Global Pandemic of Heart Failure

Randall C. Starling

Overview

Congestive heart failure is an increasing, global epidemic, particularly in the elderly, that results in significant health care expenditure, disability, and mortality. Coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus are the major etiologic risk factors. Ironically, advances in the treatment of coronary artery disease and acute ischemic syndromes, which have saved lives, have resulted in a growing population of survivors with left ventricular dysfunction who are destined to develop the heart failure syndrome. Preventive measures that have evolved over the last 25 years, including hypertension management, have not reduced the incidence of heart failure. Congestive heart failure is the leading indication for hospitalization in the United States for patients older than 65 years. Most health care dollars spent on heart failure are for inpatient care. Heart failure is a chronic disease amenable to an intensive multidisciplinary care model (disease management program) designed to prevent hospital admissions through patient education, focused outpatient initiatives, and adherence to management guidelines that should enhance cost effectiveness and improve quality of life. Patients with advanced heart failure represent approximately 10% of the total heart failure population; they have the highest short-term mortality and consume the greatest percentage of resources (labor and dollars). Cardiovascular centers with expertise in the management of patients with advanced heart failure (through pharmacotherapy, circulatory support devices, surgical procedures, and heart transplantation) are necessary to deliver sophisticated care for this expanding population.

Congestive heart failure, traditionally considered an edematous disorder, was described hundreds of years ago. Hypertension and valvular heart disease were the most frequent comorbidities (1). Physicians could only attempt to control pulmonary and peripheral congestion with diuretic therapy. Heart failure was a progressive disease culminating in biventricular dysfunction, anasarca, and finally organ failure resulting from hypoperfusion. Today, symptomatic heart failure is most often characterized by effort intolerance (dyspnea) and fatigue without frank congestion. Thus, current guidelines refer to the condition as simply “heart failure.”

Heart failure is growing at epidemic proportions, particularly in the elderly. It consumes significant health care dollars and results in disability and premature death. Common illnesses, including coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus, are the major etiologic risk factors. In the United States, heart failure incidence is twice as common in hypertensive patients and five times greater in persons who have had a myocardial infarction (2). The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) estimates that 75% of patients with heart failure have antecedent hypertension. Major advances in the treatment of coronary artery disease and acute ischemic syndromes that have saved countless lives have resulted in a growing population of patients with chronic left ventricular dysfunction who may develop clinical heart failure. The NHLBI estimates that 22% of male and 46% of female myocardial infarction victims will develop heart failure within 6 years. Heart failure is the most common indication for hospitalization in the United States in patients more than 65 years of age. It is estimated that about one half of patients with heart failure are 65 years old or older. Finally, it is now recognized that the syndrome of heart failure may also occur as a consequence of diastolic dysfunction. Recent reports have shown that 40% to 50% of patients hospitalized with heart failure have normal ejection fractions.

The mainstay of heart failure therapy today is “treatment” for established and symptomatic disease. The public health impact of heart failure for our society will continue to grow until effective primary and secondary prevention strategies are adopted and employed. Recent heart failure guidelines now define patients at risk of heart failure (American College of Cardiology [ACC] stage A) as a high priority for preemptive therapy. Patients with advanced heart failure, ACC stage D, represent almost 10% of the total heart failure population, have the highest short-term mortality, and consume the greatest percentage of resources (3). The cost of treating advanced symptomatic heart failure is a growing economic burden for industrialized nations. An analysis of six countries revealed that 1% to 2% of total health care expenditures were for heart failure, and about 70% of the total heart failure cost was for hospital expenses (4). The rapidly increasing prevalence of heart failure clearly represents the most important public health problem in cardiovascular medicine (1,4,5).

Epidemiology

An epidemic is described as affecting or tending to affect a disproportionately large number of individuals within a

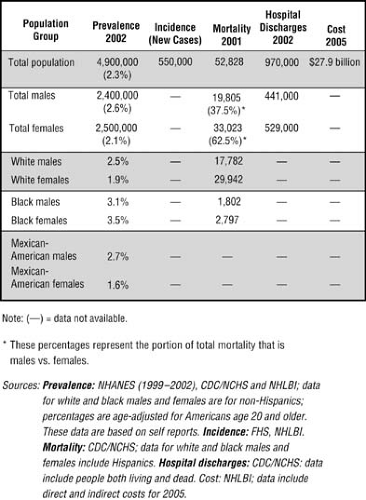

population, community, or region at the same time (excessively prevalent). Pandemic refers to a disease occurring over a wide geographic area and affecting an exceptionally high proportion of the population. Heart failure is a worldwide phenomenon that is indeed pandemic. Heart failure affects approximately 2 to 4 million U.S. residents and more than 15 million people worldwide (5) (Fig. 84.1). The American Heart Association estimates that there were 5 million U.S. residents alive in 2003 with congestive heart failure and 57,200 deaths (http://www.americanheart.org). Based on the 44-year follow-up of the NHLBI’s Framingham Health Study, heart failure incidence approaches 10 per 1,000 population after age 65 years. Despite declining mortality rates for cardiovascular disease in the United States, hospitalizations for heart failure have increased substantially. Hospital discharges for congestive heart failure in the United States rose from 399,000 in 1979 to 1,093,000 in 2003, a 174% increase (http://www.americanheart.org).

population, community, or region at the same time (excessively prevalent). Pandemic refers to a disease occurring over a wide geographic area and affecting an exceptionally high proportion of the population. Heart failure is a worldwide phenomenon that is indeed pandemic. Heart failure affects approximately 2 to 4 million U.S. residents and more than 15 million people worldwide (5) (Fig. 84.1). The American Heart Association estimates that there were 5 million U.S. residents alive in 2003 with congestive heart failure and 57,200 deaths (http://www.americanheart.org). Based on the 44-year follow-up of the NHLBI’s Framingham Health Study, heart failure incidence approaches 10 per 1,000 population after age 65 years. Despite declining mortality rates for cardiovascular disease in the United States, hospitalizations for heart failure have increased substantially. Hospital discharges for congestive heart failure in the United States rose from 399,000 in 1979 to 1,093,000 in 2003, a 174% increase (http://www.americanheart.org).

FIGURE 84.1. Heart failure statistics. CDC/NCHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NHLBI, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (From American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics: 2005 update. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association, 2005; http://www.americanheart.org) |

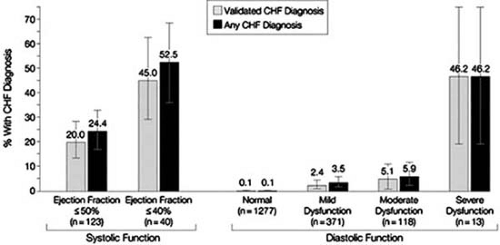

The criteria for the diagnosis of the syndrome of congestive heart failure are not standardized; hence population estimates may underestimate the extent of heart failure. Measures used in population-based studies and cardiovascular drug research rely on a composite of signs, symptoms, and diagnostic findings. Attempts to validate the Framingham clinical heart failure score against a measure of ejection fraction showed that, in patients with a low left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF <0.40), 20% met none of the criteria for congestive heart failure. A cohort of 2,000 persons aged 25 to 74 years living in Scotland underwent a detailed assessment of cardiac status including echocardiography (4). The overall prevalence of left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction 30%) was 2.9%; concurrent symptoms of heart failure were found in 1.5%, whereas the remaining 1.4% of study subjects were asymptomatic. Prevalence was greater with age and in men, reaching 6.4% in men aged 65 to 74 years. Population estimates of heart failure have many pitfalls, and utilization of death rates and hospitalizations likely grossly underestimates the true magnitude of the heart failure pandemic. An analysis using administrative data sets to create a definition of heart failure using diagnosis codes (REACH study) confirmed the heart failure epidemic in the United States (6). The authors concluded that ninth International Classification of Diseases–Clinical Modification codes and automated sources of data can be used within health systems to describe the epidemiology of heart failure. A population survey performed in Olmsted County, Minnesota by Redfield and coworkers provided further insights into the difficulty in truly measuring the prevalence of heart failure without sensitive techniques. Using detailed echocardiographic examinations and record reviews, the prevalence of validated congestive heart failure was 2.2%, with 44% having an ejection fraction greater than 50% (15). However, among those persons with moderate or severe diastolic or systolic dysfunction, fewer than half had recognized heart failure (Fig. 84.2), and, importantly, diastolic dysfunction, often unaccompanied by clinically recognized heart failure, was associated with marked increases in all-cause mortality. It can be concluded that the true incidence

and prevalence of heart failure are difficult to capture; however, most likely our current estimates are conservative and underestimate the true magnitude of the pandemic.

and prevalence of heart failure are difficult to capture; however, most likely our current estimates are conservative and underestimate the true magnitude of the pandemic.

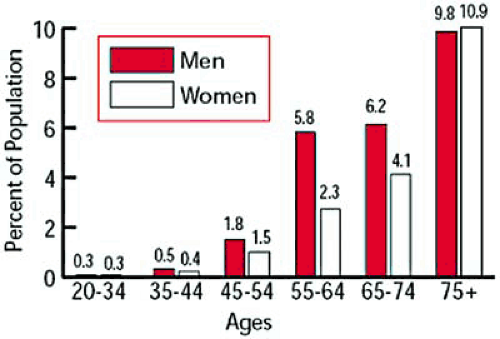

Incidence and Prevalence

Incidence refers to the number of new cases observed in a year in a defined population. Prevalence refers to the number of cases observed at a specified point in time in a defined population. The crude incidence of heart failure (unadjusted for age) ranges from 1 to 5 cases per 1,000 population per year and increases sharply with advancing age to as high as 40 cases per 1,000 population more than 75 years old (7). A reflection of the incidence of heart failure in the United States is made from the Framingham Study and the Framingham Offspring Study, representing a population of more than 10,000 (8). The prevalence of heart failure rises with age in both men and women, as shown in Figure 84.3.

A recent analysis of the Framingham Heart Study cohort demonstrated over the past 50 years that the incidence of heart failure has declined among women, but not among men; however, survival after the onset of heart failure has improved in both sexes (9). When established clinical criteria are used to define heart failure, the lifetime risk for heart failure is 1 in 5 for both men and women (10). Both hypertension and antecedent myocardial infarction significantly affect the lifetime risk for heart failure between ages 40 and 80 years in both men and women. These findings highlight the importance of risk factor modification to reduce ischemic heart disease and the potential impact of antihypertensive therapy to reduce the development of overt clinical heart failure. The incidence of heart failure is 550,000 cases per year in the United States. The annual rates per 1,000 population of new and recurrent heart failure events for nonblack men are 21.5 for ages 65 to 74 years, 43.3 for ages 75 to 84 years, and a striking 73.1 for age 85 years and older. For nonblack women in the same age groups, the rates are 11.2, 26.3, and 64.9, respectively. For black men, the rates are 21.1, 52.0, and 66.7, and for black women the rates are 18.9, 35.5, and 48.4, respectively (2).

Mortality

Since 1968, heart failure as the primary cause of death has increased fourfold (8). The most dismal prognosis for patients with severe symptoms (New York Heart Association class IV) and coronary artery disease was an 18% and 43% survival rate at 1 and 3 years, respectively (11). Symptomatic patients with dilated nonischemic cardiomyopathy who are receiving medical therapy have a better prognosis compared with patients with underlying coronary artery disease (11). Various risk factors influence mortality rates including age, renal dysfunction, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation.

Survival in patients with heart failure has improved over the past 50 years (Table 84.1). The 30-day, 1-year, and 5-year age-adjusted mortality among men declined from 12%, 30%, and 70% from 1950 through 1969 to 11%, 28%, and 59% in the period from 1990 through 1999. In women, the corresponding rates were 18%, 28%, and 57% for the period 1950 through 1969 and 10%, 24%, and 45% from 1990 through 1999 (9). Overall, there was an improvement in survival rate after the onset of heart failure of 12% per decade, a significant reduction in both men (p = .01) and women (p = .02). The explanation for this is purely speculative; however, the improved survival was temporally associated with the use of both angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and β-blockers. Another analysis examined the short- and long-term mortality of patients after initial hospitalizations for heart failure using a cohort of 38,702 consecutive patients from April 1994 through March 1997 in Ontario, Canada. The crude 30-day and 1-year mortality rates were 11.6% and 33.1%, respectively (12). Complex interactions among age, sex, and comorbidities affected short- and long-term survival. In the oldest comorbidity-laden subgroup, 30-day and 1-year mortality rates were 23.8% and 60.7%, respectively. A subgroup analysis from the Digitalis Investigation Group study showed that in ambulatory patients with congestive heart failure,

estimated creatinine clearance predicted all-cause mortality independently of established prognostic variables (13). In Cox regression analyses, independent predictors of mortality were estimated creatinine clearance, 6-minute walk distance of up to 262 m, ejection fraction, recent hospitalization for worsening heart failure, and need for diuretic treatment. It is obvious that, as a population ages, heart failure becomes more prevalent and the mortality rises, especially in patients with compromised renal function and comorbidities. It has been recognized that elderly persons have a substantial risk for death after a diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular systolic function. A longitudinal population-based study in 5,888 persons at least 65 years of age revealed that 4.9% had congestive heart failure, and the ejection fraction was normal in 63%, borderline decreased in 15%, or impaired in 22%, as determined by a core echocardiographic laboratory (14). Forty-five percent of those with heart failure and 16% without heart failure died within 6 to 7 years (14). A cross-sectional survey was performed in Olmsted County, Minnesota to determine the prevalence of diastolic and systolic dysfunction and to ascertain whether diastolic dysfunction was predictive of all-cause mortality (15). A cohort of 2,042 randomly selected residents of Olmsted County aged 45 years or older was surveyed between June 1997 and September 2000. The prevalence of heart failure was 2.2%, and 44% had an ejection fraction greater than 50%. Among those with moderate or severe diastolic or systolic dysfunction, fewer than 50% had recognized heart failure. Both mild and moderate or severe diastolic dysfunction were predictive of all-cause mortality as shown in Figure 84.4 (hazard ratio for severe diastolic dysfunction 10.17, p < .001).

estimated creatinine clearance predicted all-cause mortality independently of established prognostic variables (13). In Cox regression analyses, independent predictors of mortality were estimated creatinine clearance, 6-minute walk distance of up to 262 m, ejection fraction, recent hospitalization for worsening heart failure, and need for diuretic treatment. It is obvious that, as a population ages, heart failure becomes more prevalent and the mortality rises, especially in patients with compromised renal function and comorbidities. It has been recognized that elderly persons have a substantial risk for death after a diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular systolic function. A longitudinal population-based study in 5,888 persons at least 65 years of age revealed that 4.9% had congestive heart failure, and the ejection fraction was normal in 63%, borderline decreased in 15%, or impaired in 22%, as determined by a core echocardiographic laboratory (14). Forty-five percent of those with heart failure and 16% without heart failure died within 6 to 7 years (14). A cross-sectional survey was performed in Olmsted County, Minnesota to determine the prevalence of diastolic and systolic dysfunction and to ascertain whether diastolic dysfunction was predictive of all-cause mortality (15). A cohort of 2,042 randomly selected residents of Olmsted County aged 45 years or older was surveyed between June 1997 and September 2000. The prevalence of heart failure was 2.2%, and 44% had an ejection fraction greater than 50%. Among those with moderate or severe diastolic or systolic dysfunction, fewer than 50% had recognized heart failure. Both mild and moderate or severe diastolic dysfunction were predictive of all-cause mortality as shown in Figure 84.4 (hazard ratio for severe diastolic dysfunction 10.17, p < .001).

TABLE 84.1 Temporal Trends in Age-Adjusted Mortality after the Onset of Heart Failure: Men and Women ages 65 to 74 years (Percent; 95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|