Fig. 6.1

(a) Reverse Henry incision and brachial artery exposure. (b) Close-up of incision with nearby neurovascular structures. (c) Photograph of patient with reverse Henry incision. The carpal tunnel aspect is often included. A proximal incision lateral to the biceps is used for direct access to the brachial artery. The antecubital crease is crossed transversely, followed by a curvilinear incision over the wrist. The lacertus fibrosis (bicipital aponeurosis) is released at the elbow, followed by the mobile wad and forearm muscles. The medial flexor wad and digital flexors are also released. The dorsum of the forearm and carpal tunnel are also released if necessary

The muscles of the hand are then assessed and interossei and thenar decompression as necessary.

6.2.1 Step-by-Step Fasciotomy of the Upper Extremity (Fig. 6.1)

1.

Inscribe Henry incision of forearm.

2.

Include carpal tunnel aspect if necessary; center of wrist to space between middle and ring, favoring ring finger aspect.

3.

Proximal incision lateral to biceps for direct access to brachial artery joins incision from proximal repair; requires primary closure or protected VAC.

4.

Cross antecubital crease transversely; direction depending on proximal incision option.

5.

Curvilinear incision over wrist to create radial artery protective flap.

6.

Release lacertus fibrosis (bicipital aponeurosis) at elbow, between biceps tendon.

7.

Release mobile wad; brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis.

8.

Release medial flexor wad.

9.

Release superficial and deep digital flexors.

10.

Assess need for carpal tunnel and dorsal forearm release, often unnecessary.

11.

Release dorsum of forearm and carpal tunnel.

Final assessment prior to applying dressings includes a reassessment of proximal structures. The biceps and brachialis can be decompressed with a proximal extension of the fasciotomy over the medial biceps. Occasionally the triceps need to be released through a separate dorsal approach. Deltoid release is on a case by case basis.

There are several options for wound management, and, as of the writing of this chapter, vacuum-assisted wound management is one of the more frequently used in North American trauma centers. One must carefully protect the neurovascular structures prior to application, occasionally the carpal tunnel can be closed prior to dressing application.

6.3 Orthopedic Fixation in Combination with Vascular Repair

Skeletal fixation choices will also depend on time since injury, associated contamination, location of fracture as well as relation to vascular repair, and other injuries to the same patient. Vascular repair and fasciotomies are usually stabilized relative to the fracture or dislocation associated with the vascular injury. Fixation methods must allow access to the fasciotomy to allow for inspection and dressing changes. Subclavian and proximal brachial arterial injuries usually do not benefit skeletal fixation as fixation of the proximal humerus is complex and time consuming.

At the time of this writing, our preference for fasciotomy coverage and closure is early VAC dressings, delayed primary closure, and split thickness skin graft if necessary. Free tissue transfer is used if the upper extremity is deemed salvageable and fasciotomy position is concurrent with wounds of the arm or forearm [3].

6.4 Fasciotomy of the Thigh

Fasciotomies of the lower extremity in a civilian trauma practice are primarily indicated to treat conditions of the leg, usually associated with blunt or penetrating trauma affecting the extremity between knee and ankle. Most discussion on indications, anatomy, and technique centers on pathology affecting this area. The buttock, thigh, and foot require fascial release less often, and indications for release in some of these areas are evolving topics of discussion.

Fasciotomy of the buttock is rarely indicated in blunt trauma, occasionally suspected with both direct injury and developing signs such as decreasing sciatic function, observed directly. There are few cases described involving vascular injury to the area resulting in contained hemorrhage into muscle bellies or fascial planes that yield compartment syndrome-like symptoms. If encountered, it may be secondary to a named vessel hemorrhage related to a superior gluteal branch. Useful fasciotomies to this area can be performed through a Kocher-Langenbach approach.

The thigh rarely needs decompression because the anatomy provides significant space to contain moderate amounts of hemorrhage (Fig. 6.2). There are instances of direct vascular trauma, high-energy crush, prolonged entrapment, or extreme positioning. The thigh has three anatomic compartments, two of which can be decompressed through the same skin incision, after which the third is reevaluated for need of decompression. Upon deciding to release the fascia of the thigh, an anterior lateral incision of at least 20 cm is made over the anterolateral thigh with a slight lateral bias. The incision permits inspection of the quadriceps fascia which is then released.

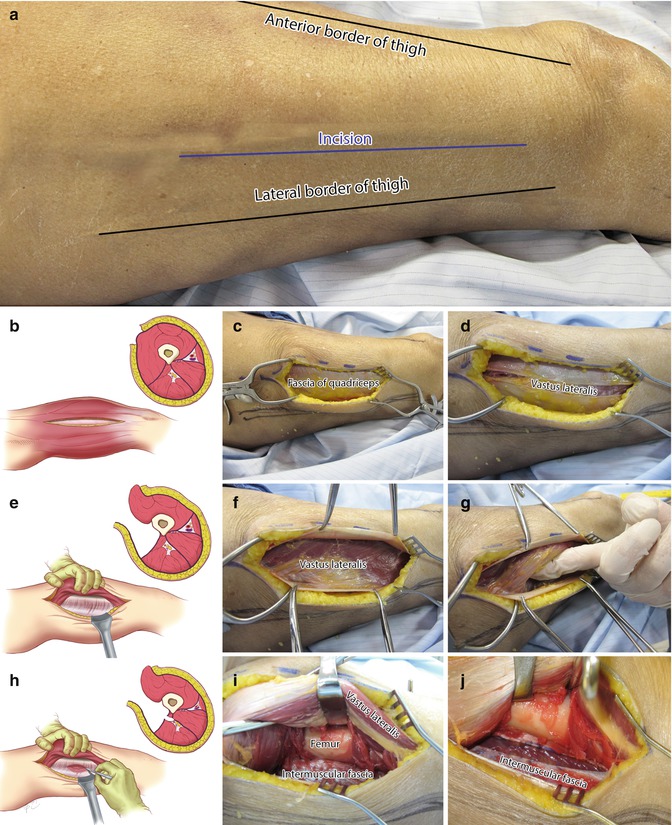

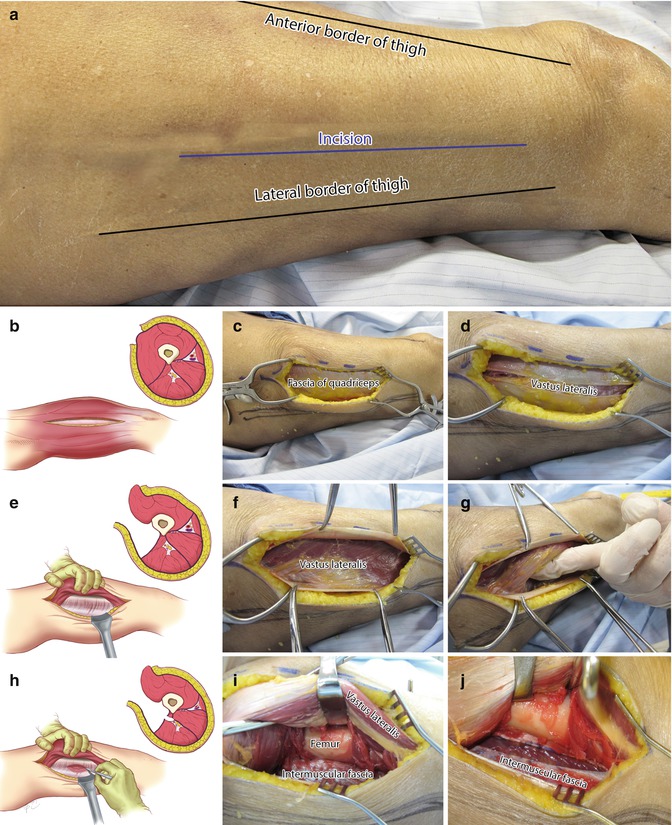

Fig. 6.2

Lateral thigh fasciotomy and key steps for release of intermuscular fascia (a–j). After making an incision midway between the anterior and lateral border of the thigh (b, c), the fascia of the quadriceps is incised and released (d). The vastus lateralis is rolled anteriorly to expose the intermuscular fascia (e–g). This fascia is then incised 1 cm from the femur in order to avoid the perforating vessels (h–j). The hamstrings are released and the medial compartment reassessed. The adductors may be released if necessary using a longitudinal 5 cm incision

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree