Fig 1.

Axial image shows a right axillary lymph node with a fatty hilum (arrow) indicating a benign lymph node

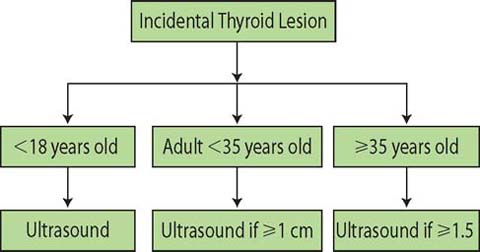

The thyroid gland is usually at least partially included on a chest CT exam. Thyroid nodules are extremely common in the adult population and the vast majority are benign. Recent guidelines have been published by Hoang et al. [2] to diminish the number of unnecessary follow-up exams. (Fig. 2). For adults ⩾=35 years of age, a follow-up ultrasound is recommended if the nodule is ⩾=1.5 cm. In adults <35 years of age, a follow-up ultrasound is recommended if the nodule is ⩾=1 cm. In addition, any nodule in the pediatric age group or any nodule regardless of patient age that is fluorodeoxyglucose-avid on positron emission tomography (PET) or with evidence of invasion or adjacent lymphadenopathy should be assessed by ultrasound.

Fig 2.

The exact guideline for the evaluation of incidental thyroid nodules depends on the age of the patient and the size of the lesion

Chest Wall

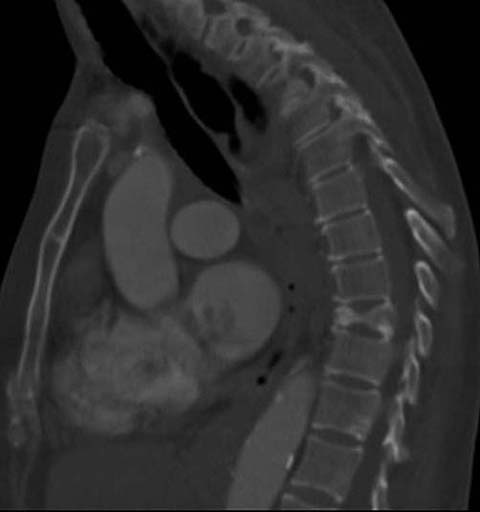

Coronal and sagittal reformatted images are useful in evaluating skeletal structures. The ribs are problematic because a single rib is not visualized on a single axial image. The use of bone windows improves visualization of the lateral aspects of the ribs on sagittal images; posterior aspects are best visualized on coronal reformatted images. Rib lesions will be more obvious while scrolling through the data set than if each image is independently reviewed. Sternal fractures can be missed on axial images because of the plane of imaging but are very well depicted on sagittal views. Likewise, the vertebral column is ideally suited for review on sagittal views, where compression fractures (Fig. 3) and lytic and sclerotic lesions may be more obvious than on axial images.

Fig 3.

Sagittal image demonstrating a compression fracture of the T9 vertebral body; the fracture was not present on the prior exam

CT is not ideal for breast imaging. However, assessment of breast tissue should be included in the search pattern. Breast cancer may be visible as an asymmetric soft-tissue mass that sometimes shows enhancement with the administration of intravenous contrast. Skin thickening from tumor or radiation can also be visualized, as well as evidence of prior surgery such as lymph node dissection. The presence of collateral vessels in the chest wall may alert the clinician to the presence of vascular pathology elsewhere, such as a stenosis or occlusion at the thoracic inlet.

Subcutaneous nodules such as metastases occur more commonly with lung cancer, breast cancer, or melanoma. However, soft-tissue nodules of the chest wall are more typically related to benign etiologies such as sebaceous cysts, or, when involving the anterior upper abdominal wall, injection sites from subcutaneous administration of medication. Occasionally, abnormalities such as calcifications in patients with scleroderma or neurofibromas in patients with neurofibromatosis will be present.

Upper Abdomen

Liver

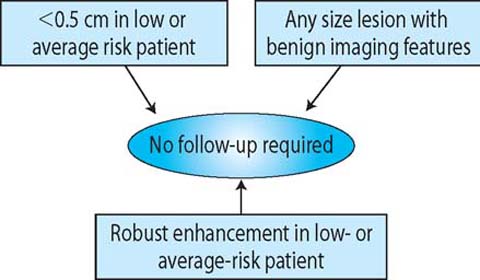

Although commonly encountered, most liver lesions are benign, even in patients with known malignancy. Berland et al. [3] published guidelines for the management of incidental liver findings on CT (Fig. 4). They categorized liver lesions based on the size and appearance of the lesion and the relative risk of the patient. Hepatic cysts are very common and present as sharply marginated, low-attenuation lesions of <20 Hounsfield units (HU). Typical hemangiomas show peripheral, nodular enhancement that fills in centrally on delayed images (Fig. 5). Findings that are more concerning include low-attenuation lesions with ill-defined margins, enhancement <20 HU, and heterogeneity. These lesions will require additional imaging and/or intervention. Hyperenhancing liver lesions may be encountered — particularly on CT angiogram for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism or evaluation of the aorta — and may represent a transient hepatic attenuation difference (THAD) flow artifact or focal nodular hyperplasia. For lesions measuring up to 1.5 cm, in patients with a low or average risk of malignancy, hyperenhancing lesions can be considered benign and no further imaging is recommended [3].

Fig 4.

Liver lesions do not always require follow-up imaging; rather, the decision depends on the imaging features and size of the lesion and the risk to the patient

Fig 5.

Axial image demonstrates a lesion in the right lobe of the liver with peripheral contrast enhancement (arrow) and a central low density. The findings are consistent with the “peripheral puddling” contrast enhancement pattern seen in hemangiomas

Kidneys

Renal cysts are very common. The features consistent with a cyst on unenhanced CT scans include a well-defined margin, homogeneous attenuation of 0–20 HU, absence of nodularity, septa, wall thickening, and nodular or thick calcification. Thin calcification of the wall is an acceptable benign feature of a cyst. If these features are present, no further work-up is necessary. A homogeneously dense lesion, with an intensity >70 HU and measuring <3 cm in diameter, is most likely a hyper-dense cyst. Lesions that do not demonstrate these benign imaging features will require additional work-up [3].

Spleen

Incidental splenic lesions are not as common as incidental hepatic lesions but they do occur. If the lesion is consistent with a splenic cyst, i.e., imperceptible wall, near-water attenuation (<10 HU), and lack of contrast enhancement, no further work-up is necessary. If these criteria are not met, the lesion may still be benign when it has the following imaging features: homogeneous attenuation of <20 HU, lack of contrast enhancement, and smooth margins. Features that should raise suspicion of a neoplasm include heterogeneous contrast enhancement, irregular margins, necrosis, and evidence of invasion (Fig. 6). When suspicious features are present, follow-up imaging or intervention is warranted [3].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree