Heart Disease in Pregnancy

Basic principles

Cardiac disease in pregnancy is rare in the UK, Europe, and the developed world, but common in developing countries. In the UK, rheumatic heart disease is now extremely rare in women of childbearing age and is confined to immigrants. Women with congenital heart disease, having undergone corrective or palliative surgery in childhood, survive into adulthood, and are encountered more frequently. These women may have complicated pregnancies. Women with metal prosthetic valves face difficult decisions regarding anticoagulation in pregnancy. Ischaemic heart disease (IHD) is becoming more common in pregnancy, as the mean age of pregnancy increases and the smoking epidemic continues. Dissection of the aorta and its branches occurs more commonly in pregnancy, and pregnancy may cause a specific dilated cardiomyopathy— peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Despite its relative rarity, cardiac disease is the leading cause of maternal death in the UK, being responsible for 48 deaths in the three years 2003-2005 inclusive.1 The predominant cardiac causes of maternal death in the UK are peripartum cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction (MI), and dissection of the aorta and its branches.

Because of significant physiological changes in pregnancy, symptoms such as palpitations, and signs such as an ejection systolic murmur are very common and innocent findings. The care of the pregnant and parturient woman with heart disease requires a multidisciplinary approach and formulation of an agreed and documented management plan encompassing management of both planned and emergency delivery.

This chapter will cover the most important cardiac conditions relevant to pregnancy.

Physiological changes in pregnancy

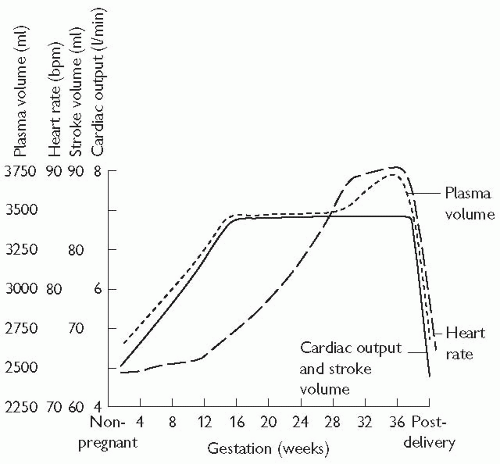

Cardiac output increases early in pregnancy, reaching a maximum by the mid-second trimester. This is achieved by an increase in both stroke volume and heart rate. There is peripheral vasodilation, and a fall in systemic and pulmonary vascular resistance.

Although there is no increase in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), serum colloid osmotic pressure is reduced. The colloid oncotic pressure-PCWP gradient is reduced by 28%, making pregnant women particularly susceptible to pulmonary oedema. Pulmonary oedema will be precipitated if there is either an increase in cardiac preload (such as infusion of fluids), or increased pulmonary capillary permeability (such as in pre-eclampsia), or both.

In late pregnancy, in the supine position, pressure of the gravid uterus on the inferior vena cava (IVC) causes a reduction in venous return to the heart and a consequent fall in stroke volume and cardiac output. Turning from the lateral to the supine position may result in a 25% reduction in cardiac output. Pregnant women should therefore be nursed in the left or right lateral position wherever possible. If the mother has to be kept on her back, the pelvis should be rotated so that the uterus drops forward, and cardiac output as well as uteroplacental blood flow are optimized. Reduced cardiac output is associated with reduction in uterine blood flow and therefore in placental perfusion; this can compromise the fetus.

Labour is associated with further increases in cardiac output (15 % in the first stage and 50% in the second stage). Uterine contractions lead to auto transfusion of 300-500 mL of blood back into the circulation, and the sympathetic response to pain and anxiety further elevates heart rate and blood pressure. Cardiac output is increased more during contractions but also between contractions.

Following delivery, there is an immediate rise in cardiac output due to the relief of IVC obstruction, and contraction of the uterus that empties blood into the systemic circulation. Cardiac output increases by 60-80%, followed by a rapid decline to pre-labour values within about one hour of delivery. Transfer of fluid from the extravascular space increases venous return and stroke volume further. Those women with cardiovascular compromise are therefore most at risk of pulmonary oedema during the second stage of labour and the immediate post-partum period.

See Fig. 15.1.

Physiological changes in the cardiovascular system in pregnancy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fig. 15.1 Physiological changes in pregnancy. Systemic and pulmonary vascular resistance fall during pregnancy. Blood pressure may fall in the second trimester, rising slightly in late pregnancy. Note the cardiac output and stroke volume peak by 16 weeks’ gestation. Reproduced with permission from Thorne SA (2004). Pregnancy in heart disease. Heart 90: 450-6. |

Normal findings in pregnancy

On examination

Findings may include:

bounding/collapsing pulse

ejection systolic murmur (present in over 90% pregnant women; may be quite loud, and audible all over the praecordium)

third heart sound

relative sinus tachycardia

ectopics

peripheral oedema.

On electrocardiogaphy (ECG)

These are partly related to changes in the position of the heart:

atrial and ventricular ectopics

Q wave (small) and inverted T wave in lead III

ST-segment depression and T-wave inversion inferior and lateral leads

QRS axis leftward shift.

Investigations

The amount of radiation received by the fetus during a maternal chest X-ray (CXR) is negligible and CXRs should never be withheld if clinically indicated in pregnancy.

Transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiograms are also safe, with the usual precautions to avoid aspiration.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is safe in pregnancy.

Routine investigation with electrophysiological studies and angiography is normally postponed until after pregnancy but should not be withheld in, for example, acute coronary syndromes.

General considerations in pregnancy

The heart has relatively less reserve than the respiratory system. Women with heart disease may not be able to increase their cardiac output adequately to cope with pregnancy and delivery.

The outcome and safety of pregnancy are related to the:

presence and severity of pulmonary hypertension

presence of cyanosis

haemodynamic significance of the lesion

Cardiac events such as stroke, arrhythmia, pulmonary oedema, and death complicating pregnancies are predicted by:2

a prior cardiac event or arrhythmia

NYHA classification >II

cyanosis

left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <40%

left heart obstruction (mitral valve area <2 cm2, aortic valve area <1.5 cm2, aortic valve gradient > 30 mmHg).

Women with congenital heart disease are at increased risk of having a baby with congenital heart disease, and should therefore be offered detailed scanning for fetal cardiac anomalies.

Women with cyanosis (oxygen saturation <80-85%) have an increased risk of fetal growth restriction, fetal loss, and thromboembolism secondary to the reactive polycythaemia. Their chance of a live birth in one study was less than 20%.3

Women with the above risk factors for adverse cardiac or obstetric events should be managed and counselled by a multidisciplinary team, including cardiologists with expertise in pregnancy, obstetricians, fetal medicine specialists, and paediatricians. Regular antenatal visits and judicious monitoring to avoid or treat expediently any anaemia or infection or cardiac decompensation are essential. There should be early involvement of obstetric anaesthetists and a carefully documented plan for delivery.

Pulmonary hypertension and pregnancy

Pulmonary vascular disease, whether secondary to a reversed large left-to-right shunt such as a ventral septal defect (VSD; Eisenmenger’s syndrome) or to lung or connective tissue disease (e.g. scleroderma), or due to primary pulmonary hypertension, is extremely dangerous in pregnancy. Women known to have pulmonary vascular disease should be advised from an early age to avoid pregnancy and be given appropriate contraceptive advice. Maternal mortality is 25-40%.12 Most fatalities occur in the early puerperium. The danger relates to fixed pulmonary vascular resistance and an inability to increase pulmonary blood flow with refractory hypoxaemia. Most deaths can be attributed to thromboembolism, hypovolaemia or pre-eclampsia.

Pulmonary hypertension is defined as a non-pregnant elevation of mean (not systolic) pulmonary artery pressure equal to or greater than 25 mmHg at rest or 30 mmHg on exercise in the absence of a left-to-right shunt. Pulmonary artery systolic (not mean) pressure is usually estimated by using Doppler ultrasound to measure the regurgitant jet velocity across the tricuspid valve. This should be considered a screening test. There is no agreed relation between the mean pulmonary pressure and the estimated systolic pulmonary pressure. If the systolic pulmonary pressure estimated by Doppler is thought to indicate pulmonary hypertension, a specialist cardiac opinion is recommended. If there is pulmonary hypertension in the presence of a left-to-right shunt, the diagnosis of pulmonary vascular disease is particularly difficult and further investigation including cardiac catheterization to calculate PVR is likely to be necessary. Pulmonary hypertension as defined by Doppler studies may also occur in mitral stenosis and with large left to right shunts that have not reversed and, although such women may not have pulmonary vascular disease and a fixed PVR (or this may not have been established prior to pregnancy), they have the potential to develop it, and require very careful monitoring with serial echocardiograms.

Management

In the event of unplanned pregnancy, a therapeutic termination should be offered.3 Elective termination carries a 7% risk of mortality, hence the importance of avoiding pregnancy if possible.

If such advice is declined, multidisciplinary care, elective admission for bed rest, oxygen, and thromboprophylaxis are recommended. Therapies such as sildenafil and bosentan should be continued if they have led to reductions in pulmonary pressures, even though the latter is teratogenic in animals.

There is no evidence that abdominal or vaginal delivery or regional versus general anaesthesia improve outcome in pregnant women with pulmonary hypertension.

Marfan syndrome and pregnancy

Eighty per cent of Marfan patients have some cardiac involvement, most commonly mitral valve prolapse and regurgitation. Pregnancy increases the risk of aortic rupture or dissection, usually in the third trimester or early post-partum. Progressive aortic root dilation and an aortic root dimension > 4 cm are associated with increased risk (10%).1 Those with aortic roots > 4.6 cm should be advised to delay pregnancy until after aortic root repair.2 Conversely, in women with minimal cardiac involvement and an aortic root <4 cm, pregnancy outcome is usually good,2 although those with a family history of aortic dissection or sudden death are also at increased risk.

Valvular heart disease in pregnancy

Valvular heart disease affects ˜1% of pregnancies and may be associated with an increased risk of adverse maternal, fetal, and neonatal outcomes. High-risk features include:

left-sided valve stenoses1 (aortic stenosis (AS) with valve area <1.5 cm2 or mitral stenosis (MS) with valve area <2.0 cm2)

previous maternal cardiovascular system (CVS) event (congestive cardiac failure (CCF), transient ischaemic attack (TIA), cerebrovascular accidient (CVA)), or

Risk increases with each additive factor, see box opposite.

Classification of valvular heart disease risk in pregnancy

Low maternal and fetal risk