CHAPTER 1

Heart Failure Diagnosis and Epidemiology

—Eugene Braunwald, Shattuck Lecture 19971

Heart Failure Recognition

The diagnosis of heart failure may emerge from history, physical examination, or laboratory data.

CLINICAL CRITERIA OF HEART FAILURE

The Framingham study defined useful clinical criteria to identify patients with heart failure (Table 1.1). Patients not fulfilling the Framingham criteria can still have heart failure, albeit less severe disease, if they have symptoms of dyspnea or fatigue associated with structural or functional left ventricular abnormalities.2 Specifically, heart failure may be present when an individual has physical limitations at rest or with activity due to inadequate cardiac output or increased left or right ventricular filling pressures. Blood levels of biomarkers, such as B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), supplement clinical findings to characterize the presence and severity of heart failure.

TABLE 1.1 Framingham diagnostic criteria for heart failure. The diagnosis of heart failure, in the Framingham heart failure study, required two major or one major and two concurrent minor criteria. Minor criteria cannot be attributed to another medical condition.4 Source: Adapted from the New England Journal of Medicine, with permission.

MAJOR CRITERIA | MINOR CRITERIA |

Acute pulmonary edema | Dyspnea on exertion |

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea or orthopnea | Night cough |

Neck-vein distention | Tachycardia (> 120 beats/min) |

Rales | Pleural effusion |

S3 gallop | Hepatomegaly |

Abdominojugular reflux | Ankle edema |

Cardiomegaly on chest x-ray | Vital capacity decrease (1/3 from max) |

Increased venous pressure (> 16 cm H2O) | Weight loss* |

Weight loss* |

|

*Weight loss > 4.5 kg 5 days into treatment can be classified as a major or minor criterion

HEART FAILURE CLASSIFICATION

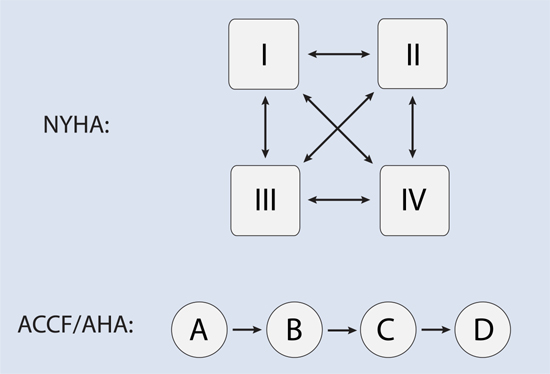

In 1928, the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification was proposed to classify the severity of heart failure based on symptoms.3 In this system, severity ranges from no limitation of functional activity (Class I), slight limitation of functional activity (Class II), marked limitation of functional activity (Class III), to the presence of symptoms at rest (Class IV). Although useful, to characterize a patient’s functional impairment at any point in time and provide an index that correlates with prognosis, the system is limited by the potential for a patient’s class to either worsen or improve rapidly in response to acute exacerbations or treatments (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 The ACCF/AHA stages of heart failure compared to the NYHA classification. Whereas NYHA functional class can wax and wane, the ACCF/AHA Stages (A–D) can only advance, usually with greater underlying structural and functional cardiac impairment.

Partly to address this potential for fluctuation in NYHA patient classification, in 2001 the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association published a four-component staging of heart failure in which progression occurs in only one direction encompassing risk factors (Stage A) to end-stage heart disease (Stage D).5 This classification was most recently updated in 2013.6 The previous New York Heart Association functional class, based solely on symptoms, can still describe the current functional status of a patient in Stages B through D. Especially in Stage C, however, any of the three symptomatic NYHA classifications (Class II, III, or IV) may repeatedly arise, resolve, and recur (Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2 The ACCF/AHA stages of heart failure compared to the NYHA classification. With treatment, a heart failure patient can become asymptomatic, but will remain Stage C.

Stage B is defined as development of structural heart disease in patients who never manifest symptoms or signs of heart failure.5 Most patients with a diagnosis of heart failure with either past or current symptoms are considered Stage C. Approximately 1% of patients with heart failure have progressed to an advanced Stage D.2

Epidemiology

Heart failure is increasing, particularly as a disease of aging. The prevalence also varies by race and ethnicity.

PANDEMIC OF HEART FAILURE

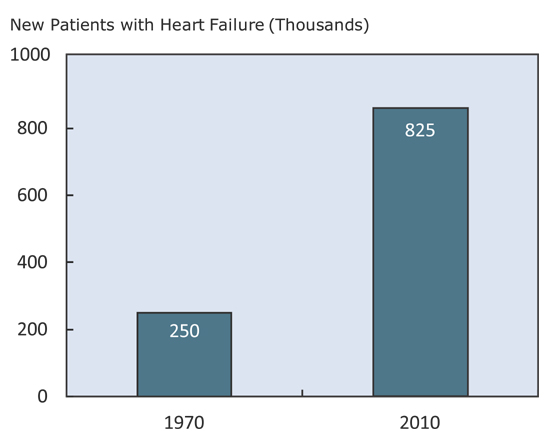

As patients survive the progression of acute and chronic cardiovascular disease, the subsequent development of heart failure accompanied by chronic, maladaptive ventricular remodeling becomes more common.7,8 Insults to the kidneys and peripheral vasculature contribute to this progression. Since 1970, in the United States, heart failure annual incidence has increased markedly (Figure 1.3).

FIGURE 1.3 Increase in incidence of heart failure in United States since 1970.9,10

HEART FAILURE AS A DISEASE OF AGING

After the age of 20, the prevalence of heart failure approximately doubles with each decade of life (Figure 1.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree