Chapter 22 Evidence-Based Summary of Guidelines from the American Venous Forum and the Society for Vascular Surgery

Chronic venous disorders are among the world’s oldest afflictions and are responsible for substantial socioeconomic morbidity in the Western world. Varicose veins are the most common clinical manifestation of chronic venous disease, occurring in one fourth to one third of Western adult populations,1,2 while severe chronic venous insufficiency with skin changes and ulceration is present in 2% to 5% of Western populations.3 There have been many technological advances in the management of venous disease over the past decade, and many of these have had substantial benefits for afflicted patients. Unfortunately, many of these treatments are quite costly and are often approved, marketed, and adopted by clinicians without solid evidence supporting their use.

Although the current federal regulatory processes are effective in encouraging the development of new technology and do provide some mechanism for ensuring safety, they do not favor proof of clinically relevant efficacy.4,5 It is therefore becoming increasingly important for the clinician to have the skills to evaluate the clinical evidence and recommend the best treatment for their patients. The American Venous Forum has taken the lead in providing the clinical data clinicians require in caring for patients with venous disease and have published, together with the Society for Vascular Surgery, the most up-to-date practice guidelines for the care of patients with venous disorders.6

Evidence-Based Medicine and Practice Guidelines

Evidence-based medicine is perhaps best defined as “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of the current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients.”7 This specifically involves integrating clinical expertise, the patient’s individual values and preferences, and the best available clinical evidence. Older approaches to evaluating clinical evidence relied primarily on a hierarchy of study methodology, a system that provides little guidance to physicians in daily practice. While randomized clinical trials are usually less prone to bias and are less likely to lead to false-positive conclusions, it is unrealistic to expect data from rigorously conducted trials to guide every clinical question that arises. Furthermore, they may not be appropriate for all diseases and interventions.8 Randomized trials are difficult to justify when interventions are clearly harmful or show a large beneficial treatment effect (risk ratio <0.4) in observational studies or when the treatment effect is so small (risk ratios 0.9 to 1.0) that sample size requirements preclude adequately powered randomized trials. Perhaps most importantly, clinicians are less interested in the precise study methodology than they are in reliable estimates of the benefits and harms associated with a therapy.9 For high-quality evidence, the effects of therapy are precise, and further research is unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. In contrast, the estimated effect provided by poor-quality evidence may be unclear and subject to change as better-quality evidence becomes available.

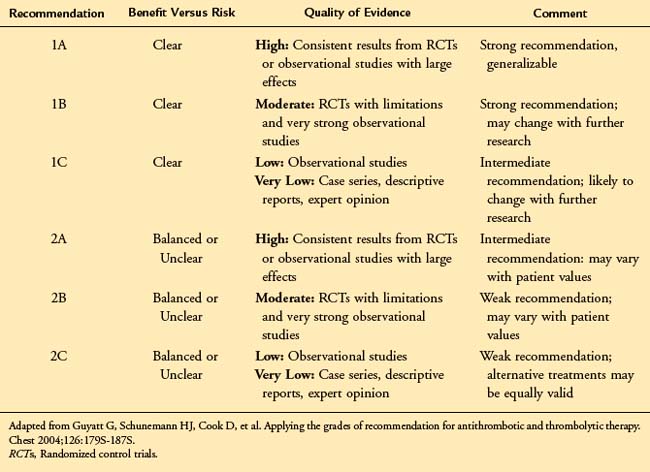

Current approaches to the evaluation of clinical evidence account for these concerns and are based largely on an assessment of the estimate of effect (beneficial or ill) associated with a treatment. The approach developed by the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) working group9 has been adopted by the American Venous Forum in developing practice guidelines.9 According to this system, there are two components to any treatment recommendation—the first a designation of the strength of the recommendation (1 or 2) based upon the degree of confidence that the recommendation will do more good than harm, the second an evaluation of the strength of the evidence (A to D) based upon the confidence that the estimate of effect is correct. (Table 22-1).

In accordance with the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines for the antithrombotic treatment of venous thromboembolic disease,10 the American Venous Forum has adopted the language of “recommending” the use of strong Grade 1 guidelines and “suggesting” the use of weaker Grade 2 guidelines. These guidelines should be viewed as a summary of the best available clinical evidence to guide the management of patients with chronic venous disease. However, consistent with the goals of evidence-based medicine, they are subject to the physician’s clinical judgment, resources, and expertise and the patient’s individual values and preferences. They should not be interpreted as a rigid “standard of care.” The key elements of the evidence-based guidelines are outlined in Table 22-2.

![]() TABLE 22–2 Key Treatment Recommendations for Chronic Venous Disease

TABLE 22–2 Key Treatment Recommendations for Chronic Venous Disease

| Guideline | Grade of Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis of Chronic Venous Disease | |

| We recommend initial clinical evaluation including a thorough history, focusing on the underlying etiology (congenital, primary, or secondary), symptoms, and risk factors for venous disease. | 1A |

| We recommend duplex ultrasonography, including an evaluation of reflux in the upright position, as the initial diagnostic test in patients with CVD. | 1A |

| We recommend threshold values for reflux of >500 ms for reflux in the saphenous, deep femoral, tibial, and perforating veins and >1 s in the femoral and popliteal veins. | 1B |

| We recommend adjunctive studies including plethysmography, CT/MR venography, and IVUS in selected patients in whom the pathophysiology is incompletely defined by ultrasound or in whom a surgical or endovenous intervention is planned. | 1B |

| Management of C1-C3 Chronic Venous Disease | |

| We suggest the use of venoactive drugs such as horse chestnut seed extract for amelioration of the symptoms of pain and swelling. | 2B |

| We suggest the use of 20–30 mm Hg compression stockings for patients with symptomatic varicose veins who are not candidates for superficial venous intervention. | 2C |

| We recommend stripping or ablation of the saphenous vein in preference to compression stockings in patients who are suitable candidates. | 1B |

| We recommend endothermal venous ablation in preference to high ligation and stripping or foam sclerotherapy for the management of saphenous vein incompetence. | 1B |

| We recommend sclerotherapy for the treatment of reticular veins, telangiectasias, and recurrent varicose veins. | 1B |

| We recommend phlebectomy over sclerotherapy for the treatment of tributary varicosities once axial reflux has been addressed. | 1B |

| We recommend against the treatment of incompetent perforating veins in patients with C2 CVD. | 1B |

| Management of C4-C6 Chronic Venous Disease | |

| We recommend compression therapy for the treatment of venous leg ulcers. | 1A |

| We suggest pentoxifylline as an adjunct for the healing of venous leg ulcers. | 2B |

| We recommend sharp debridement of venous ulcers associated with significant slough and nonviable tissue. | 1C |

| Depending on the specific agent, specialized wound dressings can be only weakly suggested. | 2 B/C |

| We recommend the treatment of saphenous incompetence to reduce the recurrence of venous leg ulcers. | 1A |

| We suggest the treatment of pathologic perforating veins—defined as incompetent perforating veins ≥3.5 mm in diameter with outward flow ≥500 ms in duration and located beneath a healed or open venous ulcer. | 2B |

| The benefit of deep venous valvular reconstruction is poorly established and is suggested only in centers with substantial experience and after failure of treatments supported by more substantial data. | 2C |

CT/MR, Computed tomography/magnetic resonance; CVD, chronic venous disease; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound.

Evidence-Based Management of Venous Disease

Evaluation and Follow-up of the Patient with Chronic Venous Disease

Evaluation of the patient with venous disease should include a thorough history, focusing on the underlying etiology (congenital, primary, or secondary), symptoms, and risk factors for venous disease (Grade 1A). This should include an assessment of the degree of disability and effect on the patient’s quality of life. Physical examination should focus on specific features of venous disease and exclusion of other etiologies of the patient’s signs and symptoms. In clinical practice, every patient should be characterized using both the basic CEAP classification and the Venous Clinical Severity Score (VCSS).11,12

For research investigations, the use of patient-important outcomes is strongly recommended, while the use of technical or surrogate outcome measures should be restricted to early feasibility studies. Several disease-specific quality of life measures are available for this purpose.13–15

Treatment of Mild (C2-C3) Chronic Venous Disease

Compression Therapy

Despite the absence of methodologically sound data, compression stockings are often considered first-line therapy for mild to moderate chronic venous disorders. The majority of comparative studies of compression stockings have evaluated surrogate hemodynamic parameters rather than patient-important outcomes, and it does appear that stockings improve a variety of hemodynamic measurements.16 However, the clinical benefits are less clear. Comparisons to placebo are very limited but do suggest some improvement in symptoms with the use of compression stockings.16 Others have reported improvement in up to one third of patients with compression stockings.17 Definitive data regarding the optimal degree of compression are lacking. However, symptomatic improvement is clearly less than after surgical treatment of varicose veins,17 and the authors of one systematic review concluded that the benefits of compression as a first-line treatment are limited.16 Although 20 to 30 mm Hg compression stockings are suggested for patients with symptomatic varicose veins (Grade 2C), the American Venous Forum recommends against their use as the primary treatment in patients who are candidates for superficial venous intervention (Grade 1B). Compression stockings should be considered only after a thorough history and measurement of the ankle-brachial index to exclude arterial disease and should be fitted by appropriately trained personnel.16

Pharmacologic Therapy

Phlebotonic agents have been used to address many of the symptoms of chronic venous disorders, including leg pain, swelling, and pruritus. These include a heterogeneous group of plant extracts (rutosides, hidrosmine, diosmine, and others) as well as synthetic drugs with similar properties. A systematic review of 44 randomized, placebo-controlled trials evaluating oral phlebotonics suggested efficacy for some signs such as edema, although the global evidence for their efficacy was insufficient to recommend routine use.18 While other preparations are available abroad, horse chestnut seed extract is the most studied preparation available in the United States. A systematic review of 17 randomized, controlled trials of horse chestnut seed extract suggests significant benefits with respect to leg pain, edema, and pruritus.19 Two of these trials demonstrated similar improvements with horse chestnut seed extract and compression. Although the data are somewhat heterogeneous and the consequences of long-term use are poorly documented, there is at least a suggestion that the venoactive drugs may have some benefit in patients with C2-C3 disease (Grade 2B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree