INTRODUCTION TO LABORATORY ANALYSIS OF SPUTUM

Learning Objectives

The student will be able to describe the best method for sputum collection and the diagnostic information to be gained from its analysis.

The student will be able to recognize the special stains used on sputum and pleural fluids to aid in making a diagnosis.

The student will be able to list the characteristics of a normal pleural fluid and mechanisms for the formation of a pleural effusion.

The student will be able to distinguish between an exudate and a transudate and list laboratory testing used to make such a determination.

The student will be able to identify the major cell types found in pleural effusions and explain how these correlate with various disease processes.

Pneumonia is an infectious process affecting the parenchyma of the lungs. Infectious agents that are potentially responsible for such pneumonia include bacteria, fungi, viruses, and rarely parasites. The goal when evaluating sputum in the laboratory is to confirm the diagnosis of pneumonia, identify the etiologic agent(s) responsible for producing the present disease, and guide selection of appropriate antibiotic therapy.

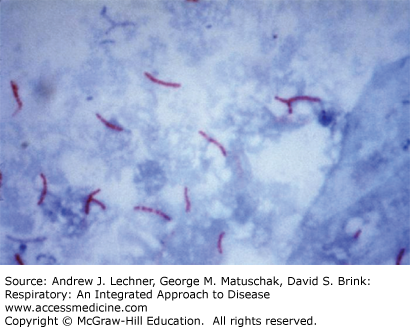

Expectorated sputum is the most common lower respiratory tract specimen received in the clinical microbiology laboratory. Sputum can be collected either by spontaneous expectoration or after sputum induction, which is collected following instillation or inhalation of an irritating aerosol such as hypertonic saline. Sputum induction is performed when the patient cannot produce sputum. Generally, the first morning sputum samples are the best specimens; a volume of 5-10 mL is usually adequate. Because many received specimens consist mostly of pharyngeal secretions and upper airway cells rather than sputum, the first step in evaluating a specimen’s suitability uses a Gram stain (Fig. 19.1). Use of such a Gram stain assesses specimen acceptability for further processing, and aids interpretation by identifying the morphology of any likely etiologic agents of pneumonia in a specimen that is acceptably purulent.

Ideally, a sputum sample examined microscopically should contain <10 epithelial cells per low power field (LPF), or from 10-25 epithelial cells and >25 leukocytes/LPF. Sputum specimens containing >25 squamous epithelial cells are rejected because these represent oropharyngeal secretions that will be heavily contaminated with normal throat flora. Likewise, a sputum specimen containing no epithelial cells, leukocytes, or bacteria is rejected because the specimen is an inadequate representation of conditions in the intermediate airways. Most hospital laboratories have well-established guidelines of this type, including stipulations as to the handling of such potentially dangerous biological specimens. These guidelines can be adjusted when a particular patient’s needs are communicated to the laboratory personnel.

The Gram stain report on a sputum sample includes the types of organism seen, whether they are gram-positive or -negative, and the architecture of the organism, whether cocci or bacilli. Such information gives important clues as to possible identifications of organisms found. For example, gram-positive cocci that appear as grape-like clusters raise suspicion for Staphylococcus spp., while gram-positive lancet-shaped diplococci suggest Streptococcus pneumoniae. The presence of gram-negative coccobacilli often indicates Haemophilus influenzae. In the same sputum report, the number of organisms present is usually estimated as many, moderate, few, or rare. In most laboratories, these terms pertain to the number of similar organisms present per high power field (HPF) using oil immersion: many >10 organisms/HPF; moderate = 5-10 organisms/HPF, few = 1-5 organisms/HPF, and rare <1 organism/HPF.

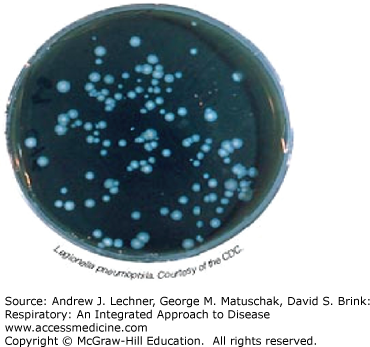

A sputum sample can be cultured as indicated, both for routine bacterial pathogens, as well as for a variety of other microorganisms including Mycobacteriae and fungi (Fig. 19.2). Some culture results are available within days while others, particularly for fungi and Mycobacteriae, may require several weeks to yield definitive results. Sputum smears and cultures for fungi and/or Mycobacteriae must be ordered separately in most laboratory settings, since special culture media are needed for many of the atypical bacterial infections, such as Mycobacterium and Legionella (Fig. 19.3).

Some organisms are best discovered using serology, notably Chlamydia and Mycoplasma. These organisms will not grow on routine microbiological culture media. Urine antigens also can be assessed for Legionella and S. pneumoniae.

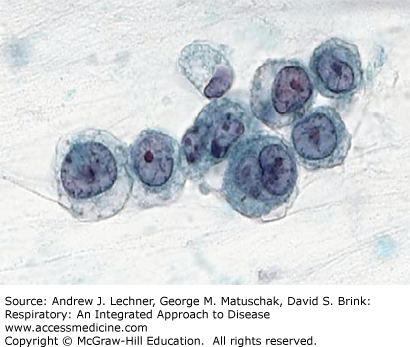

Sputum specimens may also be submitted for cytological exam of individual cells, usually when looking for neoplasms (Chap. 31). For such purposes, the sputum specimen is collected into a cup with a special mucolytic fluid that improves visualization of the cells contained therein (Fig. 19.4). These specimens are sent to surgical pathology and not to the microbiology section of a hospital laboratory. As with other sputum specimens, these should be delivered to the laboratory as soon as possible.

INTRODUCTION TO ANALYSIS OF PLEURAL EFFUSIONS

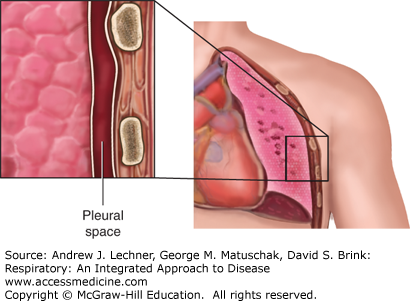

The pleural space often is described as a potential space that exists between the juxtaposed visceral pleura covering the outer surface of the lung and parietal pleura lining the inner surface of the chest wall. As such, the pleural space normally contains just a few milliliters of fluid (Fig. 19.5). Laboratory characteristics of normal pleural fluid include: pH = 7.6, [protein] = 1-2 g/dL (vs plasma [protein] ≅ 7 g/dL), [glucose] ≅ plasma [glucose], and [lactate dehydrogenase] <50% of plasma [LDH]. The number of WBC in pleural fluid is normally <1,000/mL and consists predominantly of mononuclear cells with a few erythrocytes and mesothelial cells. Normally there are <10 mL of pleural fluid in the entire thoracic space of a healthy adult.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree