7 Gender and Ethnicity Issues in Percutaneous Coronary Interventions

Introduction

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death regardless of gender and race.1 Until recently, information has been extrapolated from large studies and registries and has been applied to all population groups irrespective of gender, race, or ethnicity. However, there is a growing body of literature that has shown differences in cardiovascular disease manifestations and treatment effects, depending on gender and race. In this chapter, we will explore gender and racial differences in PCIs, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), acute coronary syndrome (ACS), stable angina, and adjunctive pharmacotherapy.

Gender

Gender

CVD is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity among women in the United States. It claims the lives of more women than the next five major causes of death in women combined.1 CVD in women occurs about 10 years later than in men, and in part, this has contributed to the misconception that cardiovascular disease is predominately a problem of the male gender. There has been much reported gender differences in outcomes between women and men, which may be explained by differences in comorbidities, pathophysiologic differences between genders, and disparities in treatment and outcomes following the cardiovascular event.1

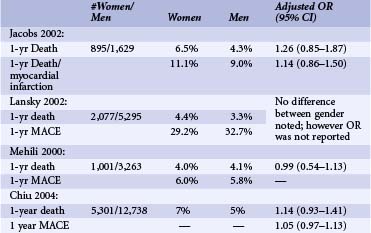

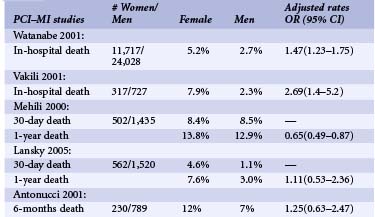

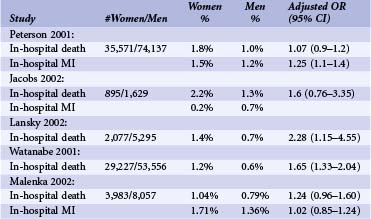

Percutaneous Coronary Interventions

More than 1.3 million PCIs are performed annually in the United States. An estimated 33% of PCIs are performed in women.1 Compared with men, women undergoing PCIs are 5 years older and have higher prevalences of hypertension, diabetes, and other comorbidities.2 They are less likely to have had a history of MI, PCIs, or coronary bypass graft surgery (CABG). At the time of PCIs, they have less multi-vessel disease and are more likely to present with unstable angina. Unlike men, they require more urgent procedures and are more likely to have rotational atherectomy. Compared with men, women have similar lesions types, less multi-vessel disease, and more preserved left ventricular (LV) function.2,3 However, paradoxically, despite better LV function, women tend to have higher incidences of congestive heart failure (CHF), and more functional impairment after revascularization than do men.4 Early reports of patients undergoing balloon angioplasty found lower procedural success rates in women. In addition, earlier registry studies showed that women had higher in-hospital mortality after PCIs even after adjusting for baseline comorbidites.5 However, recent studies report similar procedural success rates of 90% in both groups.3,5 Improved morbidity and mortality outcomes were observed in more recent studies despite older age and more complex lesion types (Tables 7-1 and 7-2).3,5 Table 7-1 shows the recently published data regarding in-hospital deaths and MI rates by gender. The table also includes large published studies since 2000, which reported odds ratios adjusted for age and risk factors. Even though there are variations in each of the studies, they show no differences in in-hospital mortality and morbidity rates. With newer-generation stents and balloons, smaller sheath sizes and catheters, and advances in adjunctive pharmacotherapies, adjusted long-term mortality and morbidity rates after PCI have become similar between men and women3,5–7 (see Table 7-2) (Fig. 7-1). There has been much controversy surrounding less frequent use of diagnostic catheterization and delays in PCIs in women compared with men.8 These issues will be addressed further in the section on ACS and MI later in the chapter.

TABLE 7-1 In-Hospital Death and Myocardial Infarction after Percutaneous Coronary Interventions by Gender

Gender and Devices

No gender-based comparisons were made in the earlier randomized clinical trials comparing bare metal stent (BMS) with balloon angioplasty. Re-stenosis and revascularization rates were not well defined for women after BMS because of the small sample of women in prospective trials with systematic angiographic follow-up. Even though women tend to have a smaller vessel size and a higher prevalence of diabetes, initially some intriguing studies reported that women had similar or lower target vessel revascularization (TVR) rates compared with their male counterparts after PCIs.9 However, systematic angiographic and clinical follow-up have not validated these studies. In the drug-eluting stent (DES) era, both sirolimus and taxus stents have shown favorable outcomes in women. Both the SIRIUS trial and the TAXUS IV trial have demonstrated the superiority of DES with reduction in re-stenosis, TVR, and major adverse cardiac events at 1-year follow-up in women and men.10,11 In TAXUS IV, 1314 patients with severe coronary artery stenosis were randomized to paclitaxel stent versus BMS. Women comprised 27.9% of the study population. Re-stenosis rates were similar in women and men treated with the TAXUS stent (7.6% vs. 8.6%, P = 0.80), as was late loss (0.23 mm vs. 0.22 mm, P = 0.90). Compared with BMS stents, women treated with the TAXUS stent had a significant reduction in 9-month re-stenosis (29.2% vs. 8.6%, P < 0.001) and 1-year target lesion revascularization rates (TLR) (14.9% vs. 7.6%, P = 0.02). Of note, women had higher unadjusted TLR rates compared with men at 1 year; however, female gender was not an independent predictor of TLR (OR 1.72, 95% CI 0.68–4.37, P = 0.25).12 A patient pooled analysis from four randomized sirolimus vs. BMS trials was done to assess for gender differences.13 In 1748 patients, of whom 497 were women, sirolimus-coated stents were associated with significant reduction in the rates of in-segment binary re-stenosis in women (6.3% vs. 43.8%) as well as in men (6.4% vs. 35.6%), which resulted in significant reduction in 1-year major adverse cardiac events (P < 0.0001). Few gender-based studies on the efficacy of directional atherectomy (DCA) exist. No gender-specific data on rotational atherectomy, cutting balloon angioplasty, extraction atherectomy, or gamma brachytherapy are available. DCA is no longer used, but from a historical perspective, it appears to be associated with lower procedural success and more bleeding complications in women.14 Likewise, large devices such as the Excimer laser angioplasty also are associated with higher morbidity rates in women with higher coronary perforation rates.14

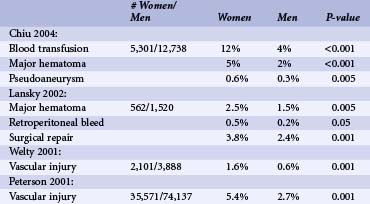

Vascular Complications

Women have experienced greater vascular complications such as major hematoma, retroperitoneal bleed, bleeding complications requiring transfusion, and vascular injury requiring surgery after PCI compared with men.7,15,16 Much of this is likely caused by smaller vessel size and aggressive anticoagulation. With the development of weight-adjusted heparin dosing, introduction of smaller sheath size, and early sheath removal, vascular complications have decreased.15,16 However, even in the current era, women continue to have 1.5 to 4 times higher risk of vascular complication compared with men.7,10,15,16 Table 7-3 shows different vascular complication rates by gender as reported in recently published large studies. Of note, there have been no gender-specific data on arterial vascular puncture closure devices. Since women have higher rates of vascular complications, they might be ideal candidates for radial access. Data are somewhat complicated.17

Gender Differences by Clinical Syndrome

Acute Coronary Syndrome

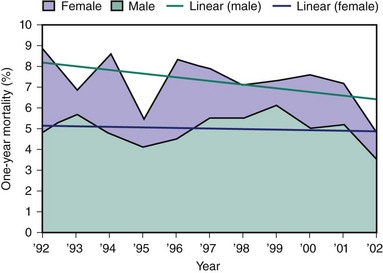

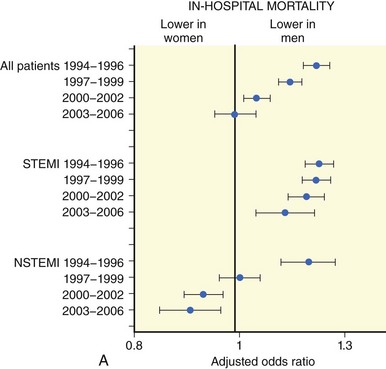

Women who present with ACS are older and have higher incidences of diabetes and hypertension compared with men. They also have less severe coronary artery disease, with greater absence of critical obstructions and more preserved left ventricular function. In ACS, women are more likely to have elevated cross-reactive (C-reactive) protein (CRP) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), whereas men are more likely to have elevated creatine kinase-MB and troponin.18 Randomized trials have shown the benefit of invasive strategy over conservative treatment in ACS; however, results in women have been confusing. A meta-analysis of eight large ACS trials, in which 3075 subjects were women and 7075 were men, has shed some insight into the confusion.19 These studies found that among ACS patients, as it was in men, an invasive strategy was safe and effective in women who had positive biomarkers when the composite endpoints of death, MI, or re-hospitalization (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.50–0.88) were reduced. However, in women with negative biomarkers, an invasive strategy did not reduce major adverse cardiac events and was associated with a trend toward higher rates for death or MI (OR 1.35; 95% CI 0.78–2.35).19 A recent study from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction in which 1.9 million patients were included showed that since 2000, women with NSTEMI had lower adjusted mortality than their male counterparts, which may be attributed to less obstructive CAD at the time of presentation in women (Fig. 7-2).28 Much has been reported on gender differences in the diagnosis and treatment of ACS, STEMI, and stable angina. Studies have shown delays in diagnosis and in health care–seeking behaviors as well as underutilization of cardiac catheterization and revascularization in women compared with men throughout the spectrum of CAD and treatment. In 2005, the CRUSADE investigators published their registry data on gender differences in patients with NSTEMI–ACS. In this large registry of over 35,000 patients, of which 41% were women, they found that women were less likely to receive guidelines-recommended therapy such as heparin (adjusted OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.86–0.97), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors I (ACE-I) (adjusted OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.90–0.99), and GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors (adjusted OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.81–0.92), compared with men, during acute hospitalization.20 Even troponin-positive patients were less likely to receive GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors (adjusted OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.81–0.92). Moreover, women were less likely to undergo diagnostic catheterization (adjusted OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.82–0.91) or PCI (adjusted OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.86–0.96) during hospitalization.20 Women were less likely to receive guidelines-recommended medical therapies such as aspirin (adjusted OR 0.91 95% CI 0.85–0.98), ACE-I (adjusted OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.88–0.98), and statin (adjusted OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.88–0.98) at the time of discharge. The CRUSADE registry confirms the unfortunate presence of continued treatment disparities between the groups. Another published study using the ACC-NCDR (American College of Cardiology–National cardiovascular data registry) registry regarding gender differences among patients with ACS both NSTEMI and STEMI again showed gender disparities in treatment.21 Of 199,690 patients, the 55,691 women, in spite of having fewer high-risk criteria, had higher rates of in-hospital complications. For example, although the adjusted mortality among women and men was similar (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.88–1.07, P = 0.52), women had higher rates of complications such as CHF (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.69–0.92, P = 0.002), bleeding complications (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.52–0.58, P < 0.01), and cardiogenic shock (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.75–0.89, P < 0.01). Moreover, they found that women were less likely to receive aspirin (OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.13–1.20, P < 0.01) or GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.08–1/13, P < 0.01) at admission and were less likely to be discharged on statins (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.07–1.13, P < 0.01) or aspirin (PR 1.17, 95% CI 1.13–1.21, P < 0.01). These findings call for significant improvements in the care of ACS patients and highlight the importance of continued investigations into barriers that contribute to these differences.

Figure 7-2 In-hospital mortality rates for women and men.

(Reprinted with permission from Rogers WJ, Frederick PD, Stoehr E, et al: Trends in presenting characteristics and hospital mortality among patients with ST elevation and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am Heart J 2008;156:1026–1034.)

ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction

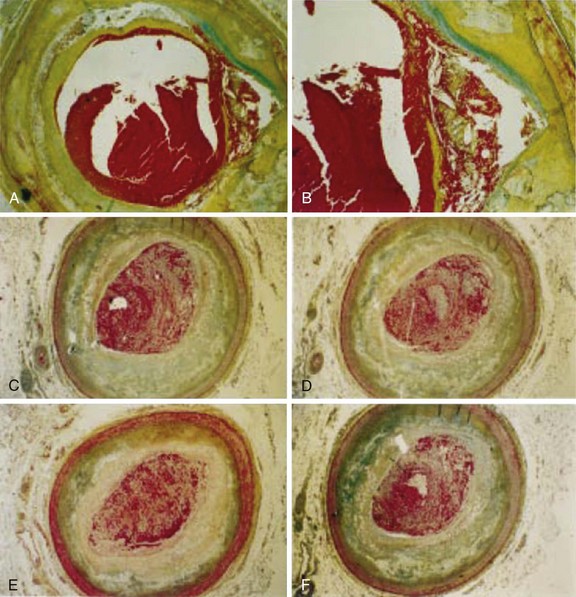

Women with MI are older and have more comorbidities compared with their male counterparts. Moreover, they are likely to present to hospital later than men with a higher Killip class. At the time of presentation, women have less severe CAD and more preserved left ventricular function. In the majority of cases, the initial presentation of CAD in women is sudden cardiac death (SCD) or acute MI. Surprisingly, there appear to be differences in plaque morphology between women and men with acute MI. Autopsy studies have shown more plaque erosion than plaque rupture in young women after fatal MI compared with men or older women (Fig. 7-3, A and B).22 Also, women appear to have more distal microvascular embolization compared with men during fatal MI.23 The overall superiority of primary PCI over fibrinolytic therapy for women has been demonstrated.24 Because of more comorbidities in women at presentation, the absolute benefit with primary PCI is greater for women than for men. An estimated 56 deaths could be prevented for every 1000 women treated with primary PCI compared with 42 fewer deaths per 1000 men.24 A study has shown that there are gender-associated differences in the amount of myocardial salvage after primary PCI for STEMI. In this study, myocardial salvage achieved by primary PCI was greater in women than in men.25 Improved salvage may be attributed to gender-specific hypoxic tolerance. Female cells have a higher baseline expression of the protein Bcl-2, showing a higher inherited hypoxic tolerance than male cells.25

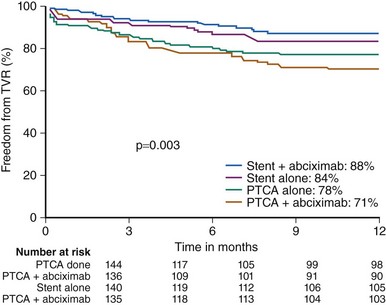

Gender-specific data regarding primary stenting versus primary balloon angioplasty in STEMI have been available. Women with STEMI benefitted from primary stenting with less re-infarction, TVR, and TLR. The CADILLAC trial which enrolled 2082 patients, of which 27% were women, to BMS versus primary balloon angioplasty with or without GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor, found superior efficacy and safety with primary stenting with or without abciximab compared with balloon angioplasty (Fig. 7-4).10 In women, primary stenting resulted in a reduction in the 1-year composite of death, re-infarction, ischemia-driven TVR, or disabling stroke from 28.1% to 19.1% (P = 0.01) compared with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA).10 The addition of abciximab to primary stenting significantly reduced the 30-day ischemic TVR without increasing bleeding or stroke rates for women.14 Much controversy has surrounded mortality rate differences between women and men after STEMI (see Table 7-4). There appears to be higher in-hospital mortality rates among women undergoing PCI for STEMI compared with men. A large study using Nationwide Inpatient Sample of 11,717 women and 24,028 men found a 5.2% in-hospital mortality rate in women compared with a 2.7% mortality rate in men. Even after adjusting for age, hypertension, institutional volume, and pulmonary disease, women had higher mortality rate (OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.23–1.75).26 Similarly, the New York State Department of Health database found that women had significantly higher adjusted in-hospital mortality rate (OR 2.69 95% CI 1.4–5.2).27 The recently published data from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction showed that women with STEMI have higher in-hospital mortality rates compared with men (see Fig. 7-2).28 However, by 30 days and 1 year, there appears to be no difference in mortality rates between the two groups (see Table 7-4). Of note, female gender is an independent risk factor for the development of cardiogenic shock as a complication of acute MI. However, there is no gender difference in the mortality rates of cardiogenic shock once age is adjusted. Thus, the ACC/AHA guidelines for the treatment of STEMI recommend PCI or CABG for patients age <75 years who are in cardiogenic shock and have lesions amenable to revascularization, regardless of gender.4 Many studies have shown delay in time to treatment, time to invasive diagnostic test, and time to revascularization in women. Women with STEMI are less likely to undergo primary angioplasty within 2 hours or have accepted pharmacologic treatment on admission. Even at discharge, women are less likely to be on accepted medical treatment.29 The older age of the female patients, the symptom differences, and the delay in presentation after AMI have been suggested as possible explanations. While these factors may explain initial treatment differences, it does not explain the treatment disparities once the diagnosis has been made. Continued quality improvement in the diagnosis and treatment of women with CAD are needed.

Figure 7-4 Target vessel revascularization rate in women enrolled in the CADILLAC trial.

(Reproduced with permission from Lansky et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention and adjunctive pharmacotherapy in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2005;111(7):940–953.)