Percutaneous catheter ablation is a safe and effective treatment for symptomatic drug-resistant atrial fibrillation (AF). Gastroparesis is a little known complication of AF ablation. We aimed to evaluate the frequency of gastroparesis in the patients who underwent catheter ablation for AF by cryoballoon (CB) or radiofrequency (RF) and to define risk factors for gastroparesis. In all, 104 patients were treated with pulmonary vein (PV) isolation with 2 different technologies: CB in 58 patients (group 1) and open-irrigated tip RF catheter in 46 patients (group 2). Gastroparesis was seen in 7 cases (6 cases in group 1 and 1 case in group 2, respectively). The complaints related with gastroparesis began during the procedure in 4 of 6 patients of group 1. The other 3 patients admitted to our outpatient clinic with similar complaints within 72 to 96 hours after the procedure. For gastroparesis cases of group 1, mean minimal CB temperature on inferior PVs was lower and left atrium diameter was smaller. Management was conservative, and the patients have no residual symptoms at 6-month follow-up. The only patient still demonstrating residual symptoms during follow-up was in group 2. Although, clinically manifest gastroparesis is quite common with CB ablation, the process is generally reversible. However, damage may not be as reversible with RF ablation. In conclusion, during cryoablation, lower temperatures on inferior PVs and small left atrium size may be associated with increased risk of gastroparesis, and fluoroscopic guidance may be useful to avoid this complication.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, with an estimated prevalence of 1% to 3%. The pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) still remains the cornerstone of AF ablation procedures. Cryoballoon (CB) ablation and radiofrequency (RF) catheter ablation have become effective and widely accepted tools for PVI. Gastroparesis is a syndrome characterized by delayed gastric emptying in absence of mechanical obstruction of the stomach. The disorder is associated with symptoms such as epigastric discomfort, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and bloating. It is postulated that gastroparesis associated with AF ablation may be caused by periesophageal vagal nerve injury, and it was reported as a complication of RF catheter ablation in the patients with AF. However, the frequency and the risk factors of gastroparesis as a complication of CB ablation were not clearly elucidated in the literature. The main objectives of this study were to define the factors associated with the occurrence of gastroparesis in PVI procedures using cryoenergy or RF energy.

Methods

Consecutive patients with symptomatic, drug-refractory paroxysmal, or persistent AF who underwent PVI were included in this prospective study. Patients were classified as having paroxysmal or persistent AF according to the current guidelines. Patients underwent PVI with either CB catheter (58 patients, group 1) or with conventional open-irrigated tip RF catheter (46 patients, group 2) randomly.

Exclusion criteria were intracardiac thrombi documented by transesophageal echocardiography, severe systolic heart failure (left ventricular ejection fraction <30%, left atrial size >55 mm), New York Heart Association class IV, long-standing persistent AF, previous AF ablation procedure, previous abdominal surgical procedures, history of either acute or chronic neuropathies, use of drugs that affect gastrointestinal motility, inadequate follow-up, anticoagulation, and/or inability to provide informed consent. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the procedure. The local ethical committee approved the study. All antiarrhythmic drugs were discontinued 5 half-lives before the procedure. All procedures were performed under minimal sedation with midazolam.

A single or double transseptal puncture was performed according to the use of a conventional circumferential mapping catheter (Inquiry Optima PLUS Catheter; St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN) or the customized mapping catheter (Achieve; Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota) in both groups. For group 1, positioning of the second-generation 28-mm CB catheter (Arctic Front Advance; Medtronic) was achieved using the guidewire and the 12Fr-steerable sheath (Flexcath; Medtronic). Although delivering cryoenergy to right pulmonary veins (PVs), a 6F decapolar coronary sinus catheter or a quadripolar diagnostic catheter were positioned in the superior vena cava for phrenic nerve stimulation. Before each freeze, grade of occlusion (semiquantitative scale from 1 [poor occlusion] to 4 [perfect occlusion]) was quantified with an injection of contrast medium. After confirmation of PV occlusion by contrast injection, the 240-second freezing cycle was initiated. After 2 freezing cycles, PVI was assessed by circumferential mapping catheter. Isolation of PVs were defined as the presence of both entrance and exit block. For group 2, an open-irrigated tip catheter with a 3.5-mm-tip electrode (ThermoCool; Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, CA) was used in conjunction with a 3-dimensional electroanatomic mapping system (Ensite, NavX Fusion, St. Jude Medical). RF energy was delivered with power of up to 35 W and a maximum temperature of 43°C. Ablation was performed circumferentially, guided by a conventional circular mapping catheter, near the antrum of each PV. The esophageal probe was not used to monitor temperature in the RF group. Instead, RF power was limited to 20 to 25 W on the posterior wall. For the patients with paroxysmal AF, the electrophysiological end point was the achievement of a bidirectional conduction block between the left atrium (LA) and PVs. We used the creation of complete continuous circumferential lesions around the ipsilateral veins as an anatomical end point in the patients with persistent AF.

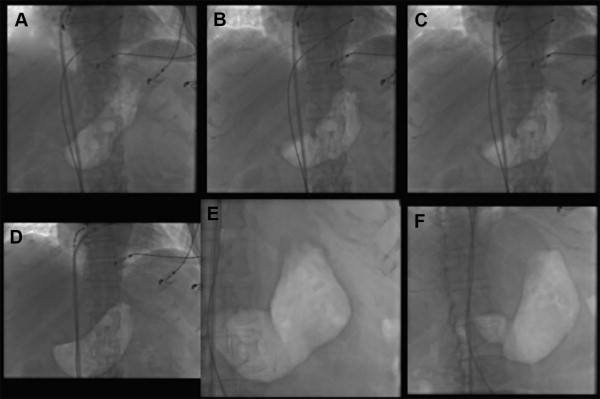

During the procedure, gastroparesis was suspected in the present of following symptoms: epigastric discomfort, abdominal pain, heartburn, bloating, nausea, or vomiting, and all symptomatic patients were prospectively evaluated by fluoroscopy for an air-filled stomach or air fluid level in the fundus of an enlarged fluid-filled stomach ( Figure 1 ). The patients showing an air-filled stomach or air fluid level in the fundus of an enlarged fluid-filled stomach on fluoroscopy were evaluated by gastric emptying scintigraphy (GES) to confirm the diagnosis. After the procedure, all patients were comprehensively questioned for the following symptoms: acute onset of characteristic prolonged symptoms of gastric delayed emptying, such as nausea, vomiting, postprandial fullness, bloating, constipation, or epigastric pain. All symptomatic patients were prospectively investigated for gastroparesis and underwent abdominal x-ray to evaluate the findings of gastric hypomotility. The patients showing gastric hypomotility findings on abdominal x-ray were evaluated by GES to confirm the diagnosis. Patient identification number (PIN) was given for the patients in whom the diagnosis of gastroparesis was confirmed by GES. The scintigraphical evaluations were performed as previously described. Standard imaging of the gastric area with the patient standing is performed at baseline and at 1 and 4 hours after meal ingestion. Gastric emptying is considered delayed if there is >60% retention at 2 hours or 10% retention at 4 hours.

All patients were followed up for at least 12 hours in coronary intensive care unit. Patients were then discharged provided that their clinical statuses were stable. Oral anticoagulation was initiated in the evening of ablation unless pericardial effusion was detected and continued for at least 3 months after the procedure. Antiarrhythmic drug treatment was also continued for at least 3 months. Regular follow-up consisted of outpatient clinic visits at 1, 3, and 6 months after the procedure and included a detailed history for arrhythmia or gastroparesis-related symptoms, physical examination, 12-lead ECG, and 24-hour Holter monitoring. In patients having gastroparesis-related symptoms, GES was performed to define the prognosis of disease at 1 and 6 months.

SPSS 17.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York) was used for statistical analysis. All the quantitative variables with a normal distribution were reported as mean ± SD and compared using the Student’s t test. For values with non-normal distribution, comparison was performed with Mann-Whitney U test. For the descriptive variables comparison, the Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used, when appropriate. The independent association of clinical variables with gastroparesis was assessed using multivariable linear regression. Receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis was performed on significant predictors to calculate the accuracy and other diagnostic parameters and to determine a cutoff point at the maximum sum of sensitivity and specificity. p Value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The study population consisted of 104 consecutive patients (mean age 58 ± 12 years, 51% women) from February 2012 to August 2014. The baseline characteristics of the patients did not differ among groups ( Table 1 ). In group 1, the procedural end point of complete PVI was achieved in all 58 patients. A left-sided common ostium was seen in 3 patients. Mean cryoenergy delivery duration was 36 ± 4.0 minutes with a mean of 9.3 ± 1.4 applications ( Table 2 ). Of 232 PVs, 230 (99%) were isolated using CB ablation alone and the other 2 PVs were isolated using additional 3.5-mm irrigated tip RF ablation catheter. In group 2, all PVs were successfully isolated with a mean of 45 ± 21 pulses with RF and mean energy delivery duration of 35 ± 12 minutes.

| Variables | All patients n=104 | Group 1 n=58 | Group 2 n=46 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57±12 | 55±12 | 59±10 | 0.145 |

| Female | 53 (51%) | 29 (50%) | 24 (52%) | 0.663 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m 2 ) | 25±3.7 | 25±3.9 | 25±3.9 | 0.881 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 19 (18%) | 10 (17%) | 9 (20%) | 0.763 |

| Hypertension | 48 (46%) | 25 (43%) | 23 (50%) | 0.337 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 15 (14%) | 8 (13%) | 7 (15%) | 0.774 |

| Smoker | 44 (45%) | 24 (41%) | 20 (43%) | 0.792 |

| Duration of AF (years) | 3.2±2.7 | 3.9±2.6 | 4.5±2.8 | 0.304 |

| Persistent AF | 14 (13%) | —- | 14 (30%) | —- |

| LA diameter (mm) | 42±4.9 | 41±4.5 | 44±5.0 | 0.025 |

| LVEF (%) | 58±5.8 | 59±4.9 | 57±6.5 | 0.549 |

| CHA 2 DS 2 -VASC score | 1.4±1.2 | 1.4±1.2 | 1.3±1.2 | 0.812 |

| EHRA score | 2.5±0.6 | 2.5±0.6 | 2.4±0.54 | 0.781 |

| Variable | Total (n=58) | Gastroparesis (-) (n=52) | Gastroparesis (+) (n=6) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal Temperature (C°) | LSPV | -49±2.4 | -49±2.5 | -50±2.0 | 0.430 |

| LIPV | -48±3.9 | -47±2.7 | -55±4.8 | <0.0001 | |

| RSPV | -51±3.1 | -51±3.2 | -50±1.0 | 0.324 | |

| RIPV | -45±3.6 | -45±3.3 | -50±1.5 | <0.0001 | |

| Occlusion Grade | LSPV | 3.8±0.3 | 3.7±0.3 | 3.4±0.5 | 0.740 |

| LIPV | 3.7±0.4 | 3.8±0.3 | 3.2±0.4 | 0.610 | |

| RSPV | 3.9±0.1 | 3.9±0.1 | 3.9±0.1 | 0.410 | |

| RIPV | 3.8±0.3 | 3.8±0.3 | 3.7±0.4 | 0.140 | |

| Freezing Duration (minutes) | LSPV | 8.4±1.4 | 8.4±1.4 | 8.5±0.9 | 0.760 |

| LIPV | 8.7±1.7 | 8.8±1.8 | 8.4±1.1 | 0.600 | |

| RSPV | 8.2±0.8 | 8.2±0.7 | 8.8±0.8 | 0.420 | |

| RIPV | 10±3.3 | 9.9±3.2 | 12±3.8 | 0.140 | |

| Number of Application | LSPV | 2.1±0.4 | 2.1±0.4 | 2.2±0.4 | 0.460 |

| LIPV | 2.2±0.6 | 2.3±0.6 | 2.1±0.3 | 0.530 | |

| RSPV | 2.0±0.2 | 2.0±0.3 | 2.5±0.3 | 0.390 | |

| RIPV | 2.8±1.2 | 2.7±1.2 | 3.2±1.2 | 0.270 |

Table 3 summarized baseline characteristic and procedural features of the patients with gastroparesis. Fluoroscopy showed enlarged air-filled stomach in all patients with gastroparesis. In group 1, a total of 6 patients (10%) were diagnosed as gastroparesis. In 4 of 6 patients (PIN 1 to 4; 6.8%), the symptoms emerged during the procedure. The other 2 patients (PIN 5 and 6) were admitted our outpatient clinic in the first 96 hours after ablation. The procedure time and energy delivery duration were comparable for the patients with and without gastroparesis. However, mean minimal temperature on inferior PVs was lower and the diameter of LA was smaller in the patients with gastroparesis than without ( Table 2 ).