CLINICAL PRESENTATION

With the growing emphasis on “minimally invasive” treatment of cardiovascular diseases, there has been a marked increase in the use of percutaneous diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. The most frequently used arterial access site is the common femoral artery, and the reported prevalence of femoral pseudoaneurysms is in the range of 0.05% to 4%.3–5 Some devices for catheter-based interventions require large sheath sizes as well as aggressive use of anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents; these factors appear to increase the risk for pseudoaneurysms. The method used to achieve hemostasis after sheath removal may also contribute to this risk. These developments have increased the incidence of other complications related to percutaneous femoral artery puncture, including groin hematomas, retroperitoneal bleeding, and arteriovenous fistulas.

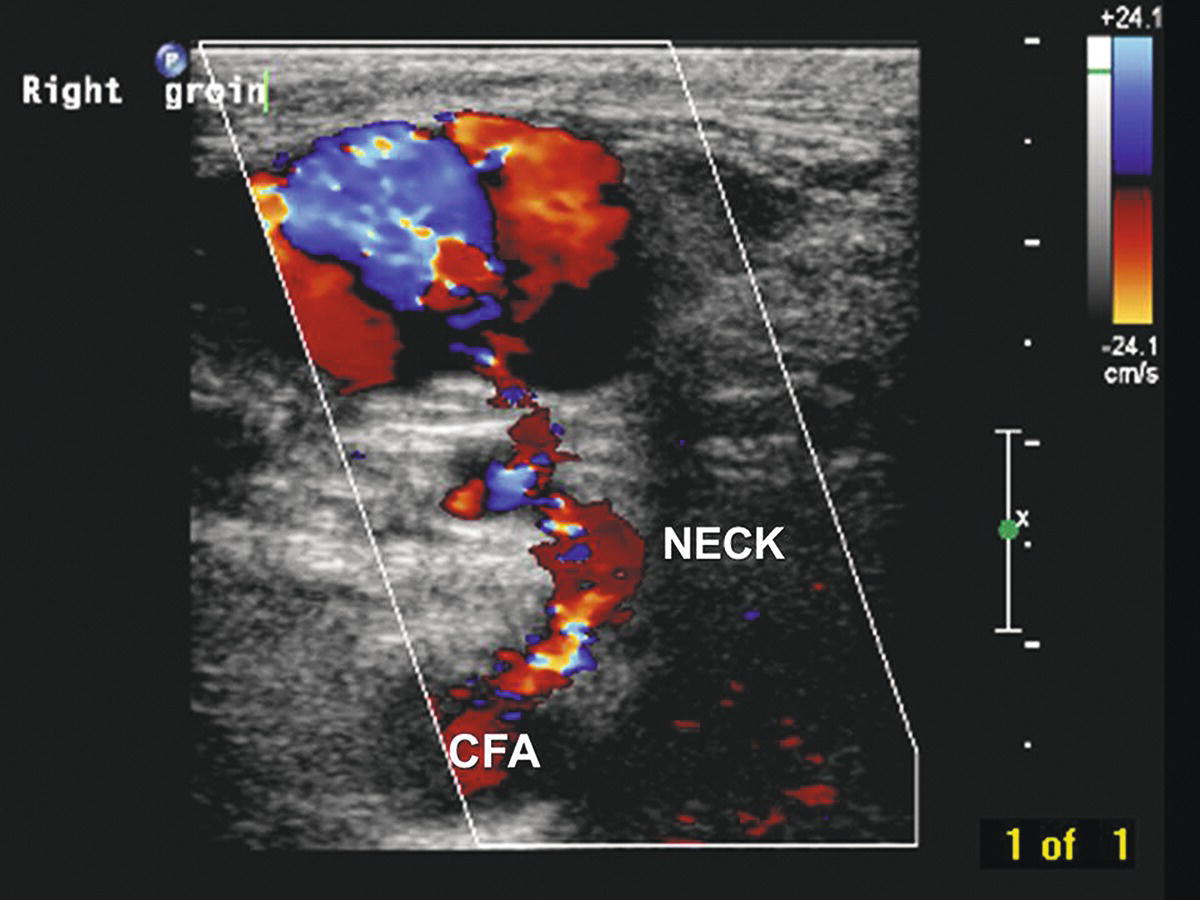

Femoral pseudoaneurysms usually originate at the arterial puncture site from the wall of the artery closest to the skin surface. This is most often at the level of the common femoral artery but may involve any segment from the distal external iliac to the proximal superficial femoral or deep femoral artery. A pseudoaneurysm forms when the puncture site fails to seal and a cavity filled with arterial blood forms adjacent to the arterial wall. This cavity is connected to the arterial lumen by a “neck” of variable length and often contains both flowing blood and laminated thrombus (Fig. 32.1). Pseudoaneurysm cavities are typically in the range of 1 to 3 cm in diameter when first detected, and some consist of multiple interconnected lobes. Rarely, a femoral pseudoaneurysm is associated with an arteriovenous fistula originating from a separate puncture site. Although the natural history of femoral pseudoaneurysms is unpredictable, those with flow-filled cavities less than 2 cm in maximum diameter are more likely to thrombose spontaneously than are those with larger cavities.

FIGURE 32.1. Transverse B-mode and color-flow image of a right femoral pseudoaneurysm shows the native common femoral artery (CFA) and pseudoaneurysm neck (NECK) connecting to the active pseudoaneurysm cavity (upper left). The cavity appears partially thrombosed with incomplete color filling.

A femoral pseudoaneurysm should be suspected whenever an enlarging hematoma is noted adjacent to a puncture site within hours to days after a percutaneous arterial procedure. Many patients report a “popping” sensation and pain in the catheterized groin. These signs and symptoms are typically accompanied by extensive ecchymosis of the overlying skin; however, bruising is common in this setting, even in the absence of a pseudoaneurysm. A palpable thrill or continuous bruit over the groin suggests the presence of an arteriovenous fistula, with or without an associated pseudoaneurysm. Palpation usually reveals a tender pulsatile mass, but it is often difficult to distinguish between true pulsatility and transmitted pulsation through a hematoma. Therefore, the diagnosis should always be confirmed by duplex ultrasound evaluation.

DIAGNOSIS

Scanning Technique

With the patient supine and the ipsilateral leg externally rotated, initially evaluate the distal external iliac, common femoral, deep femoral, and proximal superficial femoral arteries and veins in a standard fashion for stenosis, aneurysm, or thrombosis. This is typically done with a 5- to 7-MHz linear array transducer. However, B-mode resolution is often poor owing to extravasated blood in the tissue, and a lower-frequency transducer may be needed for adequate depth penetration. A curved array is useful if a large field of view is required, whereas a phased array is best if there is a small acoustic window or deep inguinal crease. After the native vessels have been assessed, scan the surrounding area for masses. Color-flow imaging is helpful for distinguishing between pseudoaneurysms and nonvascularized masses such as hematomas, seromas, or enlarged lymph nodes. Although pseudoaneurysms are the most frequently suspected postcatheterization vascular problem, other abnormalities that may be present include intimal flaps, arterial thrombosis, arterial dissections, arteriovenous fistulas, extrinsic compression of veins, and deep vein thrombosis.

Ultrasound Findings

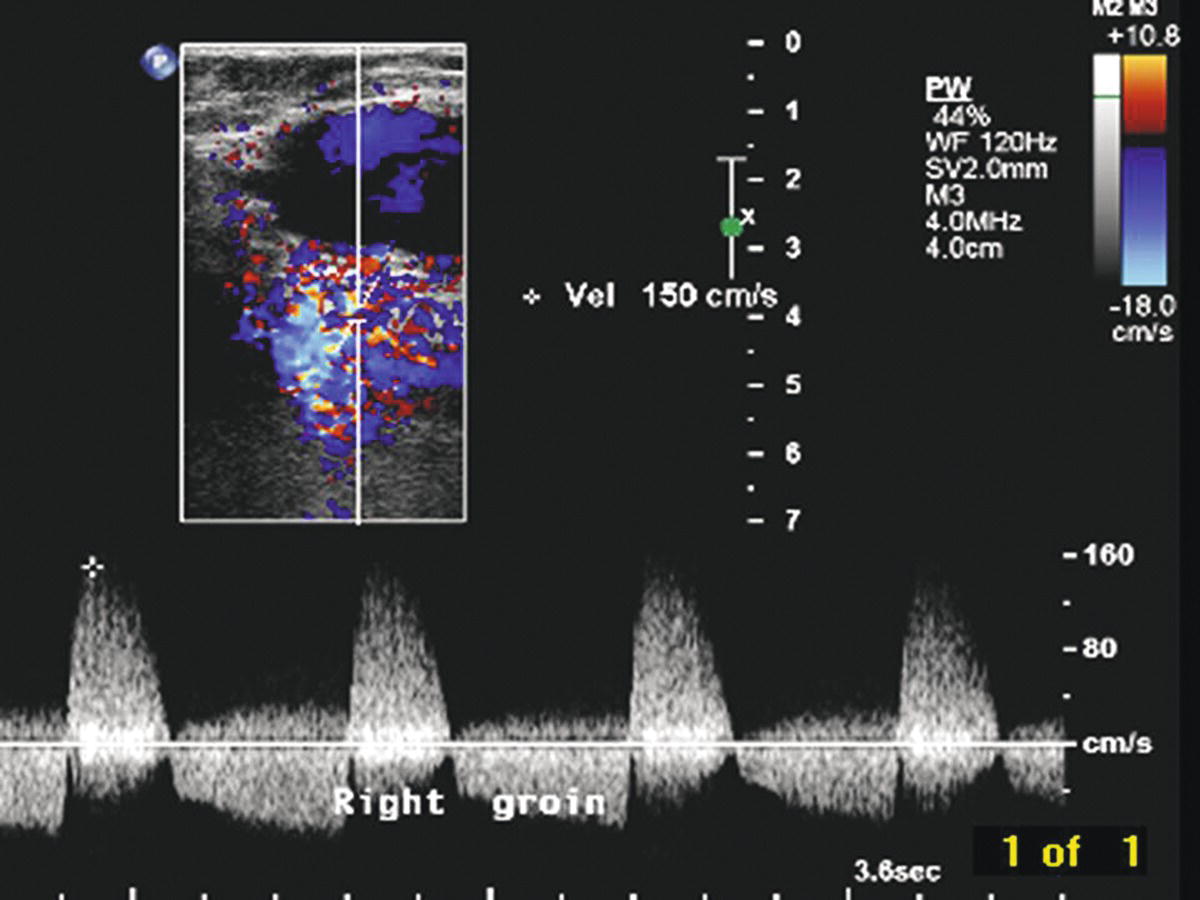

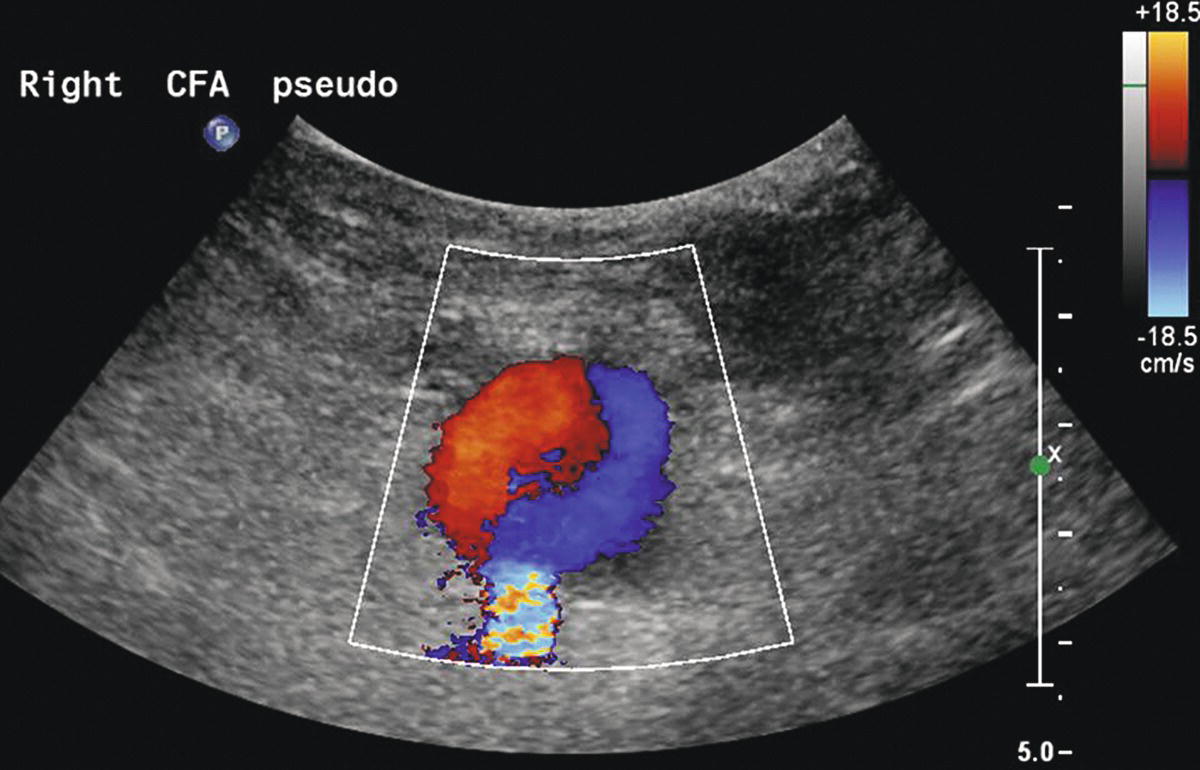

The key features of a pseudoaneurysm on duplex ultrasound are a vascularized cavity connected to the adjacent artery by a neck that exhibits a characteristic “to-and-fro” spectral waveform pattern, representing arterial flow in and out of the pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 32.2). Radial pulsations are usually visible in or around the cavity on B-mode imaging, and arterial flow is detectable within the cavity by both pulsed and color-flow Doppler. A distinctive “yin-yang” pattern is often seen on the color-flow image (Fig. 32.3). Document the size and location of the pseudoaneurysm, and follow the neck to locate the exact point of origin. Also measure the length of the neck between the arterial defect and the vascularized cavity. Whereas the true size of a pseudoaneurysm includes both the active or vascularized portion and any surrounding thrombus, the most important feature is the size of the vascularized cavity. Images and reports should clearly distinguish between these measurements.

FIGURE 32.2. Pulsed Doppler spectral waveform shows the typical “to-and-fro” flow pattern found in a pseudoaneurysm neck. Note both forward (positive) and reverse (negative) velocity components.

FIGURE 32.3. Ultrasound image of a femoral pseudoaneurysm shows the “yin-yang” color-flow pattern in the vascularized or active portion of the cavity.

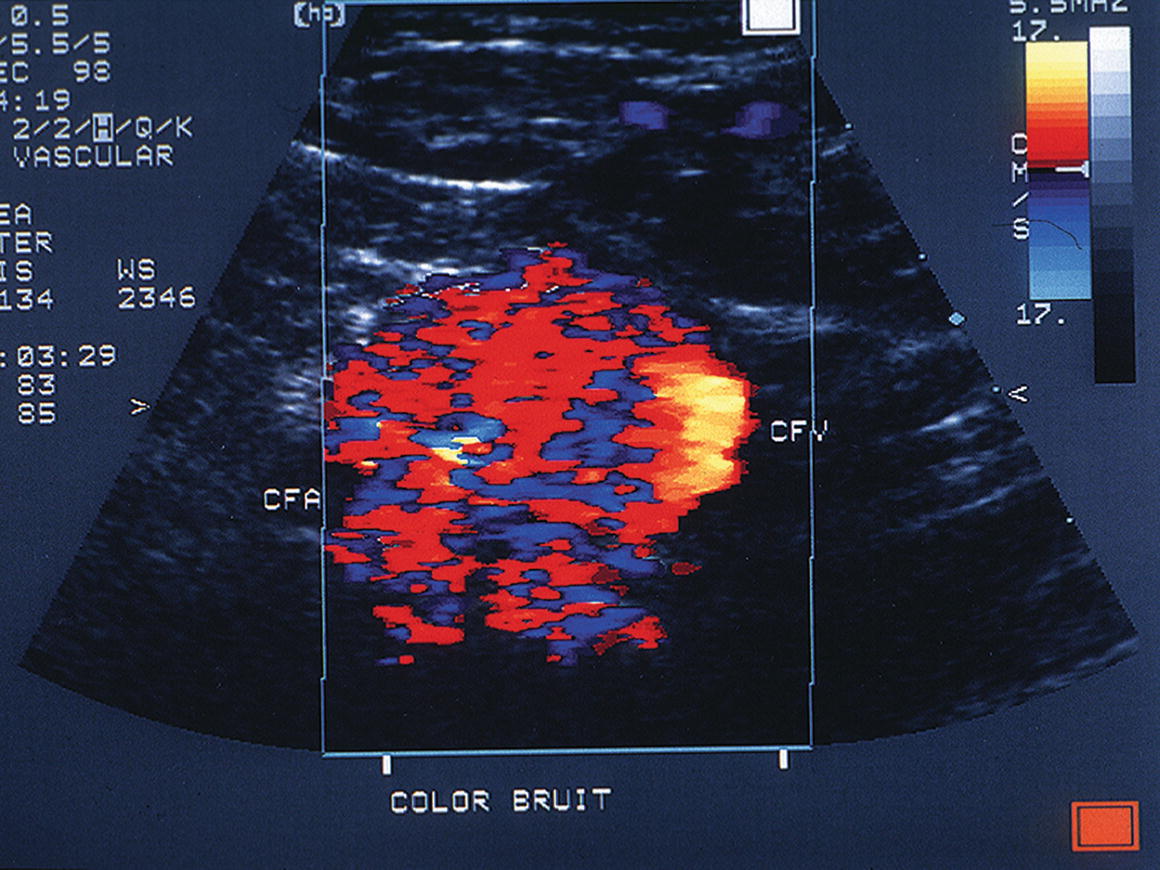

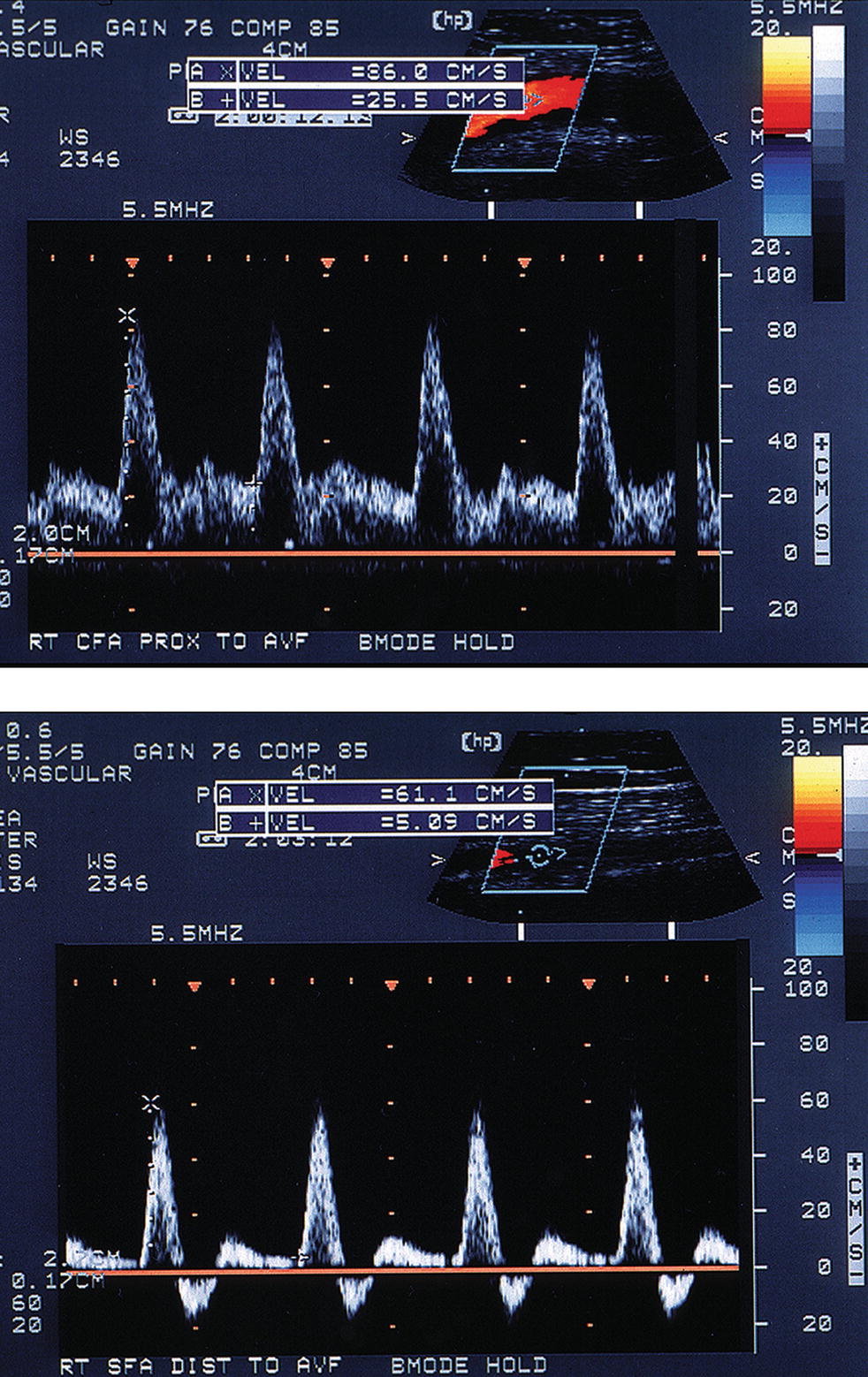

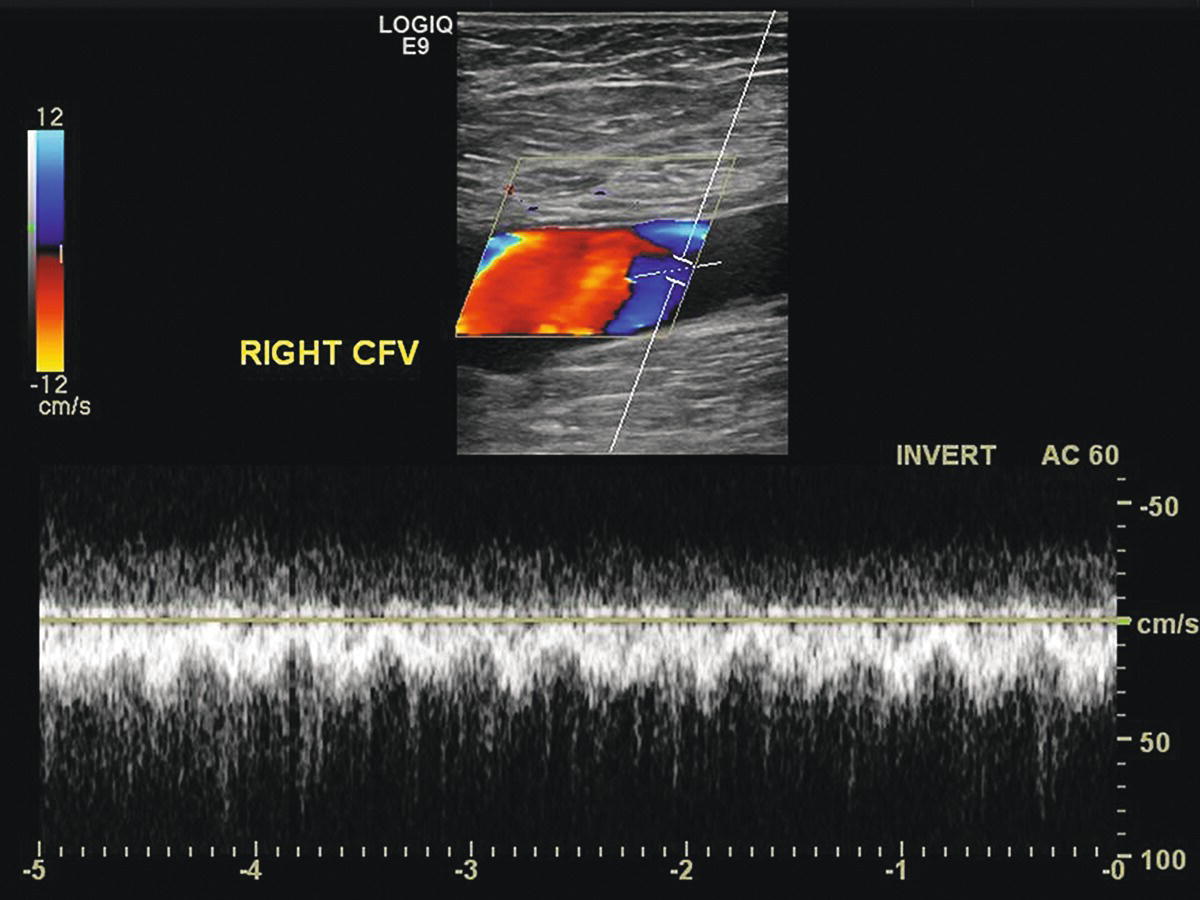

Arteriovenous fistulas occur when both the artery and the adjacent vein have been punctured, resulting in a persistent high-flow connection between the two vessels. These lesions usually produce a striking image on color-flow Doppler in the area of the communicating channel, with a prominent “color bruit” (Fig. 32.4). Elevated peak velocities and aliasing are typically found at the site of the fistula, with a characteristic high-velocity/low-pulsatility waveform (Fig. 32.5). Arteriovenous fistulas can also be located by identifying increased systolic and diastolic velocities in the artery proximal to the lesion that normalize distally (Fig. 32.6). Venous segments proximal (central) to the fistula contain turbulent and pulsatile flow patterns (Fig. 32.7).

FIGURE 32.4. Prominent color-flow bruit associated with an arteriovenous fistula between the common femoral artery (CFA) and the common femoral vein (CFV).

(From Smith WB, Zaccardi M, Zierler RE. Diagnosis and treatment of femoral pseudoaneurysms. Vasc Ultrasound Today 2005;10:199–220. Used with permission.)

FIGURE 32.5. A high-velocity/low-pulsatility spectral wave- form from a postcatheterization arteriovenous fistula between the right profunda femoris artery (PFA) and the common femoral vein (CFV). Note the very high diastolic flow velocity.

FIGURE 32.6. Changes in the arterial flow pattern proximal and distal to an arteriovenous fistula. Top,Common femoral artery spectral waveform taken proximal to the fistula shows increased systolic and diastolic velocities (low resistance pattern). Bottom,Superficial femoral artery spectral waveform taken distal to the same fistula shows decreased velocities and the return of a high-resistance triphasic flow pattern. (From Smith WB, Zaccardi M, Zierler RE. Diagnosis and treatment of femoral pseudoaneurysms. Vasc Ultrasound Today 2005;10:199–220. Used with permission.)

FIGURE 32.7. Turbulent and pulsatile spectral waveform from the common femoral vein (CFV) proximal (central) to the arteriovenous fistula shown in Figure 32.5.

APPROACHES TO TREATMENT

Based on the risk of progressive enlargement and rupture, most pseudoaneurysms should be treated at the time of diagnosis. However, small asymptomatic pseudoaneurysms with vascularized cavities less than 2 cm in diameter may be followed by serial ultrasound evaluations and treated if they do not thrombose spontaneously. Patients on antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants are less likely to show spontaneous thrombosis. Options for treatment include direct open surgical repair, ultrasound-guided compression, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection. Open surgery requires exposure of the puncture site through a groin incision and direct repair of the arterial defect by simple suture or patch angioplasty. Any concomitant arterial defects such as intimal flaps or fistulas can also be repaired using this approach. Although direct surgical repair is highly effective and relatively safe, many patients with femoral pseudoaneurysm have significant medical comorbidities that make a less invasive approach preferable.

Permanent obliteration of a femoral pseudoaneurysm cavity by ultrasound-guided compression was first described in 1991.6 This technique involves direct compression of the pseudoaneurysm cavity using the ultrasound probe, with the goal being to occlude the neck of the pseudoaneurysm without completely occluding the adjacent artery. Although success rates of up to 75% have been reported with ultrasound-guided compression, this approach has significant limitations.7,8 Compression of a groin pseudoaneurysm is physically difficult for the operator and painful for the patient. In addition, prolonged periods of compression—up to 1 hour or more—are often required. For these reasons, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection is now clearly the preferred initial treatment for most femoral pseudoaneurysms.

Thrombin is an enzyme that converts fibrinogen to fibrin, a critical step in the process of blood coagulation. Although products containing human thrombin are now available for clinical use (Recothrom, ZymoGenetics, Inc.), most of the reported experience with ultrasound-guided thrombin injection for treatment of femoral pseudoaneurysms has been with thrombin preparations of bovine origin (Thrombin-JMI, King Pharmaceuticals, Inc.). These products are labeled “topical” thrombin, with the intended use being as a hemostatic agent on the surfaces of bleeding tissues. The instructions for use in the standard topical thrombin kit state that it should not be injected, so treatment of femoral pseudoaneurysms is considered to be an “off-label” use. Nevertheless, this approach is commonly practiced and is clearly safe and effective. In 2002, the American Medical Association created a specific CPT (current procedural terminology) code (36002) to cover “injection procedures (e.g., thrombin) for percutaneous treatment of extremity pseudoaneurysm.”

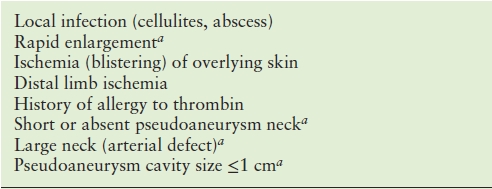

Although most patients with postcatheterization femoral pseudoaneurysms are good candidates for ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, some contraindications must be recognized (Table 32.2). These include any evidence of infection in the groin, ischemia (blistering) of the overlying skin, distal limb ischemia, and any history of allergic reaction to thrombin or bovine materials (when bovine thrombin is used). Rapid enlargement can be a sign of serious bleeding requiring immediate surgical repair. When ultrasound evaluation shows a short or absent pseudoaneurysm neck, or a very large arterial defect, the risk of propagation of thrombus into the native artery is higher, and surgical repair may be preferable. Small pseudoaneurysms, particularly those with active cavities less than 1 cm in diameter, can be difficult to inject and may thrombose spontaneously.

TABLE 32.2 Contraindications to Ultrasound-guided Thrombin Injection

aRelative contraindications (see text).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree