An acute decompensation of heart failure resulting in hospital admission represents a critical juncture in the natural history of the disease, as evidenced by poor mortality and readmission outcomes after hospital discharge. For this reason, a number of new short-term vasoactive therapies have been or are being tested in clinical trials. Furthermore, in response to unacceptable readmission rates, there has been intense interest in improving the transition from hospital discharge to the outpatient arena. Between these 2 areas of focus exists an often overlooked internal transition from acute vasoactive therapies to oral chronic heart failure medications. This transition from acute presentation to the rest of the hospital stay forms the basis of this review.

Heart failure (HF) is a syndrome of progression whereby an acute decompensation represents a seminal event in its natural history. This is supported by the staggering morbidity and mortality outcomes after admission for acute decompensated HF (ADHF), far different from clinical trial data in stable patients. Observational and registry-derived data have documented that the rate of readmission is 20% at 30 days, with annual mortality of 33%. Appropriately, ADHF has been an area of intense focus, with numerous therapies having reached phase 3 clinical trials over the past 15 years. Unfortunately, as listed in Table 1 , although many new therapies have shown improvements in dyspnea relief, none have consistently demonstrated the ability to decrease hard clinical end points such as hospitalizations and mortality. When this disconnect is considered from a distance—an improvement in the short-term goal of symptom relief but no change in the long-term goal of readmissions or mortality—it suggests that an underexplored focus is the transition from the acute to long-term therapies.

| Study | Endpoint | Number of Patients (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Drug | Placebo | |||

| EVEREST (Tolvaptan) | Change in dyspnea at 1 day (improved) | 1835 (74.3) | 1829 (68) | <0.001 |

| All-cause mortality ∗ | 537 (25.9) | 543 (26.3) | 0.68 | |

| ASCEND | Improvement in self-assessed dyspnea at 24 hours | 2384 (68.2) | 2320 (66.1) | 0.007 |

| (Nesiritide) | 30 day death/heart failure re-hospitalization | 321 (9.4) | 345 (10.1) | 0.31 |

| PROTECT | Success † | 551 (40.6) | 244 (36) | 0.04 |

| (Rolofylline) | Mortality at 180 days | 243 (17.9) | 118 (17.4) | 0.82 |

| RELAX-AHF | Markedly or moderately improved Likert scale dyspnea | 389 (68) | 362 (63) | 0.0865 |

| (Serelaxin) | Days alive out of hospital up to day 60 | 281 (48.3) | 277 (47.7) | 0.37 |

† Moderate or marked improvement in dyspnea at 24 and 48 hours without any evidence of death, readmission, worse symptoms, worse renal function (increase of serum Cr of 0.3 mg/dl to day 7).

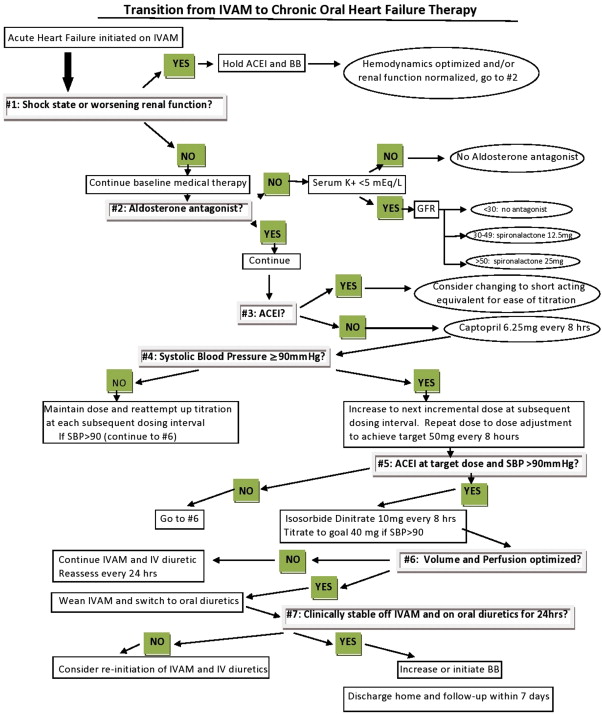

In contrast to the plethora of trials of new ADHF therapies, there are no randomized trials evaluating approaches to transitioning improving decompensated patients to long-term HF medical therapy and then home. There is a dire need for studies in this area to help establish clear pathways to move patients from acute to chronic care. In an era when unacceptable readmission rates have led hospitals to focus on transitioning care from discharge and beyond, this internal transition point has not been addressed. The transition of care from acute presentation to the rest of the hospital stay and to discharge constitutes the content of this review. Figure 1 is a graphical adaptation of the text into a work-flow tool that transitions patients from intravenous (IV) vasoactive medication (IVAM) to oral HF therapy. For the purposes of this review, the term “IVAM” is used to refer to IV vasodilators and positive inotropic agents.

Baseline Medical Therapy

In the pathophysiology of an ADHF presentation, there exists a neurohormonal “storm” with high levels of angiotensin II, aldosterone, and vasopressin. It is generally accepted, and now emphasized in the American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association 2013 guidelines, that in the absence of compelling contraindications, neurohormonal blockade, which forms the basis of long-term HF medical therapy, should be maintained during the administration of IVAM ( Figure 1 , cardinal point #1). Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors have theoretical benefits even in the acute setting and should be reduced or temporarily discontinued only in the setting of symptomatic hypotension or significant worsening renal function until improvement. Initial concerns regarding potential negative inotropic properties of β blockers have recently been allayed by accumulating evidence of benefit with their maintenance during an acute exacerbation. A recent randomized, controlled trial tested the hypothesis that continuation was noninferior to withdrawal in 169 patients previously receiving stable doses of β blockers. The investigators found no difference in dyspnea and general well-being at 3 days or in length of stay and mortality between the 2 groups. Data from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) registry suggested a potential benefit: an analysis of 2,373 patients eligible for β blockers at discharge showed that withdrawal of β blockers compared with continuation was associated with a higher adjusted risk for mortality at 60 to 90 days (hazard ratio 2.34, 95% confidence interval 1.20 to 4.55, p = 0.013). These data support the concept that planning for the transition starts at the time of admission when all HF medications should be reviewed and continued in the absence of shock states or significant worsening renal function.

Aldosterone Antagonists

Aldosterone receptor antagonists are indicated for the treatment of chronic systolic HF in patients with New York Heart Association class II to IV symptoms. Although their role in the treatment of patients with ADHF is less clear, there are many reasons to consider initiation during the inpatient setting. First, the effect of aldosterone receptor antagonists on blood pressure has been demonstrated to be minimal, therefore allowing initiation without hindering the institution of other therapies, and for this reason they have been incorporated early as cardinal point #2 in Figure 1 . Second, the addition of aldosterone blockade may block the increase in aldosterone that occurs after aggressive diuresis. Furthermore, initiation during the inpatient admission facilitates closer monitoring of the serum potassium level response. This is particularly important considering the high rates of hyperkalemia with aldosterone receptor antagonists, as highlighted by the Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization and Survival Study in Heart Failure (EMPHASIS-HF) trial, in which approximately 12% of patients developed serum potassium levels >5.5 mEq/L. Finally, as with other therapies, inpatient initiation is known to result in better utilization.

Aldosterone Antagonists

Aldosterone receptor antagonists are indicated for the treatment of chronic systolic HF in patients with New York Heart Association class II to IV symptoms. Although their role in the treatment of patients with ADHF is less clear, there are many reasons to consider initiation during the inpatient setting. First, the effect of aldosterone receptor antagonists on blood pressure has been demonstrated to be minimal, therefore allowing initiation without hindering the institution of other therapies, and for this reason they have been incorporated early as cardinal point #2 in Figure 1 . Second, the addition of aldosterone blockade may block the increase in aldosterone that occurs after aggressive diuresis. Furthermore, initiation during the inpatient admission facilitates closer monitoring of the serum potassium level response. This is particularly important considering the high rates of hyperkalemia with aldosterone receptor antagonists, as highlighted by the Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization and Survival Study in Heart Failure (EMPHASIS-HF) trial, in which approximately 12% of patients developed serum potassium levels >5.5 mEq/L. Finally, as with other therapies, inpatient initiation is known to result in better utilization.

Tailored Therapy and Oral Vasodilators

The use of tailored therapy to achieve prespecified hemodynamic goals with the use of a pulmonary artery catheter in a broad group of patients with ADHF was found not to be superior to clinical assessment in the Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness (ESCAPE). In practice, we continue to conceptually “tailor” therapy. By substituting the pulmonary artery catheter with clinical assessment for the estimation of filling pressures (volume) and perfusion (cardiac output), decisions are often made regarding the need for and duration of vasoactive therapy in patients with ADHF. An often raised concern with IVAM is that after acute achievement of hemodynamic goals, withdrawal will lead to a recurrent increase in filling pressures and/or a decrease in cardiac output. There is good pathophysiologic evidence to refute this notion, mechanistically explained whereby a reduction in filling pressures decreases atrioventricular valve regurgitation and thus augments forward stroke volume. Furthermore, reductions in filling pressures have been shown to decrease neurohormonal activation, which may diminish afterload-contractility mismatch. Most important, the long-term success of IVAM may be dependent on instituting and up-titrating a regimen of oral vasodilators and neurohormonal blockade as a chronic treatment alternative while withdrawing acute IV therapies ( Figure 1 , cardinal points #3 to #5).

There are currently no large randomized trials evaluating strategies to transition from IVAM to oral HF therapies. A number of small, single-center studies in advanced HF populations provide guidance and evidence of potential benefit. Two earlier studies demonstrated the utility of dobutamine and milrinone in facilitating up-titration of ACE inhibitors, a strategy that resulted in decreased hospitalizations in a cohort of sick patients. Other, larger series have documented benefit with the use of the IV vasodilator sodium nitroprusside to tailor long-term therapy.

Investigators at the University of California, Los Angeles, studied this approach in a seminal paper published in 1997. The study cohort consisted of 25 patients referred for cardiac transplantation, New York Heart Association class III or IV, and with cardiac indexes ≤2.2 L/min/m 2 in whom repeat hemodynamic assessments after discharge were available. All patients were managed with pulmonary artery catheters to achieve hemodynamic goals of pulmonary capillary wedge pressure ≤15 mm Hg, right atrial pressure ≤8 mm Hg, and systemic vascular resistance of 1,000 to 1,200 dyne · s · cm 5 , while maintaining systolic blood pressure ≥80 mm Hg with the use of nitroprusside and diuretics. After these goals were reached or 48 hours had elapsed, captopril and isosorbide dinitrate were started, and nitroprusside was weaned if hemodynamic goals were maintained. At discharge, 24 of 25 patients were receiving ACE inhibitors at substantially higher doses compared with baseline. Follow-up hemodynamic analysis performed at 8 ± 6 months revealed sustained hemodynamic benefit without any significant change in medication doses. The investigators concluded that long-term therapy tailored to an acute hemodynamic response provides sustained hemodynamic and symptomatic benefit. This approach is still used by many HF clinicians today, often with the estimation of hemodynamics by presentation, physical examination, and echocardiography.

In a larger study, 175 patients admitted with ADHF and cardiac indexes ≤2 L/min/m 2 at the Cleveland Clinic were analyzed according to treatment with and without nitroprusside. Although the primary outcome demonstrated that patients treated with nitroprusside had lower rates of all-cause mortality, it is important to note that an aggressive algorithm of simultaneous oral vasodilator up-titration was successfully followed. This accounted for an increase in the number of patients receiving ACE inhibitors and oral vasodilators at discharge compared with baseline. The investigators concluded that IV vasodilator therapy to optimize current oral HF therapy might be associated with favorable long-term clinical outcomes in patients hospitalized for ADHF.

An important question is which oral vasodilator or neurohormonal inhibitor is appropriate for the transition from IV vasoactive therapy. Intuitively, the direct vasodilator hydralazine is appealing, with the addition of nitrates to mimic the effects of preload and afterload reduction offered by nitroprusside; however, ACE inhibitors are the current standard of care in therapy for chronic systolic HF. Once again, insight is provided from a study of an advanced HF population in the Hydralazine versus Captopril (Hy-C) trial. One hundred seventeen patients with left ventricular ejection fractions ≤20%, New York Heart Association class III or IV symptoms, and cardiac indexes ≤2.2 L/min/m 2 or pulmonary capillary wedge pressure ≥20 mm Hg were treated with nitroprusside and diuretics to achieve prespecified hemodynamic goals. Patients were subsequently randomized to either up-titration of captopril or hydralazine plus nitrates to maintain hemodynamic goals as nitroprusside was weaned. After 8 ± 7 months of follow-up, actuarial 1-year survival was significantly greater in the captopril group (81% vs 51%, p = 0.05), driven largely by a reduction in sudden cardiac death. It is important to remember that much of these data predate the use of β blockers, which have further reduced mortality and morbidity in addition to ACE inhibition.

These observational studies are encouraging and require confirmation in larger randomized trials but suggest that (1) IVAMs can be used to successful bridge to long-term oral HF therapy, (2) IV vasodilators may be superior to inotropes for this purpose, and (3) ACE inhibitors should be preferred over hydralazine and nitrates in the transition from IVAMs. On the basis of the results of the Hy-C trial and a plethora of evidence supporting ACE inhibitors as first-line therapy for chronic systolic HF, we suggest a strategy of active up-titration of ACE inhibitors during IVAM and diuresis, followed by the addition of oral nitrates within the constraints of a safe blood pressure ( Figure 1 , cardinal points #3 to #5). In patients in whom ACE inhibitors are contraindicated (e.g., those with renal artery stenosis or angioedema), an angiotensin receptor blocker or hydralazine and nitrates should be substituted.

Finally, it is important to note that ever shortening lengths of stay, now averaging 5.3 days, often do not allow the achievement of meaningful doses of long-term HF therapy during the admission. Therefore, one intention in the transitional period is to continue the process of up-titration to guideline driven care shortly after discharge. The up-titration of appropriate therapy should continue seamlessly into the outpatient environment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree