Fiberoptic Bronchoscopy

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

• Fiberoptic bronchoscopy (FOB) was developed by Shigeto Ikeda in the 1960s.

• FOB has become a vital procedure for pulmonologists, with nearly 500,000 procedures performed in the United States every year.1

• The rise of the field of interventional pulmonology has increased the diagnostic and therapeutic range of the bronchoscope.

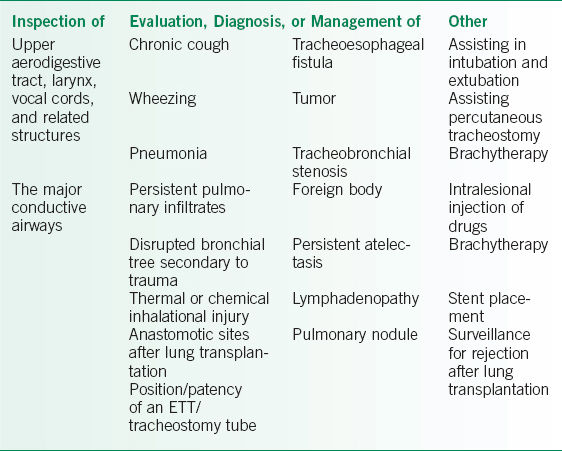

• As technology has improved, indications for FOB have increased (Table 4-1).

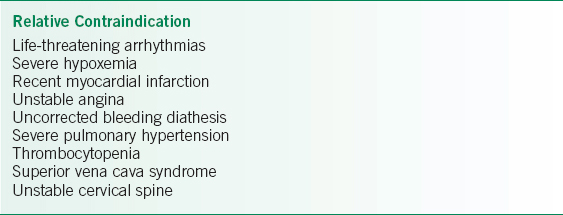

• Most contraindications are relative, and potential reward must merit the possible risk (Table 4-2). The major absolute contraindication is a significant increase in intracranial pressure (ICP), as coughing during the procedure can further increase ICP leading to brain herniation.

TABLE 4-1 INDICATIONS FOR FIBEROPTIC BRONCHOSCOPY

TABLE 4-2 RELATIVE CONTRAINDICATIONS TO BRONCHOSCOPY

Prebronchoscopy Evaluation

• In an American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) survey, a majority of operators obtain a preprocedure chest radiograph, coagulation studies, and complete blood count. Less than one-half obtain an EKG, arterial blood gas, electrolytes, or pulmonary function tests.2 Routine preprocedure labs are not absolutely indicated unless specific concerns exist.

• Cardiac evaluation in patients with known coronary disease undergoing elective bronchoscopy can be considered, and guidelines have been published by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association.3

Procedural Medications

• Medications are commonly used before and during bronchoscopy to facilitate a safe, comfortable, and successful procedure.

• Antisialogogues are used with the intent of drying secretions and reducing the vasovagal response.

Atropine 0.4 mg IM is the antisialogogue most commonly used.

Atropine 0.4 mg IM is the antisialogogue most commonly used.

There are no convincing data that antisialogogues are efficacious, and because of the side effects, they are not recommended on a routine basis.4

There are no convincing data that antisialogogues are efficacious, and because of the side effects, they are not recommended on a routine basis.4

• Benzodiazepines play a central role in providing amnesia and anxiolysis.

Midazolam given parenterally is often used for its fast onset of action and short half-life.4

Midazolam given parenterally is often used for its fast onset of action and short half-life.4

Lorazepam has been used as a preprocedure medication with improved patient satisfaction at 24 hours versus placebo.

Lorazepam has been used as a preprocedure medication with improved patient satisfaction at 24 hours versus placebo.

Flumazenil, a competitive inhibitor of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor, can be used to reverse the sedative effects of benzodiazepines, though it should generally be avoided as it can precipitate withdrawal seizures.

Flumazenil, a competitive inhibitor of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor, can be used to reverse the sedative effects of benzodiazepines, though it should generally be avoided as it can precipitate withdrawal seizures.

• Opiates decrease the laryngeal reflexes and cough response, and provide some anxiolysis.

Fentanyl given parenterally is commonly used, again because of its short onset of action.4

Fentanyl given parenterally is commonly used, again because of its short onset of action.4

Meperidine has been used pre- and intraprocedurally, but its use is increasingly discouraged because of its active metabolites, long half-life, and increased risk of seizures.

Meperidine has been used pre- and intraprocedurally, but its use is increasingly discouraged because of its active metabolites, long half-life, and increased risk of seizures.

Naloxone reverses opiate sedation through direct competitive inhibition. It should only be used in cases of a significant narcotic overdose. Repeated doses or a continuous infusion may be required.

Naloxone reverses opiate sedation through direct competitive inhibition. It should only be used in cases of a significant narcotic overdose. Repeated doses or a continuous infusion may be required.

• Topical anesthesia to the upper aerodigestive tract, glottic area, and bronchial tree can be accomplished by the application of lidocaine, benzocaine, tetracaine, or historically, cocaine.

Lidocaine is the most commonly used topical anesthetic for FOB because of its fast onset of action and wide therapeutic window. It is applied in the glottic area, as well as directly on the tracheobronchial tree.5

Lidocaine is the most commonly used topical anesthetic for FOB because of its fast onset of action and wide therapeutic window. It is applied in the glottic area, as well as directly on the tracheobronchial tree.5

Safety for lidocaine is well established at doses <7 mg/kg.5

Safety for lidocaine is well established at doses <7 mg/kg.5

Operators must be aware of the risk of methemoglobinemia when using topical anesthetics, even in small amounts. When it occurs, it can be reversed by administration of methylene blue.

Operators must be aware of the risk of methemoglobinemia when using topical anesthetics, even in small amounts. When it occurs, it can be reversed by administration of methylene blue.

• Propofol is a sedative-hypnotic drug with rapid onset and very short duration of action.5 Recovery time after an infusion is only minutes.

Titration of propofol takes experience to avoid the most common side effect, hypotension.

Titration of propofol takes experience to avoid the most common side effect, hypotension.

Many institutions require anesthesia support for administration during procedures, and therefore it is often not used during routine bronchoscopies.

Many institutions require anesthesia support for administration during procedures, and therefore it is often not used during routine bronchoscopies.

Monitoring

• The operator is ultimately responsible for the care and safety of the patient during the bronchoscopy.

• Additional assistance is required, including at least one respiratory therapist. A second assistant can be either a second respiratory therapist or a procedural nurse.

Assistants monitor the patient, record vital signs, administer and record medications, handle specimens, and assist with the bronchoscope and other equipment.

Assistants monitor the patient, record vital signs, administer and record medications, handle specimens, and assist with the bronchoscope and other equipment.

Special assistance is also needed when the patient is on a mechanical ventilator as insertion of a bronchoscope creates increased airway resistance.

Special assistance is also needed when the patient is on a mechanical ventilator as insertion of a bronchoscope creates increased airway resistance.

• Equipment for monitoring and supporting the patient should include continuous pulse oximetry and EKG, vascular access, supplemental oxygen, suction, and an automated blood pressure cuff.

• Additional equipment that should be immediately available includes that needed for endotracheal intubation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, vascular access, and needle decompression of pneumothorax.

Technique

• The most common patient position is supine, in bed, with the operator standing at the patient’s head.

• A transoral approach is often used, sometimes with insertion of a laryngeal mask airway or endotracheal tube, and sometimes with no artificial airway. A transnasal or transtracheostomy approach may also be utilized.

• During insertion of the bronchoscope, the operator should note abnormalities of the upper airway, false and true vocal cords, and glottic area. After passage through the cords, the trachea and tracheobronchial tree are examined to at least the first subsegmental level.

• After examination of the airways, diagnostic or therapeutic procedures may be attempted.

Postprocedure

• After the procedure, the patient requires monitoring in a postprocedure area until they have recovered from sedation.

• A patient cannot drive home from the procedure, and should not operate machinery or perform other potentially dangerous activity after the procedure.

• Postprocedure chest radiograph is generally obtained if needle aspirations or biopsies have been performed.

DIAGNOSIS

• A list of diagnostic uses of bronchoscopy can be seen in Table 4-1.

• Airway inspection is the mainstay of FOB and is generally performed with each procedure.

• Tumors, cysts, source of hemoptysis, signs of infection, foreign bodies, and altered airway anatomy are some of the more common abnormalities encountered during inspection.

• Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) consists of wedging the end of the FOB in a distal airway, followed by instillation of sterile saline through the bronchoscope with subsequent aspiration back through the bronchoscope, in 50-mL aliquots.

BAL is most useful for obtaining microbiologic cultures in diagnosing typical and atypical infections.

BAL is most useful for obtaining microbiologic cultures in diagnosing typical and atypical infections.

Cytology can be sent to aid in diagnosis of infection, malignancy, and occasionally diffuse lung disease.

Cytology can be sent to aid in diagnosis of infection, malignancy, and occasionally diffuse lung disease.

Cell count can show a preponderance of macrophages (normal), neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils, or a fairly even mix of cell types, which are indicative of different disease states.

Cell count can show a preponderance of macrophages (normal), neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils, or a fairly even mix of cell types, which are indicative of different disease states.

Successively bloodier BAL return aliquot is characteristic of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage.

Successively bloodier BAL return aliquot is characteristic of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage.

• Transbronchial lung biopsy is performed by passing biopsy forceps through the bronchoscope and into the lung, with the goal of sampling the distal airways parenchyma.

Biopsies are examined by experienced pathologists and can diagnose a wide range of pulmonary pathology.

Biopsies are examined by experienced pathologists and can diagnose a wide range of pulmonary pathology.

Transbronchial biopsies are generally performed using fluoroscopic guidance as the area being sampled is too distal for direct visualization, though this is not absolutely necessary.

Transbronchial biopsies are generally performed using fluoroscopic guidance as the area being sampled is too distal for direct visualization, though this is not absolutely necessary.

• Endobronchial biopsy is performed by passing biopsy forceps through the bronchoscope and sampling airways lesions in the larger airways under direct visualization.

• Transbronchial needle aspirations (TBNA) are used to take cytologic samples from enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes and mediastinal masses.

• Endobronchial ultrasound has led to a marked increase in the range of diagnostic uses of FOB.

Endobronchial ultrasound using a linear array ultrasound is becoming the standard of care for diagnosis of mediastinal lymphadenopathy and masses, replacing traditional TBNA, and can also be used for sampling masses within 3–4 cm of the large airways in experienced hands. It is also superior to other modalities for imaging the structure of the trachea and mainstem bronchi.

Endobronchial ultrasound using a linear array ultrasound is becoming the standard of care for diagnosis of mediastinal lymphadenopathy and masses, replacing traditional TBNA, and can also be used for sampling masses within 3–4 cm of the large airways in experienced hands. It is also superior to other modalities for imaging the structure of the trachea and mainstem bronchi.

Radial endobronchial ultrasound consists of a small, high-frequency ultrasound probe that can be guided through the bronchoscope into the distal airways, and advanced under fluoroscopic guidance with the goal of obtaining a real-time ultrasound image of a distal pulmonary nodule, allowing for biopsy and needle aspiration.

Radial endobronchial ultrasound consists of a small, high-frequency ultrasound probe that can be guided through the bronchoscope into the distal airways, and advanced under fluoroscopic guidance with the goal of obtaining a real-time ultrasound image of a distal pulmonary nodule, allowing for biopsy and needle aspiration.

• Along with radial endobronchial ultrasound, 3D navigational systems have been developed that are being increasingly used to sample pulmonary nodules.

TREATMENT

• A list of therapeutic uses of bronchoscopy is seen in Table 4-1.

• Advances in the field of interventional pulmonology have led to a large increase in the therapeutic uses of FOB, several of which are listed below. Some of these procedures are performed solely by these bronchoscopic specialists, while some are also performed by general pulmonologists.

Tracheobronchial narrowing from malignancy, strictures, or other pathology can be alleviated by stent placement or balloon dilatation, though the latter’s effects are much less permanent.

Tracheobronchial narrowing from malignancy, strictures, or other pathology can be alleviated by stent placement or balloon dilatation, though the latter’s effects are much less permanent.

Cryotherapy can remove malignancies or other airway obstructions. During cryotherapy, a probe is placed on the obstruction at extremely low temperatures, in essence freezing the obstruction to the probe and allowing for extrication.6

Cryotherapy can remove malignancies or other airway obstructions. During cryotherapy, a probe is placed on the obstruction at extremely low temperatures, in essence freezing the obstruction to the probe and allowing for extrication.6

Argon plasma coagulation can be used to stop focal bleeding or obliterate obstructive airway lesions, neodymium:yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) lasers may also do the latter.

Argon plasma coagulation can be used to stop focal bleeding or obliterate obstructive airway lesions, neodymium:yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) lasers may also do the latter.

Foreign body removals are usually performed using biopsy forceps and sometimes occur under fluoroscopic guidance depending on the density of the foreign body.

Foreign body removals are usually performed using biopsy forceps and sometimes occur under fluoroscopic guidance depending on the density of the foreign body.

Therapeutic aspiration of secretions is sometimes performed in the presence of atelectasis with respiratory failure.6

Therapeutic aspiration of secretions is sometimes performed in the presence of atelectasis with respiratory failure.6

Management of anastomotic stricture or dehiscence after lung transplantation can generally be managed by debridement or stenting.

Management of anastomotic stricture or dehiscence after lung transplantation can generally be managed by debridement or stenting.

Placement of one-way endobronchial valves will lead to collapse of selective subsegments of the lung and is being increasingly used in management of refractory, localized bronchopleural fistulas.

Placement of one-way endobronchial valves will lead to collapse of selective subsegments of the lung and is being increasingly used in management of refractory, localized bronchopleural fistulas.

COMPLICATIONS

• FOB is overall very safe, with a reported mortality of 0–0.013%.7,8

• Major complications (pneumothorax, pulmonary hemorrhage, or respiratory failure) occur in <1% of procedures.7

• After bronchoscopy, the patient may experience low-grade fever, cough, hypoxemia, sore throat, hoarseness, or low-grade hemoptysis.

• Pneumothorax occurs in ∼4% of patients after transbronchial lung biopsy,8 and is usually detected by postprocedure chest radiograph.

REFERENCES

1. Ernst A, Silvestri GA, Johnstone D. Interventional pulmonary procedures: guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest. 2003;123(5):1693–717.

2. Prakash UB, Offord KP, Stubbs SE. Bronchoscopy in North America: the ACCP Survey. Chest. 1991;100(6):1668–75.

3. Eagle KA, Brundage B, Chaitman B, et al. Guidelines for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 1996;93(6):1278–317.

4. Wahidi MM, Jain P, Jantz M, et al. American College of Chest Physicians consensus statement on the use of topical anesthesia, analgesia, and sedation during flexible bronchoscopy in adult patients. Chest. 2011;140(5):1342–50.

5. Matot I, Kramer MR. Sedation in outpatient bronchoscopy. Respir Med. 2000;94(12):1145–53.

6. Mehishi S, Raoof S, Mehta AC. Therapeutic flexible bronchoscopy. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 2001;11(4):657–90.

7. Jin F, Mu D, Chu D, et al. Severe complications of bronchoscopy. Respiration. 2008;76(4):429–33.

8. Pue CA, Pacht ER. Complications of fiberoptic bronchoscopy at a university hospital. Chest. 1995;107(2):430–2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree