anatomy, usefulness for fixing all inguinal hernia defects, and decreased surgical site infections. Critics have emphasized longer operative times, technical challenges, risk of recurrence, and increased cost. Although controversy exists about the usefulness of laparoscopic repair for primary unilateral inguinal hernias, most agree that this approach has advantages for patients with bilateral or recurrent hernias.9 Adopting practice guidelines for the performance of laparoscopic hernia repairs could help control costs.

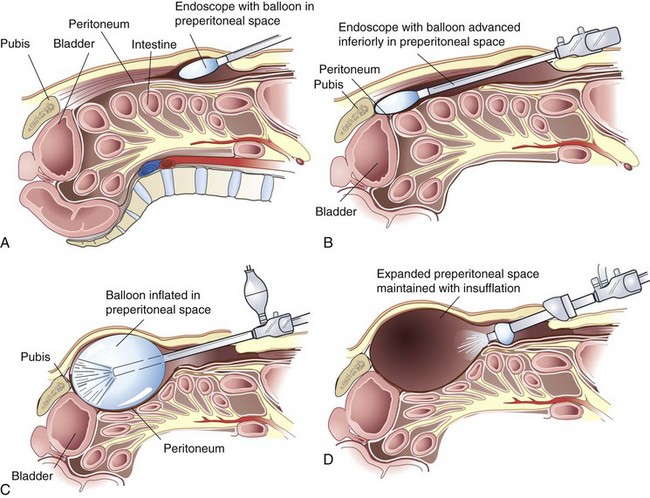

In the TEP approach, an infraumbilical incision is used. The anterior rectus sheath is incised, the ipsilateral rectus abdominis muscle is retracted laterally, and blunt dissection is used to create a space beneath the rectus. A dissecting balloon is inserted deep to the posterior rectus sheath, advanced to the pubic symphysis, and inflated under direct laparoscopic vision (Fig. 46-7). After it is opened, the space is insufflated and additional trocars are placed. A 30-degree laparoscope provides the best visualization of the inguinal region (see Fig. 46-3). The inferior epigastric vessels are identified along the lower portion of the rectus muscle and serve as a useful landmark. Cooper’s ligament must be cleared from the pubic symphysis medially to the level of the external iliac vein. The iliopubic tract is also identified. Care must be taken to avoid injury to the femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, which are located lateral to and below the iliopubic tract (see Fig. 46-4). Lateral dissection is carried out to the anterior superior iliac spine. Finally, the spermatic cord is skeletonized.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree