10

Fungal Diseases, Including Pneumocystis

Fungi are ubiquitously distributed in nature, and fungal diseases, in both animals and humans, are found in all climates throughout the world. Fungi are eukaryotic and have no chlorophyll. In tissue, fungi typically appear as round to oval unicellular yeasts, sometimes with one or more buds, or as segmented or nonsegmented filamentous forms. A single filament is a hypha (pl. hyphae), and a mass of these filaments forms a mycelium (pl. mycelia). If a bud of a yeast remains attached and continuously buds and elongates, a pseudohypha is produced. Pseudohyphae have bulging, nonparallel sides and constriction at the septa, whereas true hyphae have parallel walls.

Fungi that grow in a mycelial form at 25°C and as yeasts at 37°C are referred to as dimorphic. Asexual reproduction in hyphae occurs either by the formation of a sporangium or “fruiting head,” a closed structure in which asexual spores (sporangiospores) develop, or by the development of modified hyphae called conidiophores, which produce asexual spores called conidia. The majority of yeasts reproduce asexually by budding. In some fungi the body (or thallus) of a fungus (i.e., the mass of intertwined hyphae) produces sexual spores; the fungi in which this sexual reproduction occurs are known as perfect fungi. Fungi that lack a known perfect (sexual) state are the more common respiratory pathogens but exclude the Phycomycetes, Histoplasma capsulatum, and Coccidioides immitis.

This chapter discusses the common fungal pathogens in immunocompetent patients (the so-called deep mycoses of histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, and coccidioidomycosis) as well as those fungi generally considered saprophytes in nature but that may become pathogenic in the immunocompromised host. Pneumocystis carinii (jiroveci) is now included among fungi. Bronchocentric granulomatosis, a histologic pattern that may be seen as a response to fungal or other infections or may exist in an idiopathic form, is discussed under Aspergillus sp. Several general references on pulmonary fungal diseases are available.1–5

Aspergillosis

The Aspergillus sp. are a group of saprophytic fungi that are ubiquitous in nature. Of the more than 100 known species of Aspergillus, fewer than 20 are pathogenic to humans, the most common being Aspergillus fumigatus.6,7 The fungus may be recovered in large numbers from such sites as compost piles, haystacks, fertile soil, standing water, and ambient air, which is apparent if one leaves an appropriate culture medium, such as a piece of fruit or bread, exposed in one’s kitchen. A. niger, A. terreus, A. flavus, A. ochraceus, A. nidulans, and A. clavatus have been reported to cause disease.8–16 However, it has been estimated that 90% of human infections are due to A. fumigatus.

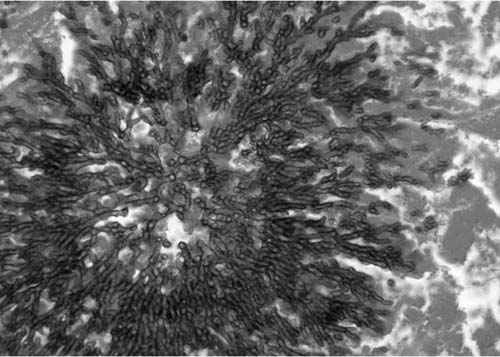

The appearance of the fungus in human tissues is usually as individual fungal hyphae or as a mass of hyphae, a mycelium. The hyphae are 3 to 6 μm in diameter, averaging 4 μm, and are segmented with dichotomous branching at ~45 angles, as seen in Fig. 10–1. In a growing mycelium, individual hyphae often align themselves in parallel fashion. The various species of Aspergillus appear mostly identical in tissue, and all pathogenic species can produce the kinds of diseases described next.

FIGURE 10–1 A mass of Aspergillus species hyphae growing in necrotic lung. Note sunburst arrangement and 45-degree angle branching [Gomori’s methenamine silver (GMS) × 240].

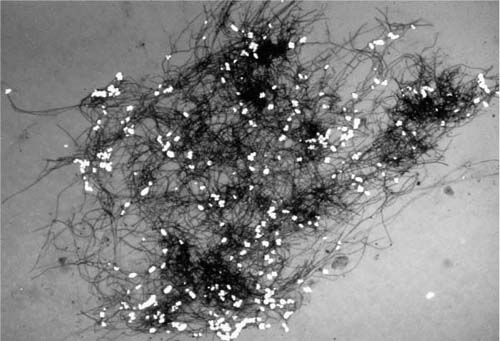

One exception to the inability to distinguish various Aspergillus sp. mycelia is A. niger. This fungus often produces calcium oxalate, the crystals of which are easily seen associated with the fungus by using crossed polarizing light.9,10 Fig. 10–2 shows a bronchial washing with A. niger and oxalate crystals. Occasionally, on the surface of abscess walls or the bronchial mucosa or rarely on the pleural surface, the mycelia give rise to conidia borne on conidiophores. If conidia are present, their morphology is helpful in identifying the specific species of Aspergillus.1 Not every positive microbiologic culture for Aspergillus sp. means infection, because the organism is a common contaminant of cultures and may be recovered from such respiratory specimens such as sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid in patients without aspergillus infection. The clinical setting often clarifies the possible pathogenicity of aspergillus recovered in culture. Sometimes a biopsy may be needed to document the invasiveness of the organism and thus prove that it is causing disease. The commonly recognized forms of Aspergillus infection are (1) aspergilloma, or Aspergillus fungus ball; (2) allergic (hypersensitivity) bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; (3) acute invasive Aspergillus pneumonia; (4) Aspergillus bronchitis; and (5) chronic cavitary aspergillosis. An older classification had regarded Aspergillus infection as saprophytic, allergic, or invasive, and an additional category of semiinvasive infection was added.17–19 The classification just given has added bronchial disease from Aspergillus sp. as a specific form of invasive aspergillosis.

FIGURE 10–2 Aspergillus niger with calcium oxalate crystals in a bronchoalveolar lavage (Pap stain, polarized light, ×60).

Aspergilloma

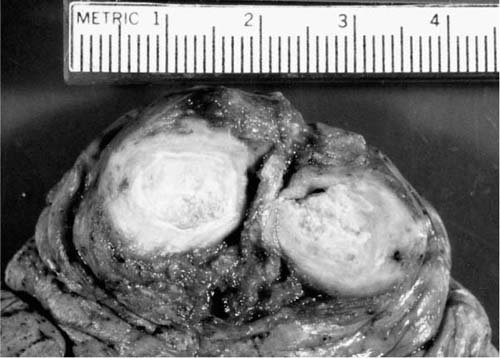

An aspergilloma is a mass of Aspergillus sp. mycelia that accumulates in a preexisting lung cavity, as seen in Fig. 10–3. Aspergilloma accounts for approximately two thirds of cases of pulmonary aspergillosis. Diseases that commonly give rise to cavities that may become colonized with Aspergillus sp. are tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, bronchiectasis, bullae, and old abscesses.20–22 Typically, the lining of such an infected cavity consists of mixed chronic inflammation with fibrosis and perhaps squamous metaplasia. The organism is typically not invasive but is freely movable as a mass within the cavity, as may be demonstrated radiographically. Grossly, the fungus ball is a filamentous aggregate of soft, dull gray to tan material. Microscopically, the tangle of hyphae is such that the details of separation and branching are seen best at the edges. Most of the mycelium is eosinophilic, as the organisms are largely dead. Aspergillomas occur more frequently in the upper lobes of the lungs and may cause hemoptysis. Resection of aspergillomas for hemoptysis may be necessary, but such surgery is often difficult because of the large amount of fibrous pleural adhesions surrounding the affected portion of lung.23,24 Occasional cases of limited tissue invasion in aspergilloma have been seen.21

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is an allergic reaction to aspergillus and occasionally other fungi and thus differs in pathogenesis, clinical and pathologic manifestations, and treatment from most fungi in the lung that represent true infectious processes.

The occurrence of tenacious mucoid plugs of the lobar, segmental, and more distal airways, typically in the upper lobes, has been described since the time of Galen; an expectorated mucous plug was illustrated by John Hunter in the 1800s.25 Often, patients with such a condition seek medical attention because of expectoration of these rubbery, branching mucous plugs. Such mucous plugging has been referred to as “plastic bronchitis,” or, more commonly, “mucoid impaction of bronchi.”26–28 The former term is used more frequently in reference to patients with airway disease expectorating mucous plugs, whereas the latter more specifically refers to asthmatic (occasionally chronic bronchitic) patients presenting with complaints referable to bronchial mucous plugging. However, there is no real clinical or histologic distinction between the terms.25 In such patients, the bronchial walls are dilated but still retain the usual tissue components. The changes of asthma (i.e., thickened basement membrane, infiltrates of eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells, and hypertrophy/hyperplasia of mucous glands and smooth muscle) are seen in many of these cases. In the other cases, changes of chronic bronchitis or cystic fibrosis are evident. A few patients have no evident underlying disease.25

FIGURE 10–3 Gross appearance of a fungus ball (mycetoma).

Some patients with mucous plugging of bronchi, usually those with clinical asthma, become symptomatic with nonspecific respiratory complaints such as cough, fever, and wheeze. Mucoid plugs in airways produce a characteristic radiologic image, one of branching densities radiating from the hilum.29–31

The airways of patients with such bronchial mucous plugging are often colonized with Aspergillus fumigatus, which proliferates in the bronchial mucus and produce an inflammatory response, though rarely is there evidence of tissue invasion.32 This is the ABPA entity defined earlier.17,25,29–31,33–37 Proximal bronchi show the changes of asthma, and small numbers of Aspergillus fumigatus hyphae can be seen in the bronchial mucus, often only with the use of appropriate histochemical stains for fungi.38,39 Proximal bronchial mucous plugging is shown in Fig. 10–4. The mucus often stains particularly basophilic because it is dehydrated and of high protein content.40 Desquamated epithelium, neutrophils, and macrophages may be seen in the mucus, but the most striking cellular elements are large numbers of dead, shrunken (some would say mummified) eosinophils. Because they often are degenerated or clumped together, a stain for eosinophil granules, such as a tissue Giemsa stain, may help to identify them.40 The bronchial mucous plugs are particularly rubbery and have occasionally been coughed up to form a cast of the affected airways. Culture and fungal stains on this material may confirm the clinical suspicion of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in a patient expectorating such plugs. Infrequently, another species of Aspergillus or another fungus produces the same clinical and histologic disease, promoting use of the term allergic bronchopulmonary fungal disease.41–43 A review article summarizes the various fungi that have been reported to produce allergic bronchopulmonary fungal disease.42 The bronchial lesions may progress to bronchiectasis (i.e., fixed dilatation of the airways rather than simple dilatation due to the mucus) if the underlying hypersensitivity response does not remit. On the other hand, lesions of ABPA may spontaneously clear and usually are quite responsive to corticosteroid therapy, which ameliorates the underlying immune response.33–37

Distal airways may show more severe inflammation and conversion of the bronchial wall to resemble the wall of a necrotizing granuloma. The normal elements of the wall of the airway are replaced by palisading histiocytes and giant cells; eosinophils, mucus, and cellular debris are found in the middle of the airway. This histologic picture is called bronchocentric granulomatosis (see next section).25,44–46 Elsewhere in the lung of patients with asthma and hypersensitivity on an immune complex (type III) or cellular (type IV) basis, parenchyma develop small noncaseating granulomas, as seen in other kinds of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Eosinophilic or obstructive (endogenous lipid) pneumonia may also be present.25

FIGURE 10–4 Dilated large bronchi distended by tenacious mucus in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.

Bronchocentric Granulomatosis

The gross and histological appearance called bronchocentric granulomatosis (BCG) can be seen in other fungal diseases as well as a spectrum of other infectious and noninfectious diseases.47–54 Those entities are reviewed here. In 1973, Dr. Averill Liebow described a pattern of chronic lung injury consisting of airway-centered necrotizing granulomas; the necrotic center of the lesions lay within the lumina of small to medium-size airways, and the airway walls were replaced by palisading histiocytes, lymphocytes, and giant cells. He termed this histologic picture bronchocentric granulomatosis and contrasted its airway-based appearance with the vascular-based or angiocentric lesions of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Subsequent articles described BCG with and without asthma; the nonasthmatics did not have tissue eosinophilia and often had no fungi or other infectious agents in the lesions.45,46 Thus, an idiopathic form of BCG was recognized. With time, it has been realized that bronchocentric granulomatosis is not a specific disease but a pattern of inflammatory response to quite a large number of fungi and mycobacteria.47–52 Similar lesions of small airways have also been linked to rheumatoid arthritis.53,54

Grossly, the lesions are distinctive because the airways are filled with mucoid or granular yellow material. A gray-tan zone of infiltrate may be seen around this central material. When part of ABPA, several branches of airways may be involved. Histologically, at low power the lesion resembles a necrotizing granuloma, with the adjacent artery next to the lesion indicating that the lesion is based on an airway. Sometimes the side of the artery closer to airway shows lymphocytic infiltrate, but often the vessel is normal. The bronchial wall is replaced by multinucleate giant cells, palisading histiocytes, and mixed chronic inflammation. If the lesion is in an asthmatic and associated with fungi, often Aspergillus sp., eosinophils may be abundant, especially in the central necrotic material. All cases of BCG should be searched thoroughly for organisms before being considered “idiopathic.” Because such fungi as H. capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis, and C. immitis can produce this histologic picture, as well as typical and atypical mycobacteria and echinococcal infection, one should treat the lesion like any other necrotizing granuloma of unknown cause. The association with rheumatoid arthritis is interesting, as BCG lesions may have the appearance of rheumatoid nodules centered on airways. In most cases, the lesions respond well to corticosteroid therapy or do not recur after surgical excision. In a minority of cases, the lesions have cleared spontaneously.

Invasive Aspergillus Pneumonia

Lung parenchymal invasion by Aspergillus sp. is seen in the immunocompromised host, particularly in patients during treatment for hematologic disorders following heart, lung, liver, renal, or bone marrow transplantation, or as a complication of AIDS.6–8,12,55–68 Neutropenia appears to correlate with the occurrence of the lesions, rather than corticosteroid or cyclosporine therapy.57,61,69 Occasional cases have also been described in nonimmunosuppressed individuals. Fever, dyspnea, nonproductive cough, and occasionally hemoptysis are typical clinical symptoms. The pulmonary infiltrates may be single or multiple and tend to be enlarging, rounded infiltrates, often involving a large portion of the lung. The fungus then infiltrates through the wall into the adjacent pulmonary artery, producing thrombosis and infarction. As the fungi then proliferate rapidly through the hemorrhagic and infracted lung, particularly though the vasculature, they produce a rounded, expanding infarct rather than the classic wedge-shaped, pleural-based noninfected infarct.6,49 Radiologic imaging, particularly computed tomography, captures the development of these changes well and can strongly suggest the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis, as well as recognize lesions before they are symptomatic.59 BAL can assist in diagnosis, but transbronchial lung biopsy may be necessary to demonstrate tissue invasion by the fungus.66,67 Treatment of such infections is occasionally successful, and the infarcted lung may form a chronic cavity with the dead Aspergillus sp. mass in the middle forming a fungus ball or aspergilloma.8,21

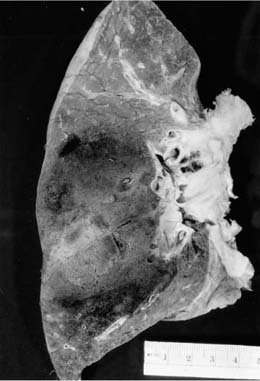

Grossly, the involved lung has the appearance of an infarct, being dark red and very firm, often with concentric rings of hemorrhage and necrosis with poor demarcation at the advancing front of the infarct, as shown in Fig. 10–5. Bronchial involvement is easier to see in smaller lesions but if sought can be seen in larger lesion as well. Histologically, the affected lung tissue shows hemorrhage and fibrin in alveolar spaces and, usually, a lack of neutropenia. Alveolar septa are necrotic. Large numbers of fungi proliferate through the vasculature and parenchyma, often growing in radiating balls referred to as “sunburst” patterns.8,55

FIGURE 10–5 Invasive aspergillus pneumonia, producing a large, rounded hemorrhagic infarct that is not pleural-based.

Aspergillus Tracheobronchitis

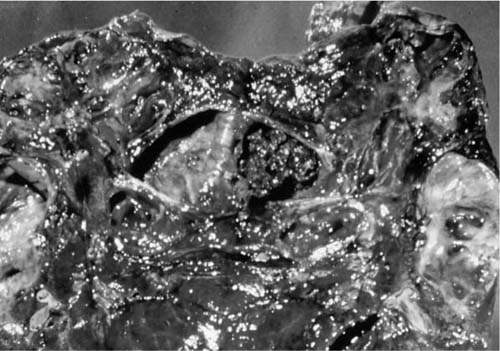

Occasionally, immunosuppressed patients presenting with fever and respiratory symptoms have predominant airways involvement with Aspergillus infection. Grossly, the airways contain a thick, yellow pseudomembrane consisting of fibrin and large numbers of Aspergillus mycelia, as illustrated in Fig. 10–6.14,70–72 Invasion of the bronchial walls by hyphae is usually seen.14 The lesion can be considered as part of the spectrum of invasive aspergillosis, but without the extensive parenchymal infiltration and infarction. The diagnosis can be made by bronchoscopy, but removal of the pseudomembrane may lead to fatal hemorrhage. Aspergillus infection confined to the bronchial mucosa may involve the bronchial stump after lung resection.73

Chronic Cavitary Aspergillosis

Chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis is a relatively uncommon form of Aspergillus infection that typically occurs as a complication of preexisting chronic lung disease, such as emphysema, sarcoidosis, treated tuberculosis, and other fibrosing lung diseases.18–77 The patient may be mildly immunocompromised because of such problems as alcoholism, diabetes mellitus, or corticosteroids therapy. Fever, cough with sputum, and weight loss are common complaints, and chest films show upper lobe infiltrates with thick-walled cavities. Thus the disease imitates the deep mycoses and tuberculosis in presentation. Aspergillus spp. are easily cultured from the lungs, and serum precipitins usually are positive.

FIGURE 10–6 Large bronchi containing a thick membrane of inflammation and fungi in tracheobronchial aspergillosis.

North America Blastomycosis

B. dermatitidis is a dimorphic fungus that grows as a mycelium at room temperature and converts to the yeast phase at 37°C. The yeast forms are usually found in infected tissues, although mycelia can rarely occur as well. Soil is generally considered to be the natural habitat of B. dermatitidis, although the organism has only occasionally been cultured from soil samples. Epidemiologic studies of blastomycosis have been incomplete because of difficulties in isolating the organism from nature and also because skin and serologic tests are unreliable. Endemic areas, therefore, have been defined only by case finding. They include the southern, southern central, and Great Lakes areas of the United States and midwestern Canada. Cases can occur well outside of these areas, however, and have been reported as far away as Africa and South America.78

Clinical Manifestations

Blastomycosis usually occurs in young to middle-age adults; men are affected more often than women. Several different clinical syndromes can occur.78–83 On initial exposure to the organism, an acute pneumonia develops. Most of these patients manifest high fever, chills, and cough accompanied by patchy chest infiltrates. This form of the disease is generally self-limited and patients recover within several weeks. However, the pneumonia is associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in a minority of cases, and prompt antifungal therapy can be lifesaving.82 Asymptomatic or subclinical acute pneumonia, analogous to asymptomatic primary histoplasmosis or coccidioidomycosis, has also been documented in a few cases from local epidemics. Most investigators believe that asymptomatic infection by B. dermatitidis is more common than currently appreciated, and that as soon as more reliable immunologic tests are available, the frequent occurrence of this form of the disease will be documented. In a few patients with acute pneumonia, the infection cannot be controlled and there is rapid spread throughout both lungs (progressive pulmonary blastomycosis). The radiologic features of blastomycosis have been reviewed.84 Because the most common radiographic appearance is that of a mass or infiltrate, distinction from primary lung cancer may be difficult.85 Extrapulmonary involvement may occur as well in this form of the disease, and mortality is high. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis from inoculation is a hazard to pathologists handling specimens of pulmonary blastomycosis.86 Blastomycosis has been described as an opportunistic infection in AIDS.87

Chronic (recurrent or reactivation) blastomycosis occurs months to years following an episode of symptomatic acute pneumonia that appeared to have resolved. In some patients, a previous acute pneumonia is not documented and the initial infection is assumed to have been asymptomatic or subclinical.72,88,89

Chronic blastomycosis may be confined to the lung, or it may involve extrapulmonary organs, or both. When it disseminates, the skin is the most frequent extrapulmonary site of involvement.

Histopathologic Features

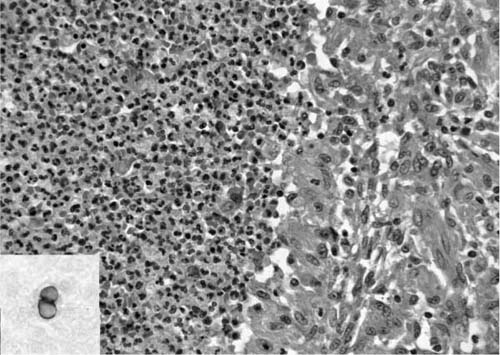

The usual tissue response in the lung to B. dermatitidis infection is necrotizing granulomatous inflammation.90,91 The granulomas characteristically are composed of a core of necrotic neutrophils surrounded by epithelioid, often palisading, histiocytes, as seen in Fig. 10–7. Both caseation and calcification are absent. Nonnecrotizing granulomas may be found with the necrotizing granulomas, and in a few reported cases such sarcoid-like granulomas have been the only tissue reaction.

The organisms can be found intermingled with necrotic neutrophils at the center of the granulomas, or they may be present within surrounding histiocytes. They are round, budding yeasts that average 8 to 15 μm in diameter and may range up to 30 μm. They are easily visualized in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections, where a thick, somewhat refractile cell wall can be seen surrounding basophilic protoplasm. The base of the budding cell is broad, 4 to 5 μm, compared with the narrow-based bud of Cryptococcus neoformans (Fig. 10–7). B. dermatitidis also lacks the mucinous capsule of C. neoformans. As with other fungi, special stains [Grocott’s methenamine silver, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)] facilitate their identification. Mycelial forms are rarely encountered in tissue.92 The characteristic appearance of the fungus allows cytologic diagnosis from respiratory secretions.93

Candidiasis

Candida species are a common cause of infection in patients who are immunocompromised, either due to an underlying malignancy or because they are receiving cytotoxic therapy. Indwelling venous catheters, prolonged antibiotic therapy, severe burns, AIDS, and abdominal surgery also predispose persons to infection by this organism.94–98 Candida albicans is the most frequent species isolated; other medically important species include C. guillermondii, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, and C. tropicalis.99,100 Torulopsis glabrata is sometimes classified as C. glabrata; in this chapter it is generically considered Torulopsis and is discussed later (see Other Fungal Diseases). The various species of Candida all produce similar disease, both clinically and pathologically. Candidiasis is sometimes called moniliasis, from the previously used generic designation Monilia. Infection by these organisms can be either superficial or deep. Superficial infections involve mucosal surfaces and are very common, especially in the oral cavity. In deep infections, there is hematogenous spread to multiple organs and the prognosis is grave.

FIGURE 10–7 Portion of a granuloma due to blastomycosis with necrosis and neutrophils on the left and epithelioid cells on the right [hematoxylin and eosin (H&E, ×315]. Inset: broad-based budding of blastomycosis (GMS, ×315).

The lung is frequently involved in disseminated candidiasis, but clinically significant lung involvement is less common than fungemia from other fungi.99,101–103 More over, there are no specific clinical or radiographic features of pulmonary candidiasis.101 Positive sputum cultures are not helpful because the organism is a common saprophyte in the oral cavity, skin, and respiratory tree. The diagnosis can be made with certainty, therefore, only by identifying the organism within tissue.

Histopathologic Features

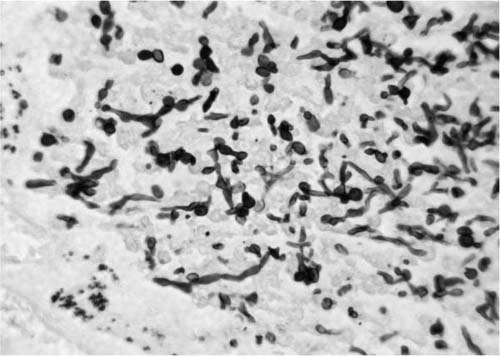

Two distinct patterns of pulmonary infection by Candida spp. occur, depending on whether the infection results from hematogenous spread or by aspiration.99,104–106 In the hematogenous variant of pulmonary candidiasis, the lung is one of multiple organs affected. This form of candidiasis is characterized by multiple miliary (2 to 4 mm) nodules that are spread randomly throughout the lung parenchyma. The nodules consist of central necrosis with varying amounts of acute inflammation, depending on whether the patient is neutropenic. Clusters of organisms are present within the necrotic zones. Candida sp. can be seen as yeasts, often budding, hyphae, or pseudohyphae, as seen in Fig. 10–8. They can be visualized with H&E in addition to PAS and Grocott’s methenamine silver stains, and they are weakly gram positive. The yeasts are ovoid, occasionally round, and measure up to 5 μm in the longer axis. Pseudohyphae are composed of elongated blastospheres attached to each other in a chainlike fashion resembling sausage links. The bulging rather than parallel walls and the constriction at the septa separate pseudohyphae from true hyphae. Hyphae average 3 to 5 μm in thickness, appearing thinner than Aspergillus sp. Although occasional organisms can be found within blood vessels,92 the extensive vascular invasion and infarction characteristic of invasive aspergillosis and mucormycosis are not seen.

Pulmonary candidiasis secondary to aspiration sometimes occurs in moribund patients and is of little clinical significance. It is generally found in individuals who have associated candidiasis involving the oral cavity, esophagus, larynx, or trachea. This form of the disease is characterized by foci of acute bronchopneumonia that often contain food particles as evidence of aspiration. Abscess formation may also occur. These lesions further differ from hematogenous candidiasis in that they are distributed predominantly around bronchioles rather than randomly throughout the parenchyma. In cases of preterminal aspiration, clusters of organisms are seen in the airspaces without any associated inflammatory reaction. Such aspiration explains the identification of Candida sp. in postmortem lung cultures from patients who have no histologic pneumonia. Such culture results usually can be ignored.

FIGURE 10–8 Photomicrograph showing typical yeasts and pseudohyphae of Candida species (GMS, × 420).

Candida sp. frequently are isolated from BAL or sputum of patients with AIDS.107–109 Occasionally the presence of the organism is indicative of pneumonia, but usually Candida represents contamination from oral candidiasis (thrush).108 In one study, identification of Candida sp. in BAL fluid correlated significantly with clinical evidence of oral candidiasis.67 Clinical judgment and the exclusion of other causes for pulmonary infiltrates should allow one to determine whether Candida sp. in respiratory secretions means candidal pneumonia.

Coccidioidomycosis

Coccidioides immitis, the causative organism of coccidioidomycosis, is found in the southwestern United States throughout an area extending approximately from the San Joaquin Valley of California to El Paso, Texas, and from northern Arizona to southern Sonora, Mexico, as well as isolated other areas in the Western Hemisphere.109–111 However, the increasing popularity of long-distance travel has resulted in coccidioidomycosis being diagnosed far outside its endemic area, so-called traveler’s coccidioidomycosis.112 Early descriptions of infections with this organism from San Joaquin Valley led to the familiar term valley fever for coccidioidomycosis.112 The organism received its name from a fancied resemblance to intestinal parasites of the subclass Coccidia, a veterinary and occasionally human pathogen. Because of difficulties in pronunciation and spelling of the term coccidioidomycosis, physicians in the endemic area usually refer to the disease as “cocci,” as will be done here.

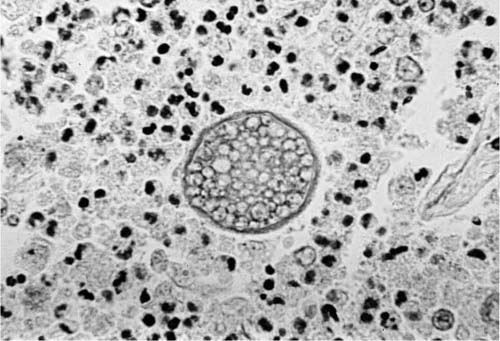

Cocci is a dimorphic soil fungus, and its likelihood of causing human disease is related to cycles of wet and dry weather, as cocci mycelia grow up to the soil surface during wet weather, dry out when the rains stop, and are then dispersed by wind.113 Distribution of infectious spores by wind can initiate outbreaks of cocci.114 In tissue, the organism exists largely in the form of spherical yeasts called spherules. The very smallest of these, which develop from endospores, are in the size range of 4 to 5 μm; as they mature they may reach sizes of 40 to 60 μm and develop many round endospores within the spherules, as seen in Fig. 10–9.115–117 Eventually, the spherules rupture, leaving an empty cystlike structure. The spherule has a relatively thick refractile wall that aids its identification in tissue.

There are virtually no other fungi that have the morphologic appearance of mature spherules. Rhinosporidium seeberi is somewhat similar but is confined to the skin, usually the nose. The spherules of adiaspiromycosis are larger (50 to 500 μm), have a trilaminar wall, and have no endospores.118 Occasionally, aspirated foreign material in the lungs, such as parts of the seeds of leguminous plants (pulses), may somewhat resemble the mature endosporulating spherules of cocci. Immature spherules, in which endospores are not apparent, have a far less specific morphology and may mimic such agents as Pneumocystis jiroveci/carinii, Candida sp., Torulopsis glabrata, Histoplasma capsulatum, and other small yeasts, when seen only as endospores or very small spherules. Medium-size spherules are in the size range of that of C. neoformans and B. dermatitidis.

FIGURE 10–9 High magnification of a mature spherule of coccidioidomycosis with numerous endospores (H&E, × 340).

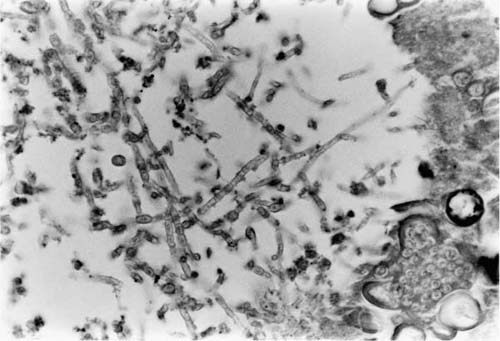

Although microbiologic culture identifies cocci, such cultures may take several weeks, and a search for mature spherules is the best way to solve the problem of identification quickly. Occasionally, cocci may develop hyphal forms, as depicted in Fig. 10–10. This change is seen most commonly in cavitary lesions and may be seen in up to one third of cases of cavitary cocci.119–121 On fine-needle aspirate of a solitary pulmonary nodule, the presence of hyphae does not exclude the possibility of cocci. Again, endosporulating spherules, if present, indicate the true nature of organism.

In culture, as in nature, cocci develops true mycelia, which is the basis for its classification as a perfect fungus. The mycelia separate into segments capable of giving rise to the yeast or spherule forms in tissue. These segments are the arthrospores (arthroconidia) and constitute the infectious form of the organism. Thus there is virtually no risk of contracting cocci from resected or autopsy tissue; however, laboratory culture plates are a real hazard for the accidental inhalation of arthrospores.122

Cocci is capable of producing a large variety of human infections involving the lung. These may be categorized as solitary nodule/infiltrate, chronic progressive cavitary disease, acute coccidioidal pneumonia, and miliary coccidioidomycosis. The latter two are seen most commonly in immunosuppressed patients, especially those with AIDS.

Primary Nodular Coccidioidomycosis

In endemic areas for cocci, the rate of infection among inhabitants is 3% per year.123 Thus, longtime dwellers in areas of endemic cocci would be expected to have acquired infection with this organism, usually in the form of a limited, self-healing pulmonary disease. Approximately 40% of the patients who acquire primary cocci have no symptoms and are identified retrospectively by the appearance of a solitary nodule on chest film together with seroconversion, or at autopsy or thoracotomy.124 Another 40% complain of a flu-like illness that may last as long as 4 to 6 weeks with malaise, fever, dry cough, and sometimes dyspnea. Serial radiologic studies in these patients show a localized pulmonary infiltrate that coalesces into a nodule over weeks to months. Serum precipitin antibodies rise quickly, but typically disappear within 3 months after onset of symptoms. Complement-fixing antibodies rise more slowly but persist for many months after the onset of systems.124 The newer latex particle agglutination test is a good screening test, but positive results should be confirmed by tube precipitation assays. The remainder of patients have more severe symptoms, which bring them to medical attention, and their diagnosis is made by combination of radiologic findings and seroconversion. Skin testing for cocci with coccidioidin or spherulin antigens is helpful diagnostically if one can demonstrate recent conversion, but in endemic areas most of the population is positive.

FIGURE 10–10 A tangle of hyphal forms of Coccidioides immitis, as may be seen in cavitary disease. A few spherules are seen at lower right (H&E, × 210).

Although in a great many cases the episode of initial cocci remains only an isolated radiologic finding and never produces further symptoms, occasionally the lesion comes to medical attention. Sometimes a primary cocci granuloma grows over time and can be called a coccidioidoma, that is, an enlarging neoplasm-like granuloma analogous to histoplasmoma or tuberculoma, as illustrated in Fig. 10–11.110,118,125 In many cases, it is not apparent that the noncalcified, enlarging nodule on chest film is due to cocci and especially in an older, smoking patient, the patient is evaluated to rule out carcinoma. In a nonendemic area, positive serologic tests for cocci are helpful in this regard. However, fine-needle aspiration biopsy of such lesions produces the diagnosis in a large percentage of patients.126,127 Others have used larger needles to obtain thin cores of tissue to recognize the presence of cocci. The risk of pneumothorax and bleeding, the operator’s skill, and the necessity of getting a diagnosis are all balanced to determine the precise mode of biopsy.

FIGURE 10–11 A well-demarcated “coccidioidoma” or enlarging granuloma of C. immitis.

In some cases the initial cocci lesion, a localized granulomatous pneumonia, coalesces into a fibrocaseous granuloma, enlarges, and becomes cavitary by involvement of a bronchus. Such a developing cavity can be observed on chest film and often produces symptoms.128 Progression of primary cocci infection with cavity formation is especially likely to happen in a patient with diabetes mellitus. Occasionally, a cavitary cocci nodule ruptures into the pleural space, producing a severe purulent pleuritis, which necessitates urgent surgical intervention. Such an example is seen in Fig. 10–12. In most cases, cavitary cocci nodules are removed in diabetics because of the small likelihood that they will spontaneously heal and because they continue to produce symptoms.

The gross pathology of primary cocci in the localized pneumonic form is not seen very often but consists of an infiltrate of caseating and noncaseating granulomas, similar to those of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The noncaseating granulomas consists of a mixture of epithelioid cells and Langhans’ and foreign body giant cells with a proliferation of lymphocytes and macrophages.117 Thus, on a small biopsy such granulomas may be indistinguishable from those of sarcoidosis. Caseation consists of granular eosinophilic material, occasionally with some ghost outlines of vessels and connective tissue; sometimes neutrophils also are prominent. The solitary fibrocaseous nodule is a macroscopic version of the caseating granuloma, with a wall of fibrous tissue admixed with lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, epithelioid cells, and occasional giant cells.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree