Evaluation of Respiratory Impairment and Disability

INTRODUCTION

Management of a patient with chronic lung disease does not end with its treatment. Those with chronic pulmonary disorders need additional assistance and guidance on issues related to respiratory impairment, including causation or attribution; apportionment; eligibility for, and access to, various compensation systems; workplace modifications or removal from the workplace; and vocational and other forms of rehabilitation. Unfortunately, most physicians avoid providing these services, often with disastrous socioeconomic and medical consequences for the patient.

Multiple reasons underlie the general attitude of physician reluctance in addressing impairment. These include a fear and poor understanding of the legal system as it relates to work-related diseases, pervasive confusion about various compensation systems, a mistaken notion that those who seek impairment assistance are usually malingerers, lack of training in impairment evaluation, and a desire to avoid uncompensated efforts in the context of an already burdensome clinical schedule. This chapter provides an understanding of this complex, but ignored, area in clinical pulmonary medicine.

TERMINOLOGY

This field of impairment and disability evaluation bridges medicine and law; hence, its terminology, drawn from both fields, can be confusing. The terms, impairment and disability, are often used interchangeably, but they are not synonymous. In 1980, the World Health Organization issued a statement defining impairment as, “any loss or abnormality of psychological, physiologic, or anatomical structure or function,” and disability as, “any restriction or lack, resulting from impairment, of ability to perform an activity within the range considered normal for a human being.”1 The resulting social and occupational disadvantage is designated as handicap.

For a patient with chronic lung disease, the goal of respiratory impairment evaluation is objective measurement of the extent of loss of function, primarily through application of pulmonary function or exercise testing. The physician plays a key role in impairment evaluation. On the other hand, the impact of the respiratory impairment on a person’s ability to perform day-to-day activities is called disability, which is typically determined through application of administrative and legal instruments by experts in these areas. The experts not only rely upon the evaluation of impairment provided by the physician, but also take into consideration other social and legal issues, as well as the energy requirements of the occupation. Impairment may occur without disability, and disability may occur without measurable impairment. Furthermore, two individuals with exactly the same respiratory impairment may suffer differing impacts on their lives, and consequently, have different levels of disability.

Respiratory impairment may be temporary or permanent. In contrast to temporary impairment, permanent impairment is not expected to improve with time or treatment. Disability may be partial or total. Total disability implies that an individual is unable to perform any work of the kind that he or she has the skills and qualifications to perform. Partial disability implies that an individual is able to perform some, but not all, of the work.

Causation or attribution refers to whether an exposure has been a “substantial” contributing factor in either causing or exacerbating lung disease. The level of certainty required in determining causation for occupational lung disease is different from the usual standard of 95% certainty used in medical research. The commonly accepted standard of certainty for occupational cases is that the illness is substantially caused, or exacerbated by, an occupational exposure on a “more probable than not” basis, or a level of certainty greater than 50%.

Apportionment describes the relative contribution of multiple factors to the total respiratory impairment. For instance, both chronic inhalational asbestos exposure and cigarette smoking may be contributory factors to lung cancer. From a scientific perspective, it is usually difficult, if not impossible, to “apportion” the relative roles of multiple exposures in causation of an individual’s complex, multifactorial disease. Physicians are often asked to state their opinion on apportionment in the context of the body of available knowledge in that area.

IMPAIRMENT SYSTEMS COMMONLY USED IN THE UNITED STATES

Patients seeking an impairment evaluation can be usually classified into three general types: (1) Those with advanced lung disease who apply for disability benefits under the Social Security Impairment program, (2) those with work-related lung disease who apply under the Workers’ Compensation System (but also other programs, such as the Black Lung Benefits Act for coal mine workers), and (3) those who develop lung disease while working for certain employers, such as the Veterans Administration. The most commonly used impairment guidelines in the United States are the Social Security Impairment program and the Workers’ Compensation System. Each are discussed in greater detail in subsequent sections.

SOCIAL SECURITY IMPAIRMENT

SOCIAL SECURITY IMPAIRMENT

The US Social Security Administration incorporates two programs that provide financial and rehabilitative benefits to disabled individuals. Both require objective demonstration of disability using medical standards set forth in the Social Security Act.

The first program is orchestrated through Title II of the Act, known as Social Security Disability Insurance. The program is available to individuals who are insured as a result of their contributions to the Social Security trust fund (through federal taxes paid on employment earnings during their work careers). The second is orchestrated through Title XVI of the Act, known as supplemental security income, or SSI. This program is available to disabled individuals who have limited income or resources and who are not covered by contributions to the Social Security trust fund. For adults, the definition of disability is the same whether application for benefits is made under Title II or Title XVI of the Social Security Act. The Social Security Administration defines disability as, “the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment(s) which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.” The methods used for disability evaluation under Social Security are important for the physician to understand for two reasons: (1) Disability designation under Social Security is a common and important source of financial support for many patients who are under the care of pulmonary physicians and (2) the pulmonary physician often takes an active role in helping determine eligibility under this program.

Evaluation of disability under Social Security is a staged process, beginning with application to a local Social Security field office or the Office of Disability Determination Services (DDS). The Office of DDS gathers objective medical information primarily from the treating physician, who is the preferred source of medical evaluation. If the available information is insufficient to make a determination of disability, the DDS may purchase additional testing and/or request examination from a consultant, such as a pulmonary physician.

The Social Security Administration has decided that certain specific impairments of each major body system are severe enough to prevent a person from engaging in any gainful employment and, therefore, serve as prima facie evidence that disability exists. These impairments have been codified as the Listings of Impairments.2 Listings under the respiratory system include specific categories of disease severity, including chronic respiratory disorders; asthma; cystic fibrosis; pneumoconiosis; bronchiectasis; mycobacterial, mycotic, and other chronic persistent infections of the lung; cor pulmonale due to chronic pulmonary vascular hypertension; sleep-related breathing disorders; and lung transplant.

If a claimant cannot meet the severity criteria of the Listings, the claimant may still receive an award of benefits by presenting pertinent medical information to the DDS. An initial judgment may then be made by the DDS, but the claimant has the right to challenge an unfavorable decision and to have it reviewed by other members of the DDS staff. If the decision is still unfavorable, the claimant may appeal to the Office of Hearings and Appeals for review by an administrative law judge, who may request expert physician testimony before making a decision. Once again, the claimant may request that an unfavorable decision be reviewed by an appeals council.

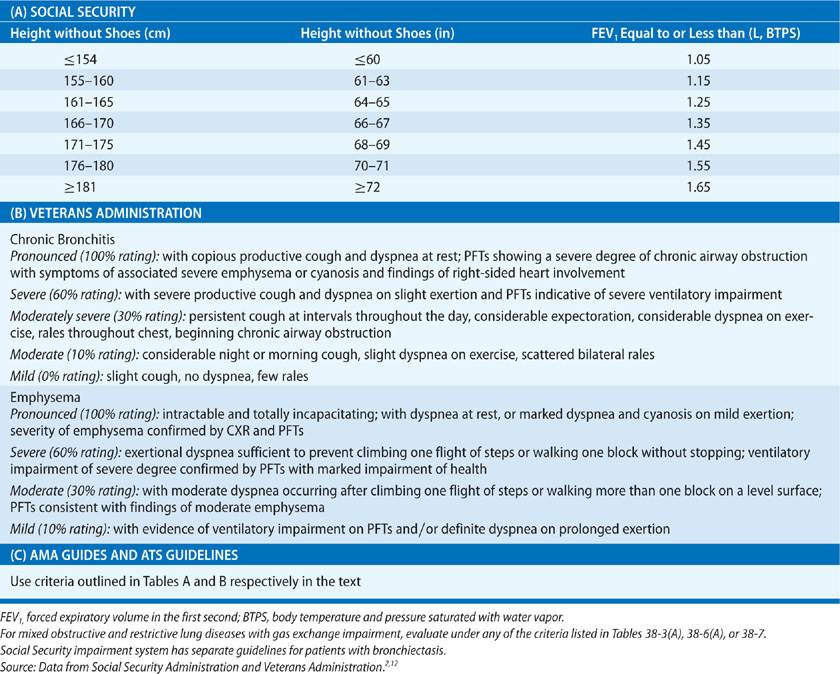

The Social Security program has some unusual requirements that distinguish it from other compensation programs: (1) The program requires a “hard copy” of the volume–time curve of a recent spirogram obtained following administration of inhaled bronchodilator when obstruction is present. (2) The program incorporates arbitrary, height-specific cut points for spirometric lung function for deciding impairment status; these cut points are not determined by race, ethnicity, age, or gender. (3) The program accepts an arterial blood gas measured during steady-state submaximal exercise at a work rate of 5 metabolic equivalents (METs) for rating impairment in gas exchange. (4) The program denotes the patient as either impaired or not impaired, rather than specifying a percent impairment. In this setting of binary categorization, those considered impaired under Social Security criteria are expected to have a level of impairment sufficient to prevent working for a period of 1 year or longer. (5) Unlike Workers’ Compensation programs, the Social Security program does not focus on occupational causation. The sole criterion for granting benefits is whether or not the claimant is able to participate in gainful employment. (6) The Social Security program also takes into account impairment from coexisting nonpulmonary conditions, such as substance abuse.

A major revision to the Social Security impairment criteria was proposed in February 2013.3 Although the revision has not yet been approved, it is expected that the program will drop its requirements for hard copy spirometric tracings, add age and gender to the spirometric criteria, and add height and gender to the diffusing capacity criteria. If approved, it is also expected to be the first major impairment program to accept graphical printouts of pulse oximetry on room air at rest or after a 6-minute walk test for evaluating gas exchange impairment.

WORKERS’ COMPENSATION SYSTEM

WORKERS’ COMPENSATION SYSTEM

The Workers’ Compensation system is a “no-fault” system of medical care and disability insurance in which private insurers or self-insured employers pay benefits to an employee sustaining an injury or illness due to workplace exposure. Under Workers’ Compensation rules, workers cannot sue their employer for injury or illness.

The rules for the Workers’ Compensation system vary from one state to another, but they usually follow one of the six editions of the American Medical Association (AMA) Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment.4 The various editions of the AMA Guides contain markedly different sets of recommendations on impairment evaluation, so one must choose the right edition for the purpose. Use of the wrong edition may result in an erroneous impairment rating. While other guidelines are available on the Internet without charge, use of web-based AMA Guides carries a fee.

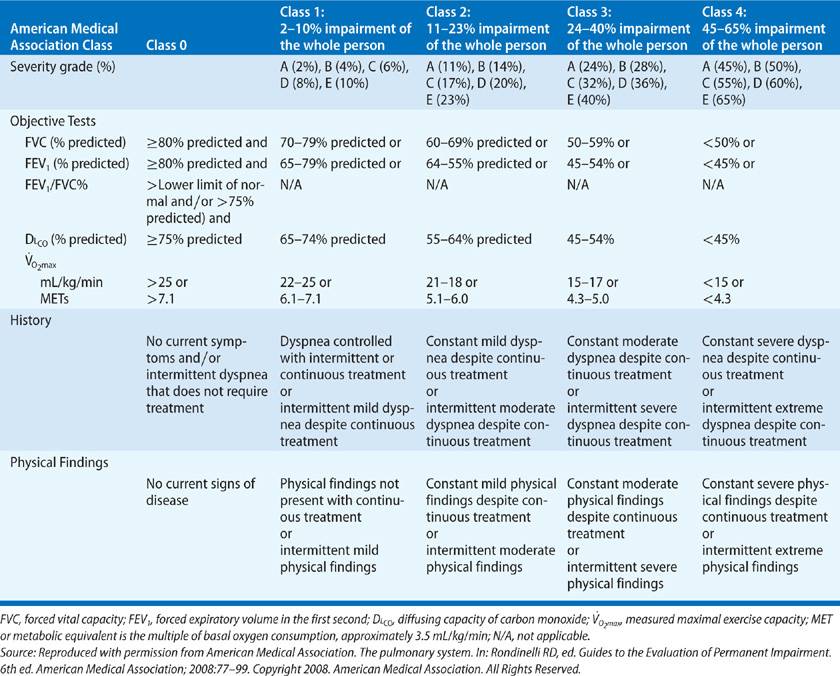

The sixth edition of the AMA Guides uses a standardized grid that incorporates five classes of impairment severity.4 The grids incorporate objective, test-based key criteria for defining the impairment class, along with other criteria for fine-tuning the severity grade within a given class. Among the various objective tests, the most severely affected test result is used to define the impairment class.

Although the American Thoracic Society (ATS) has also developed consensus guidelines for rating impairment from chronic respiratory conditions and asthma,5,6 these guidelines may not be accepted by a specific compensation program. While the AMA Guides generally follow the ATS schema, there exist substantial differences between the two guidelines.

FIVE GENERAL STEPS FOR IMPAIRMENT RATING

Five steps constitute the process of completing a respiratory impairment evaluation.

The first step is confirmation of the diagnosis of lung disease. Because of the medicolegal nature of the evaluation, the physician should have greater certainty of the medical diagnosis than is sometimes used in clinical practice. In other words, objective confirmation of the diagnosis is preferable.

The second step is defining maximal medical improvement (MMI). MMI occurs at the point when, following maximal therapy, no further clinical or physiologic improvement is expected to occur (although deterioration might). If therapy has not been maximized, the physician should either delay impairment evaluation or give a temporary rating. A permanent impairment evaluation should be performed only at, or after, MMI has been reached.

The third step is identifying the correct guideline for rating impairment. As discussed previously, several compensation systems exist, each with its own unique guideline. Therefore, identification of the compensation system for which the patient is eligible is essential, and the evaluating physician must be familiar with the specific guideline to be used. Of course, some patients may be eligible for more than one compensation program and may apply for more than one program contemporaneously.

The fourth step is to supplement the history and physical examination findings with appropriate objective tests. Performance of these tests should strictly adhere to standards of the ATS.7–10

The fifth and final step requires writing a comprehensive report of the patient’s history, physical examination, and review of objective tests. The assessment should provide clear and accurate answers, in lay terms, to the questions asked. The evaluation should state the diagnosis and whether MMI has been reached, and it should make note of the presence and degree of respiratory impairment. The specific impairment scheme used, including the specific page and table of the guideline used, should be referenced. In work-related respiratory disorders, causation, apportionment, and work restrictions should also be addressed, as requested.

GENERAL APPROACH FOR EVALUATING RESPIRATORY IMPAIRMENT

After determining patient eligibility for a specific compensation system, as described previously, the physician gathers data that is relevant to rating respiratory impairment. In general, impairment criteria are based upon history, physical examination, and objective test results.

The medical history focuses on detailed past and present occupational history, tobacco use and environmental exposures, presence and severity of respiratory symptoms, such as dyspnea, cough, sputum production, and wheezing, and medication history. Relevant features in the physical examination include breathing pattern, shape of chest wall, adventitious lung sounds, cyanosis, digital clubbing, and evidence of cor pulmonale.

RESTING PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTS

RESTING PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTS

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) (Chapter 33) are the cornerstone for rating respiratory impairment and should be performed according to the most recent ATS standards.7–10 Spirometry and diffusing capacity are the key PFTs for assessing respiratory impairment for chronic respiratory conditions. Postbronchodilator spirometry is used when airflow limitation is present. Methacholine challenge tests are used for rating impairment for asthma under the AMA Guides.4

Resting and exercise-related hypoxemia, derived from arterial blood gas results and adjusted for altitude and arterial PCO2 level, may be used under the Social Security impairment system to classify gas exchange abnormalities. However, arterial blood gas sampling needs to be repeated within 3 weeks to 6 months of the first sample.3 Although the presence of hypoxemia was previously used to rate impairment as severe under the fifth edition of the AMA Guides, the sixth edition does not include hypoxemia in the rating of respiratory impairment since it is considered invasive and difficult to standardize.4

Adjustment of PFTs for race, ethnicity, and gender is recommended by most impairment guidelines, with the notable exception of the Social Security impairment system, which currently uses uniform height-specific cut points for all individuals, irrespective of race, ethnicity, and gender.2 Thus, under this system, older women are more likely to be rated as disabled than are younger men.

According to the sixth edition of the AMA Guides, specific NHANES III reference standards for spirometry should be used for Caucasian Americans, Mexican Americans, and African Americans.4,11 For the remaining population subgroups, no clear guidelines are provided. Corrected single-breath carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO) is used under the AMA Guides, ATS guidelines, and Social Security Impairment guidelines for impairment rating, but it is not used under the Veterans Administration guidelines. Crapo’s reference standards for DLCO are used for comparison with measured values.

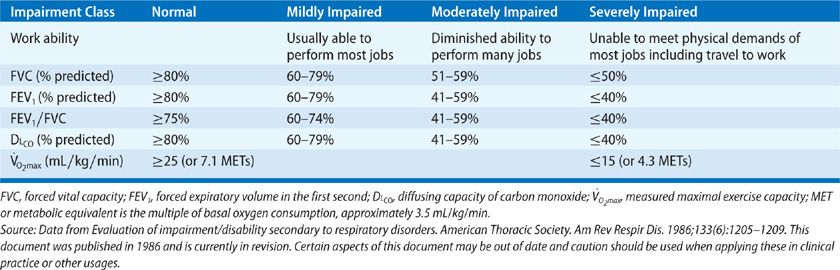

The cut points for impairment classification, as suggested by the various impairment guidelines (Tables 38-1–38-3) are set arbitrarily and may differ from those recommended for assessing degree of lung disease severity by other professional organizations, such as the 2005 ATS statement8 or by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD).13 Some investigators have suggested that lung function thresholds should be expressed as a z-score, which converts a raw measurement on a test to a standardized score expressed in units of standard deviations.14,15 This strategy, although scientifically valid, is not currently used for impairment evaluation.

Methacholine bronchoprovocation tests are useful for assessing bronchial hyperresponsiveness and in rating impairment from asthma under the AMA Guide and ATS guidelines (Tables 38-1 and 38-2).4,6 The methacholine PC20 (provocative concentration of methacholine, expressed as mg/mL that results in at least 20% drop in FEV1 compared to the pretest baseline) is a key parameter for rating asthma impairment under the sixth edition of the AMA Guides.4 The performance of methacholine bronchoprovocation tests should also strictly adhere to the ATS guidelines.16

TABLE 38-1 Classification of Respiratory Impairment from Chronic Lung Diseases, Using the Sixth Edition of the American Medical Association (AMA) Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment

TABLE 38-3 Impairment Rating Guidelines for Chronic Obstructive Lung Diseases using the Social Security, Veterans Administration, American Medical Association (AMA) Guides, and American Thoracic Society (ATS) Guidelines

EXERCISE TESTS

EXERCISE TESTS

Maximal cardiopulmonary exercise tests are difficult to perform due to need for specialized equipment and trained personnel, are expensive and not readily available, and carry a risk to the patient. Test performance should strictly adhere to the ATS guidelines.17 Clear agreement on the role of exercise tests in the evaluation of respiratory impairment is lacking. Generally, in cases in which subjective dyspnea is disproportionate to the resting PFT results, or when PFTs are difficult to interpret because of submaximal performance, cardiopulmonary exercise tests may be considered. Such tests may also help identify unanticipated coexisting conditions, such as cardiovascular or pulmonary vascular disease, as the cause of exercise limitation.

Exercise testing may also be useful in determining whether an individual can perform a specific job with a known energy requirement. Under the ATS guidelines, the estimation of impairment from oxygen consumption at peak exercise (![]() O2peak) is based on the widely held, but untested, assumptions that a worker involved in manual labor can comfortably work at 40% of

O2peak) is based on the widely held, but untested, assumptions that a worker involved in manual labor can comfortably work at 40% of ![]() O2peak (corresponding to lower limit of generally accepted normal values for anaerobic threshold) for prolonged periods,5 and that

O2peak (corresponding to lower limit of generally accepted normal values for anaerobic threshold) for prolonged periods,5 and that ![]() O2 requirements can be assigned to specific occupations. Individuals whose

O2 requirements can be assigned to specific occupations. Individuals whose ![]() O2peak is ≤15 mL/kg/min would be uncomfortable performing most jobs because they would find it difficult to travel back and forth to their place of employment (Table 38-2).5 Unfortunately, data on

O2peak is ≤15 mL/kg/min would be uncomfortable performing most jobs because they would find it difficult to travel back and forth to their place of employment (Table 38-2).5 Unfortunately, data on ![]() O2 requirements of most jobs in modern workplaces are not currently available. Furthermore, jobs with the same title may vary considerably in their

O2 requirements of most jobs in modern workplaces are not currently available. Furthermore, jobs with the same title may vary considerably in their ![]() O2 requirements from one work site to another.

O2 requirements from one work site to another.

Submaximal exercise tests at a workload of approximately 17 mL O2/kg/min (5 METs) or less of exercise can be performed at steady state to obtain arterial blood gases, which are then used to evaluate impairment of gas exchange under the Social Security impairment system when criteria for neither obstructive nor restrictive disorders are met. Use of submaximal exercise tests is however not currently recommended by any other impairment guideline.

IMAGING

IMAGING

Imaging studies are primarily useful for confirming the diagnosis of lung disease. They are less useful in rating respiratory impairment, since the correlation between radiographic abnormality and physiologic dysfunction is imperfect.

Chest radiographic evidence of pneumoconiosis is rated according to the 2011 International Labor Organization’s (ILO) International Classification of Radiographs of Pneumoconiosis scheme (also called “B-reading”). The 2011 standards extended the applicability of the Classification to digital chest radiographs. The extent or profusion of small-sized parenchymal opacities is rated as 0, 1, 2, or 3. An intermediate score of 1/0 (i.e., profusion of small opacities greater than 0 but less than 1 profusion score) is often used to confirm the presence of pneumoconiosis.

Some determinations of respiratory impairment are not dependent on PFTs. They are based on environment-related diagnoses (e.g., occupational asthma or hypersensitivity pneumonitis) and warrant proscription of continuing exposure to inciting agents). In addition, impairment may be based upon prognosis (e.g., unresectable lung cancer) or public health considerations (e.g., pulmonary tuberculosis).

SCIENTIFIC RATIONALE FOR CHOICE OF TESTS USED FOR IMPAIRMENT EVALUATION FOR CHRONIC RESPIRATORY DISORDERS

Impairment evaluation for chronic respiratory conditions is based upon PFT values at rest and with exercise. The premise for these tests is that ![]() O2peak reasonably measures ability to work, and that resting PFTs, such as forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and DLCO, reasonably predict

O2peak reasonably measures ability to work, and that resting PFTs, such as forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and DLCO, reasonably predict ![]() O2peak values.

O2peak values.

OXYGEN CONSUMPTION AT PEAK EXERCISE AS THE GOLD STANDARD FOR MEASURING ABILITY TO WORK

OXYGEN CONSUMPTION AT PEAK EXERCISE AS THE GOLD STANDARD FOR MEASURING ABILITY TO WORK

Most of the available medical literature appears to support the view that ![]() O2peak value, expressed as mL/kg/min, is the gold standard for assessing impairment.18,19 With exercise on a cycle ergometer,

O2peak value, expressed as mL/kg/min, is the gold standard for assessing impairment.18,19 With exercise on a cycle ergometer, ![]() O2 increases linearly with external work,17 and

O2 increases linearly with external work,17 and ![]() O2peak represents the maximal work an individual can perform during a short burst of activity. Some have advocated use of percent predicted

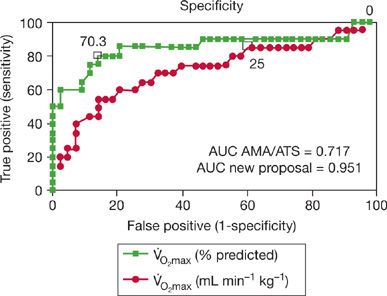

O2peak represents the maximal work an individual can perform during a short burst of activity. Some have advocated use of percent predicted ![]() O2peak values (i.e., loss of aerobic capacity), instead of

O2peak values (i.e., loss of aerobic capacity), instead of ![]() O2peak expressed in mL/kg/min (i.e., remaining aerobic ability) for evaluating impairment in patients with respiratory disease, since the latter approach overestimates impairment in older and obese subjects Fig. 38-1.20,21 In addition, some consider the value for

O2peak expressed in mL/kg/min (i.e., remaining aerobic ability) for evaluating impairment in patients with respiratory disease, since the latter approach overestimates impairment in older and obese subjects Fig. 38-1.20,21 In addition, some consider the value for ![]() O2 at anaerobic threshold (

O2 at anaerobic threshold (![]() O2AT) as a better index for work ability than

O2AT) as a better index for work ability than ![]() O2peak.21 Individuals are unable to sustain work rates above anaerobic threshold values. However, no major guidelines currently use percent predicted

O2peak.21 Individuals are unable to sustain work rates above anaerobic threshold values. However, no major guidelines currently use percent predicted ![]() O2peak values or

O2peak values or ![]() O2AT to rate impairment.

O2AT to rate impairment.

Figure 38-1 Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves of two classifications (AMA/ATS vs. new classification proposed by Neder et al.), using the ![]() O2 at anaerobic threshold (

O2 at anaerobic threshold (![]() O2AT) as the “gold standard.” The open squares represent the cutoffs for normality for

O2AT) as the “gold standard.” The open squares represent the cutoffs for normality for ![]() O2peak using the two classification schema. Neder et al. have advocated the use of percent predicted

O2peak using the two classification schema. Neder et al. have advocated the use of percent predicted ![]() O2peak values (i.e., loss of aerobic capacity) instead of

O2peak values (i.e., loss of aerobic capacity) instead of ![]() O2peak in mL/kg/min (i.e., remaining aerobic ability) for the evaluation of impairment in patients with respiratory disease since the latter approach overestimates impairment in older and obese subjects. AMA, American Medical Association; ATS, American Thoracic Society; AUC, area under the ROC curve;

O2peak in mL/kg/min (i.e., remaining aerobic ability) for the evaluation of impairment in patients with respiratory disease since the latter approach overestimates impairment in older and obese subjects. AMA, American Medical Association; ATS, American Thoracic Society; AUC, area under the ROC curve; ![]() O2, oxygen consumption. (Reproduced with permission from Neder JA, Nery LE, Bagatin E, Lucas SR, Ancao MS, Sue DY. Differences between remaining ability and loss of capacity in maximum aerobic impairment. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1998;31(5):639–646.)

O2, oxygen consumption. (Reproduced with permission from Neder JA, Nery LE, Bagatin E, Lucas SR, Ancao MS, Sue DY. Differences between remaining ability and loss of capacity in maximum aerobic impairment. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1998;31(5):639–646.)

COMPARISON OF RESTING PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTS WITH OXYGEN CONSUMPTION AT PEAK EXERCISE

COMPARISON OF RESTING PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTS WITH OXYGEN CONSUMPTION AT PEAK EXERCISE

Low values for resting PFTs (i.e., FEV1 or DLCO) predict low ![]() O2peak levels; poor scores on the Short Physical Performance Battery (tests that assess lower extremity function); less distance walked during the 6-minute walk test; and a greater risk of self-reported functional limitation.22,23

O2peak levels; poor scores on the Short Physical Performance Battery (tests that assess lower extremity function); less distance walked during the 6-minute walk test; and a greater risk of self-reported functional limitation.22,23

FEV1 is linearly correlated with ![]() O2peak levels,23 but the reported correlations vary widely between studies, resulting in variance values ranging from 0.25 to 0.71.23–28 Use of absolute versus percent predicted values largely yield similar correlation measures.27 Although some studies demonstrate that FEV1 and forced vital capacity (FVC) have similar predictive value for

O2peak levels,23 but the reported correlations vary widely between studies, resulting in variance values ranging from 0.25 to 0.71.23–28 Use of absolute versus percent predicted values largely yield similar correlation measures.27 Although some studies demonstrate that FEV1 and forced vital capacity (FVC) have similar predictive value for ![]() O2peak levels,27 most report FEV1 to be a stronger predictor than FVC. A 2005 ATS statement indicated that percent predicted FEV1, rather than FVC, should be used to categorize severity of impairment for all respiratory diseases.8 The predictive ability of FEV1 for

O2peak levels,27 most report FEV1 to be a stronger predictor than FVC. A 2005 ATS statement indicated that percent predicted FEV1, rather than FVC, should be used to categorize severity of impairment for all respiratory diseases.8 The predictive ability of FEV1 for ![]() O2peak increases if it is used in combination with another variable, such as DLCO, minute ventilation (

O2peak increases if it is used in combination with another variable, such as DLCO, minute ventilation (![]() E), or dead space ventilation measure during exercise (VD/VT).27 DLCO does not predict

E), or dead space ventilation measure during exercise (VD/VT).27 DLCO does not predict ![]() O2peak among healthy controls,24 but it does so among subjects with COPD and those with occupational lung diseases, where it may account for a variance of 0.25 to 0.76 in various studies.26,27,29

O2peak among healthy controls,24 but it does so among subjects with COPD and those with occupational lung diseases, where it may account for a variance of 0.25 to 0.76 in various studies.26,27,29

Despite the previously noted correlations in population studies, resting PFTs cannot accurately predict ![]() O2peak values among individuals, particularly those with occupational lung diseases. In a comparison study of impairment ratings obtained using simultaneous resting PFTs and cardiopulmonary exercise tests conducted in 216 ambulatory patients with COPD, the two methods resulted in similar impairment rating in only 30.1%. Ratings were similar between the two methods in the extreme subgroups of normal or severely impaired individuals. 61.1% were found to be less impaired according to exercise testing than according to resting PFTs, and 8.8% were more impaired according to exercise testing than resting PFTs (Table 38-4). These data suggest that use of resting PFTs and exercise testing for rating impairment often yields discrepant results.

O2peak values among individuals, particularly those with occupational lung diseases. In a comparison study of impairment ratings obtained using simultaneous resting PFTs and cardiopulmonary exercise tests conducted in 216 ambulatory patients with COPD, the two methods resulted in similar impairment rating in only 30.1%. Ratings were similar between the two methods in the extreme subgroups of normal or severely impaired individuals. 61.1% were found to be less impaired according to exercise testing than according to resting PFTs, and 8.8% were more impaired according to exercise testing than resting PFTs (Table 38-4). These data suggest that use of resting PFTs and exercise testing for rating impairment often yields discrepant results.