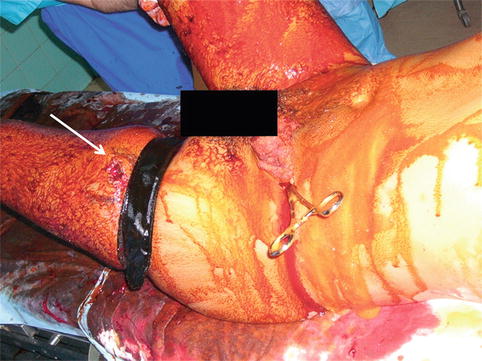

Fig. 22.1

A Special Operations Forces Tactical Tourniquet (SOFTT) controls hemorrhage from a popliteal artery injury (a), coupled with a plain radiograph showing a fracture of the supracondylar femur (b, white arrow), a pattern highly suggestive of a vascular injury (From Fox and Starnes [22])

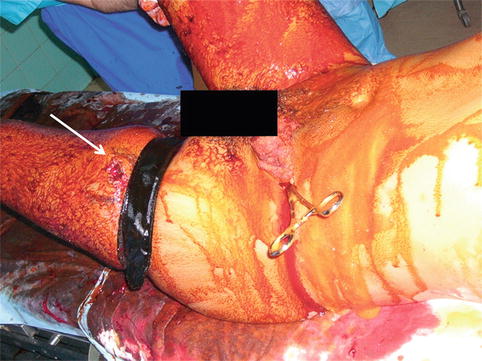

Fig. 22.2

The combat application tourniquet (CAT) is carefully loosened to evaluate a popliteal vascular injury. The Emergency Medical Tourniquet (EMT) was applied above the narrow field tourniquets. A medial approach is preferred (black line) (Courtesy of COL (ret). John F. Kragh, Jr, MD, San Antonio, TX; From Fox and Starnes [22])

Color-flow duplex (CFD) ultrasonography is an accurate noninvasive screening adjunct that can complement or sometimes be substituted for an arteriogram. This study can usually be obtained rapidly and used to detect occlusion, intimal flaps, and luminal defects. Bandages, open wounds, and orthopedic hardware may limit the utility of CFD in a trauma setting. CFD is highly operator dependent and has led many to prefer CTA as a noninvasive alternative of choice. Although ionizing radiation and nephrotoxicity are obvious disadvantages, these rapid multi-planar acquisitions allow for high-resolution three-dimensional reconstructions that can be superior to a catheter-based arteriogram. CTA has the advantage of imaging multiple extremities and the surrounding soft tissue simultaneously. CTA is also useful in surgical planning; however when an endovascular intervention is anticipated, the volume frequency and type of contrast agent to be administered should be discussed [11].

22.4 Operative Management

The first goal of the emergency operation is to control hemorrhage with close hemodynamic monitoring and judicious replacement of fresh warm blood products in equal ratios. The patient should have broad antibiotic coverage and be positioned supine on a fluoroscopic table with at least one uninjured limb prepped for a vein harvest.

Proximal control of hemorrhage is often accomplished by firm digital occlusion using an assistant’s gloved hand prepped directly into the bleeding wound bed with Betadine spray. This is followed by careful dissection proximal and distal to the site of injury. Balloon catheters may also tamponade hemorrhage when a tourniquet or manual pressure is not effective, but blind insertion of surgical instruments can be unproductive, or harmful, and is discouraged. Tourniquets are left in place until the anesthetist has sufficient time to resuscitate the patient. Proximal thigh injuries are best managed by division of the inguinal ligament or by the retroperitoneal approach with clamp control of the external iliac artery (Fig. 22.3). The medial approach is preferred over the posterior approach for femoropopliteal injuries. The approach in relation to the knee joint is directed by the level of the wound; however total division of muscular attachments at the knee is sometimes required to control hemorrhage of transected arteries and veins. Although often thrombosed at the time, the injured vessels must be found and ligated because they will re-bleed later after the patient is resuscitated. Retrograde advancement of a Fogarty catheter inserted from an uninjured distal site can also be used to locate the transected artery in a horrific wound that is no longer bleeding. A single bleeding tibial vessel can be ligated; however injury to the tibioperoneal trunk or multiple vessels should be repaired. Associated nerve, bone, and soft tissue injury are the essential determinants of limb salvage. When making a decision to amputate or salvage an extremity, consider the patients’ condition, extent of injury, and willingness to commit the patient to the necessary definitive orthopedic care and physical rehabilitation. No one situation or scoring system can replace the surgical judgment developed by an experienced team.

Fig. 22.3

Hemorrhage from a proximal left femoral artery gunshot wound is aptly controlled with a left retroperitoneal exposure and proximal clamping of the external iliac artery. The entrance wound (white arrow) is in the proximal lateral thigh

A primary end to end repair is preferred when lateral sutures cannot repair the injured vessel. Advantages of this repair include a single anastomosis and use of autologous tissue. Dividing nearby geniculate branches may gain some length in noncalcified vessels, but this repair should be both expedient and free of tension. Complete debridement of any disrupted tissue is an essential step of the repair, and sacrifices made to avoid an interposition conduit should be avoided.

If an interposition graft repair is required, the complexity and additional operative time required for vein harvest and interposition grafting should be appreciated, and the final operative plan and estimated time should be communicated early to the operative team. Saphenous vein taken from an uninjured limb including the arm is the preferred conduit for the reconstruction of lower extremity vascular injuries. However, in the author’s experience expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) prosthetic grafts placed in larger vessels with good muscle coverage have been used successfully. Systemic anticoagulation is generally avoided for trauma except for an isolated vascular injury in a non-coagulopathic patient without extensive soft tissue damage.

Ballistic injuries transmit kinetic energy and result in intimal damage well beyond the transected arterial segment. Therefore, one should carefully open vessels longitudinally and inspect the quality of the luminal surface and the arterial inflow relative to the mean arterial pressure. When necessary, a Fogarty embolectomy catheter should be carefully advanced as tourniquets and limited heparin dosing easily result in thrombus accumulation. Special precautions should include routine flushing of the graft, and native artery with heparinized saline to dislodge fibrin strands, and platelet debris. This is best done with a solution of Papaverine and warm heparinized saline. A well-spatulated four-quadrant, heel-to-toe anastomosis is the easiest method to teach and perform in difficult situations. Small Heifetz clips or bulldog clamps can also minimize potential clamp injuries of small vessels. There is documented value in repair of concomitant venous injuries to avoid the potential for early limb loss from venous hypertension or long-term disability from chronic edema. With combined arterial and venous injuries, arterial repair should precede venous repair to minimize further ischemic burden, unless the vein repair requires very little effort.

Shotgun or fragment injury produces large cavitary wounds; with severe disruption of the skin and loss of underlying muscle, it may be difficult to achieve suitable graft coverage. Greer and colleagues reported on The Walter Reed Army experience with combat-related graft ruptures of which 70 % were in the femoropopliteal region. A significant factor was the degree of muscle coverage in the face of a contaminated wound. Therefore, when confronted with this situation, a longer vein graft tunneled completely around the zone of injury should be chosen over a shorter inadequately covered vein interposition conduit [13]. External fixation positioning should not impede the planned operative exposure. Tunneling grafts and preservation of skin bridges are therefore important matters to discuss before fasciotomy incisions are made (Fig. 22.4). Devitalized tissue is excised and irrigated under low pressure, with careful evaluation of muscle tissue for viability. Injured nerve tissue should be tagged at both ends with monofilament suture. A lengthy and meticulous debridement at the outset is not usually necessary as these wounds look much better in a few days after subsequent washouts and vacuum dressings. Always maintain a low threshold for performing a four-compartment fasciotomy. This is usually performed first and the length of the incision may vary with the clinical scenario but an incomplete fasciotomy can be catastrophic. The application of vessel loops to prevent skin retraction and the use of negative pressure dressings have made primary closure more successful and eliminated the need for routine split-thickness skin grafts (Fig. 22.5).

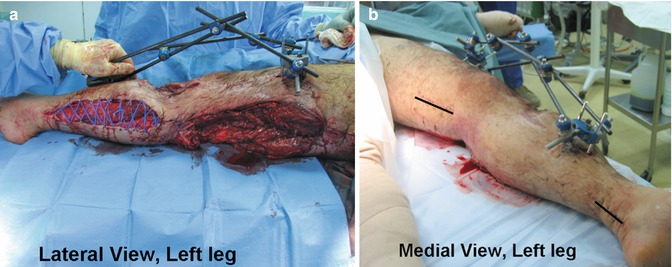

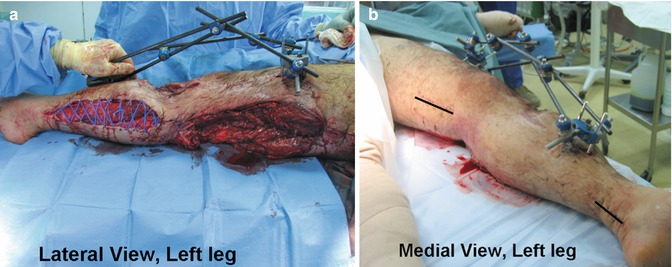

Fig. 22.4

A lower extremity fragment wound resulting in severe destruction of the popliteal and tibial vessels (a) was reconstructed with an above-knee popliteal to posterior tibial artery bypass using a reversed saphenous vein graft. Knee-spanning external fixation for this tibial plateau fracture can be applied quickly to stabilize the limb and permit excellent surgical exposure (black line) out of the injured region (b) (From Fox and Starnes [22])

Fig. 22.5

Negative pressure (vacuum) therapy has facilitated earlier closure of fasciotomy surgical sites (a) and other deep cavitary wounds of the lower extremity. A vacuum seal can be easily obtained despite the use of orthopedic hardware in this child (b)

22.5 Temporary Vascular Shunts

Temporary vascular shunts are effective damage control techniques that allow for delayed reconstruction and should be compared with the consequences of simple ligation. Temporary vascular shunts allow for perfusion during temporary delays needed for extremity fixation, patient transport, addressing more life-threatening injuries, or assessment of revascularization options including during vein harvest. Several high-quality papers have advanced its use during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. At the 2006 meeting of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, the Air Force demonstrated that shunts placed in proximal vascular injuries have acceptable (86 %) patency, and failure of distal shunts did not decrease limb viability [14]. In 2007, Taller and colleagues reported successful shunting with 96 % patency among casualties evacuated from a remote Navy Echelon II – Forward Resuscitative Surgical Suite (FRSS) based in the western province of Iraq. The mean shunt time was 5 h 48 min (range, 3:40–10:49), and the authors meticulously documented the time from shunt placement to casualty presentation at the level 3 surgical facilities in Baghdad or Balad, Iraq. These authors also validated the earlier experience of a US Navy forward surgical unit and concluded that complex combat injuries to proximal extremity vessels should be routinely shunted at forward-deployed Echelon II facilities as part of the resuscitative, damage control process [15].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree