Chapter 9 Evidence-Based Surgery

Critically Assessing Surgical Literature

What is the Purpose of the Study?

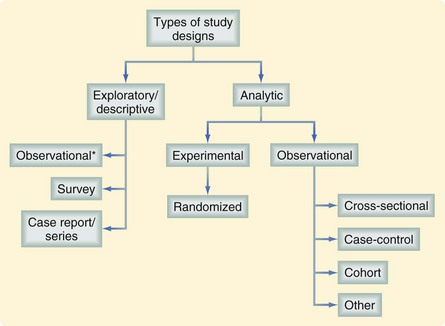

Assessing the value of a study requires an understanding of the investigator’s intended purpose. Most studies can be placed into one of two general categories, descriptive (or exploratory) and analytic (Fig. 9-1). Most descriptive studies should be considered hypothesis-generating rather than causality-focused whereas analytic studies test a prespecified hypothesis. A study’s purpose should drive the selection of study groups, outcomes of interest, data sources, study design, and analytic plan. Unfortunately, many studies fall short in linking study purpose and methodology; investigators may sometimes try to establish causality from descriptive studies. For example, in a study describing trends in the misdiagnosis of appendicitis during a time when there was increased use of diagnostic testing, an attempt to establish a causal link between these two findings (i.e., the trend in misdiagnosis was caused by the trend in diagnostic testing) would be overreaching the descriptive nature of the study.1 The intent of descriptive studies should be identifying possible associations and serving as an impetus for future investigations using more rigorous analytic approaches.

What is being Compared?

Misclassification

Stage migration, also known as the Will Rogers phenomenon, is a classic example of misclassification.2 Cancer stage has a well-defined relationship with long-term survival. Patients may be staged through clinical examination, radiographic assessment, invasive procedures, or pathologic tissue examination (the gold standard). Staging techniques other than pathology-based approaches may be inaccurate. It is not uncommon for higher accuracy staging modalities to be associated with higher observed survival rates when compared with lower accuracy methods (e.g., a clinical examination). Patients only assessed clinically might be understaged—categorized as early-stage cancer but actually with late-stage cancer. Survival rates for early- stage patients would then be worse than they really were because misclassified late-stage patients lower the group average. Similarly, if overstaged patients were considered with truly late-stage patients, survival would be better than in actuality. This phenomenon has been demonstrated in a study of lung cancer patients in which those who underwent pathologic staging had better 5-year survival rates compared with those who underwent clinical staging.3

Time-Varying Exposures

Time-varying (or time-dependent) exposures refer to predictors whose value may vary with time (e.g., smoking status, transplantation status). Failure to account for time-varying exposures in the analysis of an observational study may lead to biased results and incorrect conclusions. An example of potential bias arising from time-varying covariates is an analysis of heart transplantation survival data.4 The impact of heart transplantation on survival was assessed by comparing patients who received a transplant with those who did not. Although the initial analysis revealed a survival benefit associated with transplantation, the manner in which patients were grouped (treating transplantation as a fixed variable) led to bias in favor of transplanted patients.

Transplantation wait times are often long and many patients die while awaiting a donor organ; therefore, patients on the transplantation wait list, but who died a short time after being listed, did not have a chance to undergo transplantation. When the investigators retrospectively assigned patients to these two study groups (transplanted versus not transplanted), the patients who survived long enough to receive a new heart introduced selection bias in favor of transplantation, because their survival times were on average longer than in the nontransplantation group. In actuality, each subject’s exposure status (transplanted versus not transplanted) was time-dependent. While on the wait list and prior to transplantation, a subject could contribute survival time to the nontransplantation group; subsequent to transplantation, the same subject could then contribute survival time to the transplantation group. Reanalysis of the data evaluating exposure status in a time-dependent fashion revealed no association between transplantation and survival.5

What is the Outcome of Interest?

Patient-Reported Outcomes

PRO data are collected through the use of survey instruments. These instruments are composed of individual questions, statements, or tasks evaluated by a patient. PRO instruments use a clearly defined method for administration, data are collected using a standardized format, and the scoring, analysis, and interpretation of results should have been validated in the study population. In general, researchers are advised to use existing instruments to measure PROs (rather than creating their own) because the appropriate development of an instrument requires significant time, resources, testing, and validation before application.6 Knowing whether the chosen instrument has been validated in the population of interest is also essential when interpreting the results and should be questioned when reading a study reporting PROs.

Costs

There are several different methods for comparative health economic analyses. All methods consider the costs of care in terms of dollars, but differ in terms of how they quantify health benefit. A cost-benefit analysis quantifies health benefit in terms of dollars. Although easy to compare and interpret such results, the great challenge with this approach is assigning a dollar value to a life or a specific health outcome. A cost-utility analysis quantifies health benefits in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). Utilities are a measure of overall quality of life, usually scaled between 0 and 1, with 1 being perfect health, and are ascertained using a visual analogue scale, the time trade-off, or standard gamble techniques.7 Utilities are multiplied by survival time to determine QALYs. When this outcome metric is evaluated as a cost/QALY, it is readily comparable between interventions. An intervention with an associated cost/QALY of $50,000 or less has typically been considered cost-effective. In the original Medicare law that included dialysis as a publicly funded treatment, $50,000 was determined to be the cost of dialysis. However, there is ongoing debate about the validity of this metric and a range of costs/QALY of $20,000 to $100,000 has been proposed as more reasonable.8 Cost-effectiveness analyses measure health benefit in terms of an outcome metric called the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), which is the difference in costs between two competing therapeutic options divided by the difference in health outcome. If the ICER comparing a treatment with a standard reveals that it is more expensive and less efficacious, it is considered to be dominated by the standard and not favored, whereas a less expensive and more efficacious treatment dominates the standard and is favored. Circumstances in which an intervention is more expensive and efficacious or less expensive and efficacious represent a trade-off.

Surrogate End Points

Interest in surrogate end points has emerged because definitive clinical outcomes may be difficult to assess secondary to the infrequency of a chosen clinical end point, the cost of ascertainment, or a long lag time to development. Surrogate end points are commonly used in studies of new pharmaceutical interventions when efficient data gathering about treatment effect is essential to move a product to the marketplace rapidly.9 The true clinical benefits of an intervention may take years to recognize, and it may be desirable to identify an intermediate outcome that could serve as a surrogate for the actual clinical effect. Unfortunately, the problem with using surrogate end points is that an intervention may influence an outcome through various, and potentially unintended or unanticipated, pathways.

A classic example illustrating the dangers of using surrogate end points was the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial.10 This study hypothesized that the incidence of sudden cardiac death could be reduced through the administration of flecainide or encainide. These drugs became popular because they had been designed to reduce the rate of ventricular ectopy, a common rhythm aberrancy thought to cause sudden cardiac death. Although these drugs had been shown to reduce ventricular ectopy, when mortality (a clinical, nonsurrogate end point) was measured in this trial, administration of these drugs was found to result in a threefold increase in the rate of death. Suppression of ventricular ectopy was therefore a poor surrogate for the intended clinical impact (improved survival) of these agents.

When evaluating a study, the reader must not only ask whether the selected outcome can answer the research question, but also whether that outcome is a meaningful clinical end point or simply a more easily measured surrogate. Criteria for validating a surrogate end point have been proposed—the surrogate end point should be correlated with the clinical end point of interest and fully capture the net effect of the intervention on the end point of interest.9 For example, with stage III colon cancer, there was interest in using adjuvant chemotherapy to improve survival. Disease-free survival was proposed as a surrogate for overall survival. Clearly, these two end points are correlated, satisfying the first criterion. Using meta-analysis, adjuvant chemotherapy was shown to result in similar relative improvement in both disease-free and overall survival.9 In other words, disease-free survival fully captured the net effect of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer, suggesting that it might be a valid surrogate for assessing overall survival benefit. Unless a chosen surrogate outcome has been validated and vetted in other surgical studies, the results and conclusions should be interpreted with caution.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree