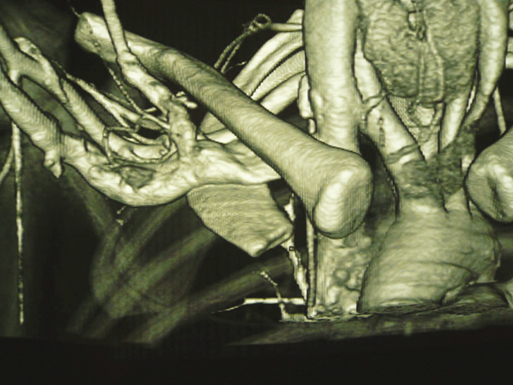

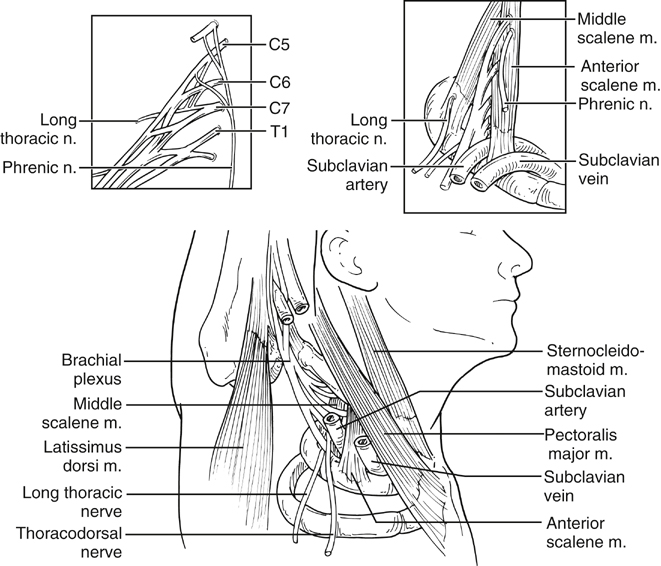

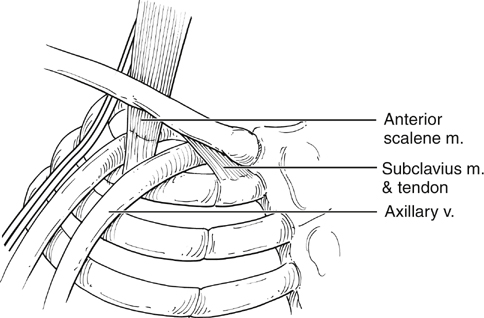

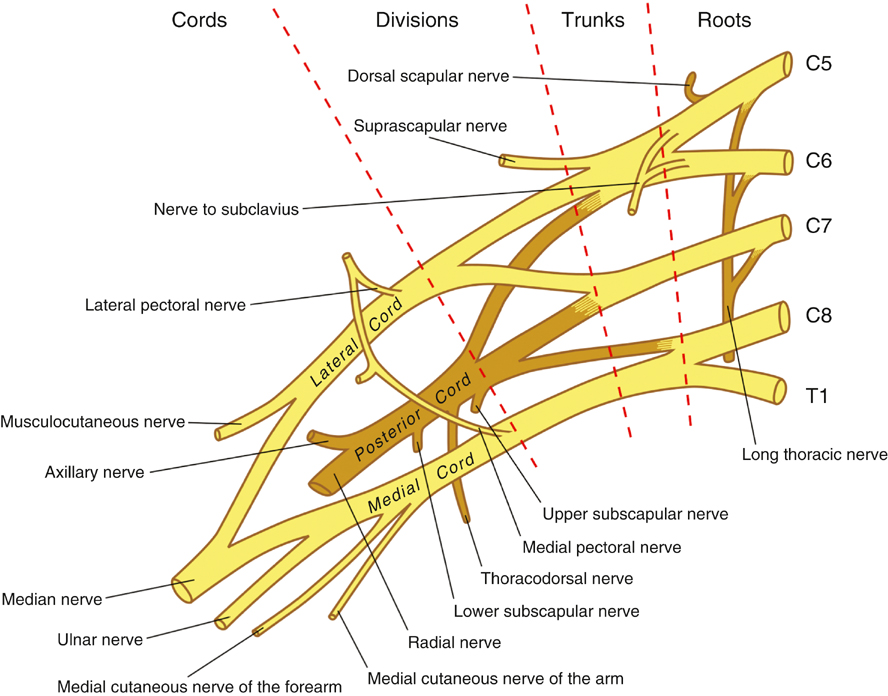

The different forms of TOS can be categorized and best conceptualized by understanding the anatomy. The brachial plexus and subclavian artery run through the triangle formed by the anterior scalene muscle, middle scalene muscle, and first rib (Figure 1). Neurogenic TOS can be thought of as a compartment syndrome affecting the nerves. There is an imbalance between the space allotted for passage of the nerve bundle itself. This can be caused by muscle fibrosis or hypertrophy, brachial plexus inflammation, or abnormal congenital or acquired structures that narrow this area. The artery can also be partially obstructed, almost always by abnormal bone structures, leading to poststenotic dilation and subsequent thrombosis or embolization. By contrast, venous TOS arises from a problem within the anterior part of the thoracic outlet, anterior to the scalene muscle. The vein runs past the junction of the first rib and clavicle, which are connected by the subclavian tendon and costoclavicular ligaments (Figure 2). Although the vein is bounded only by soft tissue posteriorly and superiorly, the nutcracker effect of the first rib and clavicle can produce a chronic injury to the vein. This occasionally manifests as intermittent positional obstruction, but frank venous thrombosis occurs most often. Treatment of these three entities must be individualized. The brachial plexus and subclavian artery run through the triangle bounded by the first rib, anterior scalene muscle, and middle scalene muscle (see Figure 1). This triangle is not a perfect geometric figure. In reality the longest border of the triangle is the anterior scalene muscle, which originates from the C3 to C6 transverse processes and runs anterior to the brachial plexus, inserting upon the scalene tubercle of the first rib. The middle scalene muscle really acts as a pad to the middle and posterior part of the first rib. Very little of the rib itself actually touches the artery or brachial plexus. Not uncommonly, the anterior-most fibers of the middle scalene insert close to the anterior scalene, forming a lenticular orifice for passage of the neural structures. Partly for this reason, some authors have suggested that the first rib does not always have to be removed in neurogenic TOS. The brachial plexus usually is formed by five nerve roots: C5 through C8, and T1. Thus the bottom nerve root lies caudal to the posterior point of resection of the first rib during surgery for TOS. These nerve roots coalesce into three trunks, each in turn giving rise to a posterior and anterior division, the cords and peripheral nerves being formed by combinations of the divisions (Figure 3). The scalene triangle surrounds the plexus at the level of the trunks. The anatomy relevant to venous TOS, by contrast, centers on the anterior portion of the thoracic outlet. The costoclavicular junction is made up by the clavicle and cartilaginous insertion of the first rib into the sternum (see Figure 2). The undersurface of the clavicle is covered with the surprisingly bulky subclavius muscle (Figure 4), which becomes tendinous upon its insertion to the sternum. In addition, there is often a ligament that runs between the clavicle and first rib, the costoclavicular ligament. It is clinically indistinguishable from the subclavius tendon. The clavicle and first rib do not move very much, but when they do, bounded by this anterior fulcrum, they do so with considerable force. It should be noted that there is no firm structure posterior or superior to the vein, and hence no triangle, but the vein is essentially fixed within this nutcracker area of compression and cannot migrate out of the way posteriorly when stressed.

Etiology and Anatomic Pathology of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Anatomy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine