Hemoptysis

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

• Hemoptysis refers to the expectoration of blood originating from the lower airway or lung.

• Massive hemoptysis is defined as the expectoration of large amounts of blood.

There is no consensus on the volume of blood needed to be classified as massive but definitions range from 100 to > 600 mL over a 24-hour period.

There is no consensus on the volume of blood needed to be classified as massive but definitions range from 100 to > 600 mL over a 24-hour period.

Massive hemoptysis can be life threatening and should be considered a medical emergency. Death is usually from asphyxiation or exsanguination with flooding of the alveoli resulting in refractory hypoxemia.

Massive hemoptysis can be life threatening and should be considered a medical emergency. Death is usually from asphyxiation or exsanguination with flooding of the alveoli resulting in refractory hypoxemia.

Massive hemoptysis accounts for about 1–5% of all patients presenting with hemoptysis.

Massive hemoptysis accounts for about 1–5% of all patients presenting with hemoptysis.

• The most common causes of hemoptysis in the United States are bronchitis, bronchiectasis, bronchogenic carcinoma, TB, and pneumonia.

• The pulmonary circulation consists of dual blood supplies: the pulmonary and bronchial artery systems.

The pulmonary artery system is a low-pressure system with pressures of 15–20/5–10 mm Hg. It delivers blood from the right ventricle to the pulmonary capillary beds for oxygenation and returns it to the left atrium via the pulmonary veins.

The pulmonary artery system is a low-pressure system with pressures of 15–20/5–10 mm Hg. It delivers blood from the right ventricle to the pulmonary capillary beds for oxygenation and returns it to the left atrium via the pulmonary veins.

The bronchial arteries arise from the aorta and thus exhibit systemic pressures. There are one or two bronchial arteries per lung and these arteries are the main source of nutrients and oxygenation of the lung tissue and hilar lymph nodes.

The bronchial arteries arise from the aorta and thus exhibit systemic pressures. There are one or two bronchial arteries per lung and these arteries are the main source of nutrients and oxygenation of the lung tissue and hilar lymph nodes.

• In patients with normal pulmonary artery pressures, bleeding from the pulmonary arterial system only accounts for ∼5% of massive hemoptysis cases.

• Mortality risk factors identified for in-hospital mortality include mechanical ventilation, pulmonary artery bleeding, cancer, aspergillosis, chronic alcoholism, and an admission CXR with infiltrates in more than two quadrants.1

DIAGNOSIS

• A thorough history, physical examination, and laboratory evaluation can help determine the correct etiology of the hemoptysis and clarify the best diagnostic procedure.

• Processes that could be confused with hemoptysis, such as hematemesis or bleeding from the upper airway, must first be eliminated.

Clinical Presentation

• Important historical points to cover include prior lung, cardiac, or renal disease, history of smoking cigarettes, prior hemoptysis, pulmonary symptoms, infectious symptoms, family history of hemoptysis or brain aneurysms (hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia), chemical exposures (asbestos, organic chemicals), travel history, TB exposures, bleeding disorders, use of anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents, and gastrointestinal or upper airway complaints.

• Signs that may aid in diagnosis include telangiectasias (hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia), skin rashes (vasculitis, rheumatologic diseases, infective endocarditis), splinter hemorrhages (endocarditis, vasculitis), clubbing (chronic lung disease, carcinoma), bruits that increase with inspiration (large arteriovenous [AV] malformations), cardiac murmurs (endocarditis, mitral stenosis, congenital heart disease), and lower extremity edema (deep vein thrombosis).

Differential Diagnosis

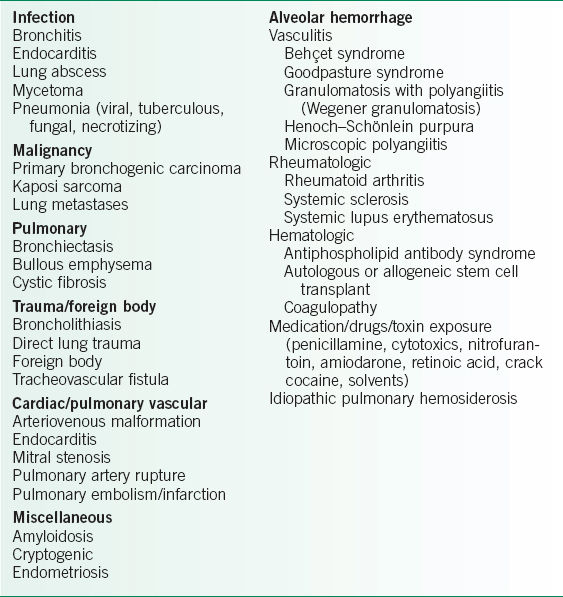

The differential diagnosis of hemoptysis is presented in Table 18-1 (also see Chapter 19).

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratories

• Complete blood count: to assess the magnitude and acuity of bleeding and for thrombocytopenia.

• Renal function and urinalysis: to look for evidence of pulmonary-renal syndromes.

• Coagulation profile: to assess for the presence of a coagulopathy.

• Pulse oximetry and an arterial blood gas: to assess oxygenation.

TABLE 18-1 CAUSES OF HEMOPTYSIS

Imaging

• The three traditional methods of evaluating the etiology of hemoptysis include CXR, CT scan, and bronchoscopy.

• Performing a CXR first is reasonable for the majority of patients. Findings may lead to at least localization of the site of bleeding.

A negative CXR may not be very helpful, depending on the clinical picture. For example, a nonsmoking young patient with a relatively small amount of transient hemoptysis in the setting of acute bronchitis and a normal CXR likely does not require further evaluation.

A negative CXR may not be very helpful, depending on the clinical picture. For example, a nonsmoking young patient with a relatively small amount of transient hemoptysis in the setting of acute bronchitis and a normal CXR likely does not require further evaluation.

In other patients a normal CXR does not eliminate the possibility of a serious cause, including malignancy.2

In other patients a normal CXR does not eliminate the possibility of a serious cause, including malignancy.2

Further imaging (usually CT scan) is appropriate in patients with hemoptysis >30 mL or >40 years old and >30 pack-years of smoking, persistent/recurrent hemoptysis <30 mL and >40 years old or >30 pack-years of smoking, and in patients with massive hemoptysis (>300–400 mL).2–6

Further imaging (usually CT scan) is appropriate in patients with hemoptysis >30 mL or >40 years old and >30 pack-years of smoking, persistent/recurrent hemoptysis <30 mL and >40 years old or >30 pack-years of smoking, and in patients with massive hemoptysis (>300–400 mL).2–6

• High-resolution CT

The sensitivity of high-resolution CT (HRCT) scanning is better than CXR, particularly for certain diagnoses, such as bronchiectasis.7–9

The sensitivity of high-resolution CT (HRCT) scanning is better than CXR, particularly for certain diagnoses, such as bronchiectasis.7–9

HRCT has better diagnostic yield (i.e., abnormal finding leading to a specific diagnosis) when compared to bronchoscopy alone in some studies.2,9–11

HRCT has better diagnostic yield (i.e., abnormal finding leading to a specific diagnosis) when compared to bronchoscopy alone in some studies.2,9–11

Diagnostic Procedures

• Bronchoscopy

The overall diagnostic yield of bronchoscopy specifically for hemoptysis is difficult to say with precision, likely depends on patient population, and may be fairly low. In a study by Gong et al., flexible bronchoscopy in the acute setting versus delayed has been shown to be more likely to visualize active bleeding (41% vs. 8%) or the site of bleeding (34% vs. 11%).12

The overall diagnostic yield of bronchoscopy specifically for hemoptysis is difficult to say with precision, likely depends on patient population, and may be fairly low. In a study by Gong et al., flexible bronchoscopy in the acute setting versus delayed has been shown to be more likely to visualize active bleeding (41% vs. 8%) or the site of bleeding (34% vs. 11%).12

In patients with abnormal, but nonlocalizing CXRs, the diagnostic yield reported by Hirshburg et al. was 34–55%. In the patients with moderate to severe hemoptysis, bronchoscopy was able to localize the site of bleeding in ∼65% of patients. Bronchoscopy combined with CT scanning had a diagnostic yield of 93%.7

In patients with abnormal, but nonlocalizing CXRs, the diagnostic yield reported by Hirshburg et al. was 34–55%. In the patients with moderate to severe hemoptysis, bronchoscopy was able to localize the site of bleeding in ∼65% of patients. Bronchoscopy combined with CT scanning had a diagnostic yield of 93%.7

In patients with localizing CXR, the yield of bronchoscopy has been as high as 82%.13

In patients with localizing CXR, the yield of bronchoscopy has been as high as 82%.13

• Flexible bronchoscopy versus rigid bronchoscopy in the setting of massive hemoptysis.

Flexible bronchoscopy has the advantage of better visualization of airways, ability to navigate into small subsegments, and can be performed at the bedside. However, suctioning blood is inferior with flexible bronchoscopy compared to that with rigid bronchoscopy.

Flexible bronchoscopy has the advantage of better visualization of airways, ability to navigate into small subsegments, and can be performed at the bedside. However, suctioning blood is inferior with flexible bronchoscopy compared to that with rigid bronchoscopy.

Rigid bronchoscopy usually requires operating room resources, only allows direct visualization of larger airways, but bleeding can be better controlled and therapeutic interventions can be performed.

Rigid bronchoscopy usually requires operating room resources, only allows direct visualization of larger airways, but bleeding can be better controlled and therapeutic interventions can be performed.

TREATMENT

• Nonmassive hemoptysis: treat the underlying cause (i.e., antibiotics for an infection, radiation therapy or laser therapy for an endobronchial tumor).

• Massive hemoptysis: management of massive hemoptysis should focus on airway protection and stabilization, localization of bleeding, and bleeding control. A patient with massive hemoptysis should be observed in the intensive care unit (ICU,) even if not intubated.

• Airway protection and stabilization

If the location is known, the patient should be placed in the lateral decubitus position with the affected side down.

If the location is known, the patient should be placed in the lateral decubitus position with the affected side down.

The patient with massive hemoptysis often requires intubation. The patient can be selectively (right or left) intubated on the nonbleeding side.

The patient with massive hemoptysis often requires intubation. The patient can be selectively (right or left) intubated on the nonbleeding side.

Selective intubation can be performed using a double-lumen endotracheal (ET) tube, selective mainstem intubation using a standard ET tube into the nonbleeding lung, or a standard ET tube in the trachea with a Fogarty catheter placed around the ET tube into the bleeding lung.

Selective intubation can be performed using a double-lumen endotracheal (ET) tube, selective mainstem intubation using a standard ET tube into the nonbleeding lung, or a standard ET tube in the trachea with a Fogarty catheter placed around the ET tube into the bleeding lung.

If bleeding occurs in the left lung, it is not advised to place a standard ET tube into the right mainstem bronchus due to the proximal position of the right upper lobe bronchus takeoff and high risk of right upper lobe collapse. Instead, a double-lumen ET tube or an ET tube in the trachea with placement of a Fogarty catheter are preferable. Placement of a Fogarty catheter is often done using a bronchoscope.

If bleeding occurs in the left lung, it is not advised to place a standard ET tube into the right mainstem bronchus due to the proximal position of the right upper lobe bronchus takeoff and high risk of right upper lobe collapse. Instead, a double-lumen ET tube or an ET tube in the trachea with placement of a Fogarty catheter are preferable. Placement of a Fogarty catheter is often done using a bronchoscope.

Both positioning and selective intubation are used to prevent aspiration of blood into the nonbleeding lung.

Both positioning and selective intubation are used to prevent aspiration of blood into the nonbleeding lung.

It is important to remember that blood clots in the large bronchi can be life threatening even without large decreases in hematocrit.

It is important to remember that blood clots in the large bronchi can be life threatening even without large decreases in hematocrit.

The use of strong cough suppressants (e.g., opiates) can also be helpful.

The use of strong cough suppressants (e.g., opiates) can also be helpful.

Large-bore IV access should be obtained and fluid resuscitation should be started.

Large-bore IV access should be obtained and fluid resuscitation should be started.

• Localization of the bleeding

Localization is very important in the management of massive hemoptysis.

Localization is very important in the management of massive hemoptysis.

Localization can be attempted using the imaging and diagnostic procedures listed in the previous section in addition to a careful pulmonary examination.

Localization can be attempted using the imaging and diagnostic procedures listed in the previous section in addition to a careful pulmonary examination.

The presence of rhonchi or wheezes on examination might suggest the site of bleeding.

The presence of rhonchi or wheezes on examination might suggest the site of bleeding.

• Control of bleeding

First, the patient’s medication list should be reviewed for anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin, dabigatran, etc.) or platelet inhibitors (e.g., aspirin, clopidogrel), and these medications should be held at least until bleeding is controlled.

First, the patient’s medication list should be reviewed for anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin, dabigatran, etc.) or platelet inhibitors (e.g., aspirin, clopidogrel), and these medications should be held at least until bleeding is controlled.

If a coagulopathy is present, it should be corrected with the use of appropriate factor replacement and platelet transfusions.

If a coagulopathy is present, it should be corrected with the use of appropriate factor replacement and platelet transfusions.

In patients with a history of renal failure, consider desmopressin for possible platelet dysfunction.

In patients with a history of renal failure, consider desmopressin for possible platelet dysfunction.

Once bronchoscopy has been performed to localize the site of bleeding, therapeutic options can be performed through the bronchoscope, including iced saline lavage, topical epinephrine, endobronchial tamponade, and laser photocoagulation.

Once bronchoscopy has been performed to localize the site of bleeding, therapeutic options can be performed through the bronchoscope, including iced saline lavage, topical epinephrine, endobronchial tamponade, and laser photocoagulation.

• Pulmonary angiography and bronchial artery embolization by interventional radiology may also be attempted.

It is frequently used to try to stop massive hemoptysis or recurrent hemoptysis (from sources such as mycetomas). The short-term success rate of bronchial artery embolization is between about 65% and 95% but rebleeding can recur in a minority of patients.14–17

It is frequently used to try to stop massive hemoptysis or recurrent hemoptysis (from sources such as mycetomas). The short-term success rate of bronchial artery embolization is between about 65% and 95% but rebleeding can recur in a minority of patients.14–17

Bronchial artery embolization is contraindicated if the anterior spinal artery arises from the bronchial artery, as this could lead to spinal cord ischemia. The overall risk of spinal cord ischemic injury is <1%. Bronchoscopy prior to angiography is helpful in directing the radiologist to the affected area of lung and can allow for embolization of potential culprit vessels in the setting of a negative angiogram.

Bronchial artery embolization is contraindicated if the anterior spinal artery arises from the bronchial artery, as this could lead to spinal cord ischemia. The overall risk of spinal cord ischemic injury is <1%. Bronchoscopy prior to angiography is helpful in directing the radiologist to the affected area of lung and can allow for embolization of potential culprit vessels in the setting of a negative angiogram.

• Surgery

Surgery is a potential option for patient who can sustain a lobectomy or even pneumonectomy.

Surgery is a potential option for patient who can sustain a lobectomy or even pneumonectomy.

Mortality rates that have been reported vary between 1% and 50%.

Mortality rates that have been reported vary between 1% and 50%.

Thoracic surgery consultation and evaluation should be obtained early in an unstable hemoptysis patient.

Thoracic surgery consultation and evaluation should be obtained early in an unstable hemoptysis patient.

Operative complications include recurrence and spinal cord injury/ischemia due to disruption of the anterior spinal arteries.

Operative complications include recurrence and spinal cord injury/ischemia due to disruption of the anterior spinal arteries.

REFERENCES

1. Fartoukh M, Khoshnood B, Parrot A, et al. Early prediction of in-hospital mortality of patients with hemoptysis: an approach to defining severe hemoptysis. Respiration. 2012;83:106–14.

2. Thirumaran M, Sundar R, Sutcliffe IM, et al. Is investigation of patients with haemoptysis and normal chest radiograph justified. Thorax. 2009;64:854–6.

3. Poe RH, Israel RH, Marin MG, et al. Utility of fiberoptic bronchoscopy in patients with hemoptysis and a nonlocalizing chest roentgenogram. Chest. 1988;93:70–5.

4. O’Neil KM, Lazarus AA. Hemoptysis: indications for bronchoscopy. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:171–4.

5. Herth F, Ernst A, Becker HD. Long-term outcome and lung cancer incidence in patients with hemoptysis of unknown origin. Chest. 2001;120:1592–4.

6. Ketai LH, Mohammed TL, Kirsch J, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria hemoptysis. J Thorac Imaging. 2014;29:W19–22.

7. Hirshberg B, Biran I, Glazer M, et al. Hemoptysis: etiology, evaluation and outcomes in a tertiary hospital. Chest. 1997;112:440–4.

8. Tasker AD, Flower CD. Imaging the airways. Hemoptysis, bronchiectasis, and small airways disease. Clin Chest Med. 1999;20:761–73.

9. Revel MP, Fournier LS, Hennebicque AS, et al. Can CT replace bronchoscopy in the detection of the site and cause of bleeding in patients with large or massive hemoptysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1217–24.

10. Set PA, Flower DC, Smith IE, et al. Hemoptysis: comparative study of the role of CT and fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Radiology. 1993;189:677–80.

11. Laroche C, Fairbairn I, Moss H, et al. Role of computed tomographic scanning of the thorax prior to bronchoscopy in the investigation of suspected lung cancer. Thorax. 2000;55:359–63.

12. Gong H Jr, Salvatierra C. Clinical efficacy of early and delayed fiberoptic bronchoscopy in patients with hemoptysis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981;124:221–5.

13. Hsiao EI, Kirsch DM, Kagawa FT, et al. Utility of fiberoptic bronchoscopy before bronchial artery embolization for massive hemoptysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:861–7.

14. Cremaschi P, Nascimbene C, Vitulo P, et al. Therapeutic embolization of bronchial artery: a successful treatment in 209 cases of relapse hemoptysis. Angiology. 1993;44:295–9.

15. Jean-Baptiste E. Clinical assessment and management of massive hemoptysis. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1642–7.

16. Woo S, Yoon CJ, Chung JW, et al. Bronchial artery embolization to control hemoptysis: comparison of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate and polyvinyl alcohol particles. Radiology. 2013;269:594–602.

17. Larici AR, Franchi P, Occhipinti M, et al. Diagnosis and management of hemoptysis. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2014;20:299–309.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree