21 Hereditary Cardiomyopathies

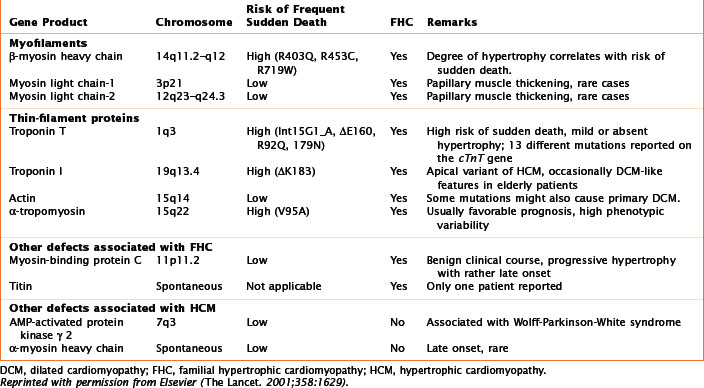

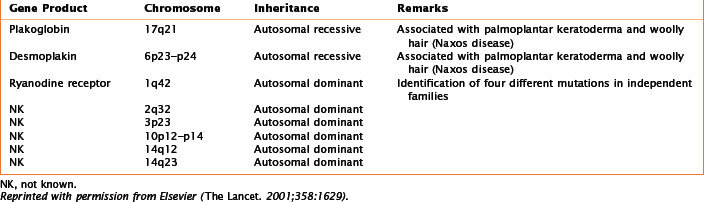

Numerous genetic mutations, either de novo or with a clear familial transmission, are associated with each of these categories of cardiomyopathy. A familial cause has been found in about 50% of patients with HCM, 35% with DCM, and 30% with ARVC (Tables 21-1, 21-2, and 21-3). As yet, no specific genetic mutations have been found in restrictive cardiomyopathy; however, it is likely that genetic abnormalities predisposing to restrictive cardiomyopathy will be found, given the numerous reports of families with multiple cases of the disease.

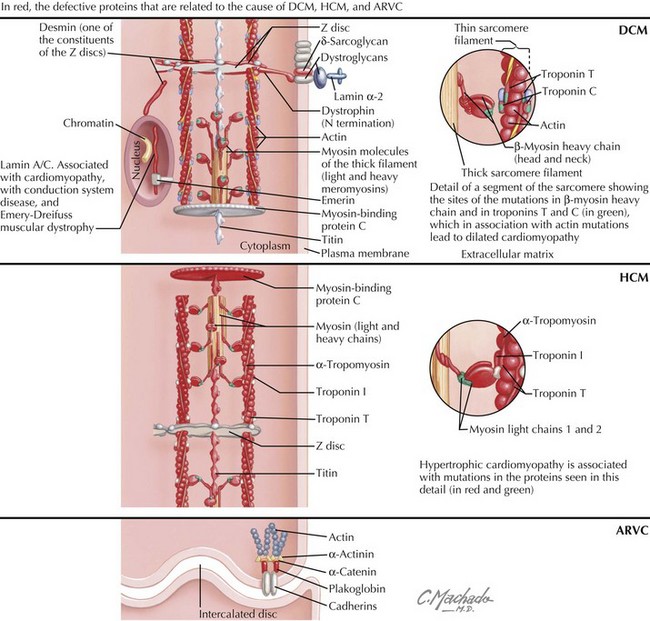

The first evidence of a gene defect associated with an intrinsic heart muscle disease was published in 1990. The discovery of a mutation in the gene encoding the β-myosin heavy chain (Table 21-1; Fig. 21-1), with resultant familial HCM, was followed by discoveries of gene mutations for the entire spectrum of cardiomyopathies. This chapter focuses on the breadth of mutations that affect the myocardium, whereas Chapter 72 addresses the general topic of genetics in cardiovascular diseases.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

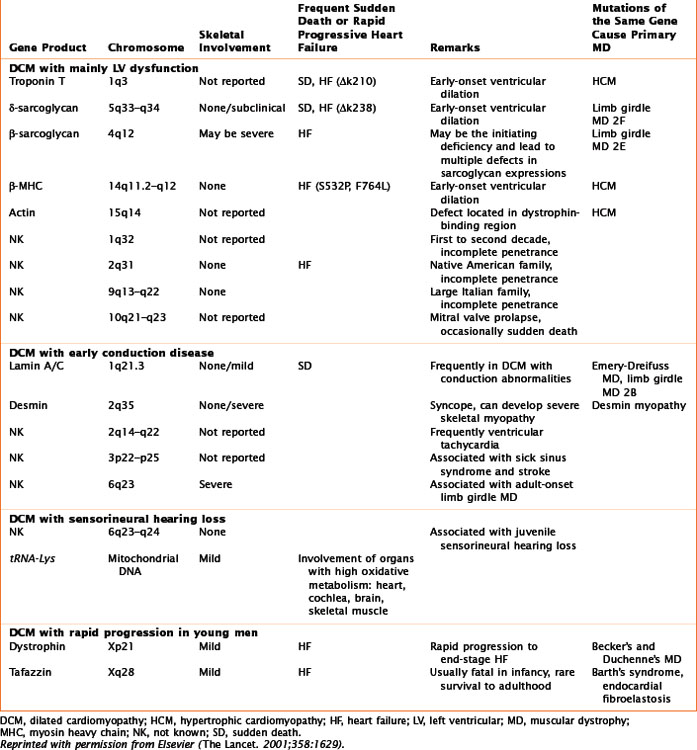

Familial Dilated Cardiomyopathy

The phenotype for familial DCM is divided into three groups (Table 21-2; Fig. 21-1), two that are based on the type of genetic transmission and Barth’s syndrome (previously included among “X-linked” cardiomyopathies), which is considered a third group because of its peculiar mitochondrial involvement.

Autosomal-Dominant Transmission

Autosomal-dominant transmission accounts for most cases of familial DCM, which may present either as heart failure or as a conduction abnormality. Ten genetic loci have been mapped for cardiomyopathy without conduction system disease. Seven of these genes are known: actin (chromosome 15q14), desmin (chromosome 2q35), δ-sarcoglycan (chromosome 5q33), β-sarcoglycan (chromosome 4q12), cardiac troponin T (chromosome 1q3), β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC, chromosome 14q11), and α-tropomyosin (chromosome 15q22); see Table 21-1. Mutations in the α-tropomyosin gene are associated with familial HCMs. Actin, a sarcomeric protein, leads to DCM if the mutation affects its binding to dystrophin (at the sarcolemma level) or to HCM if the mutation affects the myosin-binding region. Mutations of the β-MHC and of cardiac troponin T genes are thought to produce DCM by causing reduced force generation by the sarcomere. In particular, the β-MHC mutation disrupts interactions between actin and myosin or with a hinge area within myosin that transmits movement. Mutations in cardiac troponin T decrease the power of contraction by reducing the ionic interactions between cardiac troponins T and C. The α-tropomyosin mutation interferes with the integrity of the thin filaments. Other mutations are involved either with the stability of the sarcomere or the sarcolemma, or with signal transduction.

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Familial HCM with autosomal-dominant inheritance encompasses most of the cases of HCM (see Table 21-1; Fig. 21-1). The first gene for familial HCM was mapped to chromosome 14q11.2–14q12. Familial HCM can be caused by mutations in nine different genes encoding sarcomere proteins expressed in cardiac muscle. There are now more than 100 point mutations in the sarcomeric proteins known to cause HCM.