Failing Lower Extremity Bypass

NICHOLAS OSBORNE and PETER K. HENKE

Presentation

A 75-year-old man is seen for routine follow-up after undergoing reoperation on left femoral to below-knee popliteal bypass with reversed greater saphenous vein, which was done 6 months ago for rest pain. The patient had a prior femoral to above-knee popliteal bypass with prosthetic, and this had failed within 1 year. Past medical history includes diabetes, tobacco use times 30 years (and currently), hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Medications include aspirin, a beta-blocker, an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, and a multivitamin. The patient has no current symptoms and is ambulating more than half a mile without claudication. Physical examination shows a well-healed incision in his left groin and below-knee calf incision. The patient has a faintly palpable dorsalis pedis pulse with a biphasic Doppler signal. Ankle-brachial indices (ABIs) performed in the clinic prior to the visit demonstrate a decrease in his left (operative) leg of 0.61 from immediately post-op (0.86).

Differential Diagnosis

Although this patient is currently asymptomatic, they have an at-risk bypass graft. This early decrease in the ABIs suggests that there is a stenosis of the inflow, outflow, or bypass graft itself. The timing of the presentation correlates with the most common causes of graft failure. Within the first month following bypass, most bypass graft failures are due to technical problems or problems with conduit adequacy. These technical problems can range from anastomotic problems, persistent valve, or arteriovenous fistulae (especially in in situ grafts) and poor conduit. Between the period of 1 month and 2 years, failing bypasses are most likely due to intimal hyperplasia, but this may represent a technical problem such as an unrecognized sclerotic segment of vein, a frozen valve, or a stenosis of the inflow or outflow. Although long-segment stenoses are less likely, these can result from injury during vein harvest. After 1 to 2 years, the most common cause of bypass graft failure is progression of atherosclerotic disease of not only the inflow and outflow vessels but of the bypass graft itself.

Workup

All postoperative lower extremity bypass grafts should be followed with a standardized surveillance protocol; generally at first postoperative visit, then every 3 months for the first year, then biyearly, and then yearly. Recent studies of grafts followed with surveillance duplex have shown a primary assisted patency rate of 80% at 3 years. Although ABIs were not predictive of graft failure/revision, duplex ultrasonography (graft scans) has been correlated with improved patency rates. Graft stenoses may not manifest with dramatic changes in patient symptoms or changes in the ABI.

The patient’s ABI is 0.61 on the left with biphasic Doppler waveforms. This suggests that there is a stenosis that will require reintervention to maintain graft patency.

Diagnosis and Treatment

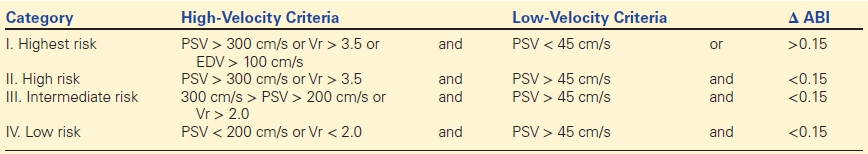

Duplex graft surveillance is a well-established technique proven to significantly improve graft patency and limb salvage by 30% to 50% over 5 years and decrease early graft thrombosis by more than 50%. The concept is that a hemodynamically significant stenosis in the graft can be found and treated before the patient becomes symptomatic secondary to a thrombosed graft. Salvage techniques such as graft thrombolysis and revision are much less successful than if treated electively. Most graft stenoses occur within the first 2 postoperative years, and thus, more frequent early scanning is recommended (about every 3 to 6 months for the first year, every 6 months for the second year, and then yearly). Graft duplex velocities increase at the region of stenosis, and comparison between the highest velocity and just proximal to the stenosis velocity is essential. Table 1 shows an established classification of at-risk bypass grafts using duplex and ABI criteria. In general, as the velocity exceeds 300 cm/s, the graft is considered threatened. Highest-risk grafts have a loss of energy associated with a drop in the velocity following the stenosis to below 45 cm/s.

TABLE 1. Vein Graft Velocities and Risk of Graft Failure

PSV, peak systolic velocity; EDV, end-diastolic velocity; Vr, velocity ratio.

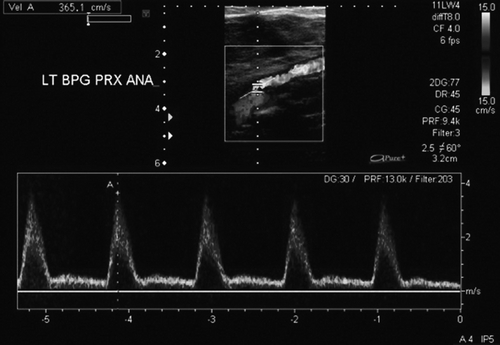

The patient underwent a duplex (graft scan), which showed a high-grade stenosis of the proximal anastomosis of 339 cm/s (Fig. 1). Early graft stenoses traditionally were treated with open surgical revision in the era prior to endovascular therapy. Currently, an endovascular approach can be attempted for a focal stenosis as first line.

FIGURE 1 Duplex ultrasound image showing high velocity in proximal vein graft. Note nice acoustic window, suggesting little turbulence.