Esophagectomy: Transhiatal and Reconstruction

Robert E. Glasgow

DEFINITION

Transhiatal esophagectomy (THE) or esophagectomy without thoracotomy is defined as removal of the esophagus and upper stomach using an incision in the left anterior neck for purposes of dissection of the upper third of the esophagus via the thoracic inlet, and an upper midline abdominal incision for purposes of dissection of the stomach and lower two-thirds of the esophagus and creation of a conduit for esophageal reconstruction (stomach, colon).

Although THE is usually applied for purposes of treating esophageal and gastroesophageal (GE) junction carcinoma, THE may also be used for treatment of benign esophageal conditions including end-stage achalasia and medically/endoscopically recalcitrant esophageal stricture from caustic injection or end-stage reflux disease and acute perforation.

The remainder of this discussion will focus on the use of THE in the treatment of malignant disease. Most aspects of the diagnostic workup and operative techniques also apply to the evaluation and treatment of benign conditions for which THE is being considered.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

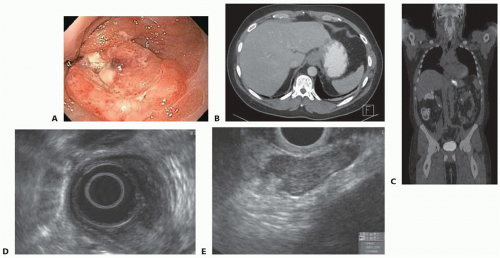

THE is most commonly used in treatment of esophageal cancer. In particular, adenocarcinomas of lower third of the esophagus and Siewert types I and II GE junction adenocarcinoma (FIG 1; Table 1) are optimally suited for this approach.

Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) of the lower third of the esophagus may also be approached via THE, whereas tumors of the middle and upper third of the esophagus usually require transthoracic esophagectomy (TTE) to allow for direct visualization of the dissection of the involved esophagus.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

All patients should undergo a comprehensive medical history with emphasis not only on clinical history pertinent to the primary indication for consideration of THE but also the pertinent comorbid conditions that would influence treatment planning. Included in this history is a comprehensive past surgical history. Prior fundoplication will make dissection of the esophageal hiatus more difficult. Patients with a prior history of gastric resection, for example, may not be candidates for use of the stomach as a conduit for reconstruction because of inadequate length or blood supply. Finally, if the colon is to be considered for use for reconstruction, the influence of prior colectomy on anatomy and blood supply should be very carefully considered.

Whether it be for benign or malignant disease, the principal symptom at the time of presentation for a patient who would undergo THE is dysphagia. Often, these patients have significant nutritional impairment, most notably, weight loss.

In patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and GE junction, a history of GE reflux disease should be elicited as well as a careful history of prior endoscopic and radiographic evaluations. In patients with SCC, a prior and current history of tobacco and alcohol use should be elicited.

A comprehensive physical examination should be performed with special attention to the cervical and supraclavicular areas for enlarged lymph nodes, chest exam for possible effusions, and abdominal exam for palpable masses and periumbilical lymph nodes (Sister Mary Joseph nodule).

Table 1: Siewert Classification for Gastroesophageal Junction Adenocarcinoma | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Upper Endoscopy with Biopsy

All patients presenting with dysphagia should undergo upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and biopsy with the goal of making a diagnosis and localizing the site of obstruction (FIG 1).

Multiple biopsies of suspicious areas (nodules, ulceration, stricture, possible Barrett’s) should be obtained.

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) of focal nodules should be performed to provide accurate T staging and to evaluate degree of differentiation and vascular and/or lymphatic invasion.

For cancer, the location of the tumor as measured from the incisors and GE junction and extent of tumor length, circumferential involvement, and degree of obstruction should be documented.

Computed Tomography of Chest and Abdomen

Once a diagnosis of cancer is made, a computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen with oral and intravenous contrast is done.

Tumor location, locoregional involvement or invasion, regional and extraregional lymph node involvement, and metastatic disease should be evaluated and recorded.

If metastasis is suspected, biopsy of concerning lesions should be undertaken to confirm stage and direct palliative treatment.

Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography

In patients whom a standard CT of the chest and abdomen is unremarkable, a positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) should be performed again to confirm primary tumor location and extent, evaluate regional and extraregional nodal involvement, and exclude occult metastases.

Endoscopic Ultrasound

In patients without metastatic disease (stage 4), an endoscopic ultrasound is done to document depth of invasion of the tumor (T stage) and evaluate mediastinal and perigastric/celiac lymph node involvement (N stage). Biopsy of suspicious lymph nodes is indicated.

All patients should then be assigned a pretreatment TNM stage to guide treatment planning discussions, preferably under the direction of a multidisciplinary treatment planning conference attended by surgical, medical, and radiation oncology.1 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) defines optimal treatment planning algorithms.2

In considering options for reconstruction, the two most common conduits are the stomach and colon. Although variations in stomach blood supply are very rare, variations in colonic blood supply are common enough to justify preoperative evaluation of arterial anatomy and collateral circulation by visceral angiography in planning choice of conduit.

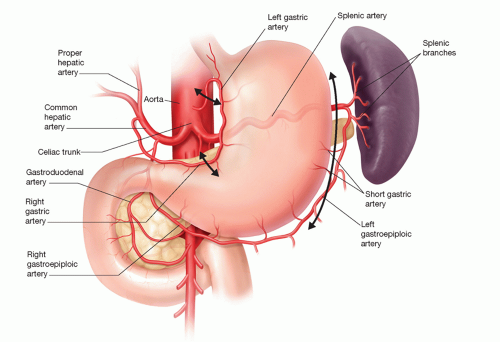

For purposes of using the stomach as a conduit for esophageal reconstruction, an intact right gastric and, more importantly, right gastroepiploic artery is imperative (FIG 2).

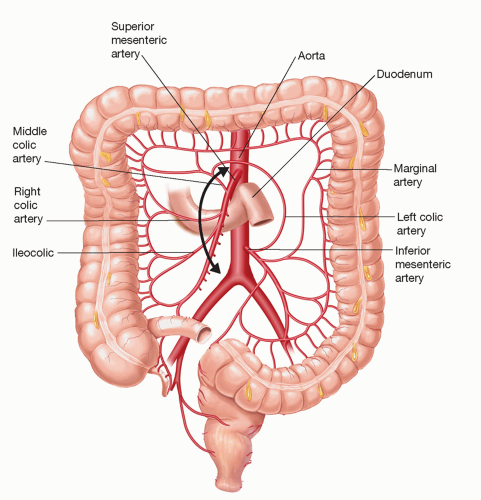

For purposes of the colon as a conduit for esophageal reconstruction following a THE, an adequate collateral blood supply via an intact marginal artery is required (FIG 3). Obviously, a colonoscopy to exclude and/or treat colonic pathology must be done prior to use of the colon.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

As THE is a technically complex operation with a high degree of associated morbidity and mortality, this operation should be done by surgical teams experienced in the perioperative management of these patients.3-5 This includes experienced operating room personnel and anesthesiologists.

Preoperative Planning

Patients should undergo preoperative evaluation by the surgical and anesthesia team for purposes of mitigating perioperative risks in the area of cardiac, pulmonary, and renal comorbidities.

A discussion should be done with the patient as to how pain will be measured and managed following surgery. Regional anesthetics such as an epidural catheter are very

helpful in alleviating pain, thereby allowing the patient to be more engaged in early mobilization and physical therapy.

Perioperative antibiotics should be administered within 60 minutes of skin incision and redosed in a timely manner during the operation. Cefazolin, dosed to weight specifications and redosed every 4 hours, is recommended. Cefoxitin can also be used and redosed every 3 hours. For patients with a beta-lactam allergy, clindamycin or vancomycin and aminoglycoside or aztreonam or fluoroquinolone are used. All prophylactic antibiotics are not necessary beyond surgery completion.6

Perioperative monitoring with an arterial line is helpful especially during blunt mediastinal esophagus dissection where transient hypotension is common because of decreased venous return and compression on the heart. Rarely is a central line indicated.

Appropriate deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis is required. Intermittent sequential compression devices should be placed prior to induction of anesthesia and continued after surgery. Chemical prophylaxis should be instituted postoperatively once clinically indicated.

Urinary catheters are placed following induction of anesthesia and discontinued within 24 hours of surgery.

Positioning

Patients undergoing THE are positioned supine on the operating room table (FIG 4).

Both arms are tucked and pressure points padded to prevent injury during the course of the operation.

A towel or medium gel roll is placed behind the shoulders to allow for mild extension of the neck. This is of particular importance in obese, short-necked patients.

The head is rotated 30 degrees to the right to open exposure to the left neck.

Placement of Surgical Incisions

A midline laparotomy from the xiphoid process to the umbilicus is made (FIG 4).

After verifying the patient to be a candidate for resection and verifying that THE can proceed, a 5-cm incision is made overlying the anterior border of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle with the inferior extent at the head of the clavicle. Contraindications to THE include difficult mediastinal blunt dissection of the esophagus because of tumor or treatment effect, excessive mediastinal bleeding with blunt dissection, and inadequate conduit length for reconstruction.

FIG 3 • Colon blood supply for purposes of using the colon as a conduit for reconstruction following THE. |

TRANSHIATAL ESOPHAGECTOMY

Abdominal Exploration to Exclude Metastatic Disease

Upon entering the abdomen, visceral and parietal peritoneal surfaces are palpated to exclude occult peritoneal carcinomatosis. This should include inspection of the lesser sac by opening thru the gastrocolic omentum.

The liver is palpated for suspicious nodules and biopsy performed. Intraoperative ultrasound can be a useful adjunct in this step. If indeterminate lesions are noted on preoperative imaging, ultrasound-guided biopsy is indicated.

Metastatic disease is an absolute contraindication to proceeding with surgical resection.

Exploration of the Esophageal Hiatus to Determine Local Resectability

Prior to proceeding with dissection of the stomach, the esophageal hiatus is explored to make sure the distal esophagus and GE junction can be dissected free of the

esophageal hiatus and surrounding abdominal and mediastinal structures. If so, and in the absence of metastatic disease, resection can proceed.

This dissection and subsequent dissections are facilitated by use of an electrosurgical device such as an ultrasonic or bipolar scalpel.

The pars flaccida is opened, including division of an accessory or replaced left hepatic artery, if necessary.

The peritoneum and phrenoesophageal membrane overlying the junction of the right crus of the diaphragm and esophagus is incised allowing the esophagus to be dissected off the right crus.

The phrenoesophageal membrane just cephalad to the GE fat pad is divided as is the peritoneal reflection overlying the angle of His.

The esophagus is dissected off the left crus of the diaphragm and esophagus encircled with a 1-in Penrose drain (FIG 5).

The esophagus and GE junction are then dissected free of the crural confluence of the esophageal hiatus, and esophagus with associated periesophageal fatty tissue and lymph nodes dissected free of the esophageal hiatus and underlying aorta.

If the esophagus and GE junction are free of surrounding structures, resection can proceed. If adherent to or invading the pleura, pericardium, or diaphragm (T4a), resection of these structures can be performed. If adherent to the aorta, vertebral body, or trachea (T4b), resection should be aborted.

Mobilization of the Stomach and Duodenum

Once it is determined that resection can proceed, the stomach and duodenum are mobilized. Most often, the stomach is used as the conduit for reconstruction following THE. Therefore, mobilization of the stomach for purposes of proceeding with the esophagectomy and for purposes of the creation of the gastric conduit occur simultaneously.

The right gastroepiploic artery and vein are identified along the greater curvature of the stomach. An adequate pulse in this vessel is imperative if the stomach is to be used for the reconstruction (FIG 6). These vessels terminate at the bare area roughly one-half the distance along the greater curvature between the pylorus and GE junction. It is imperative to preserve these vessels as they are the blood supply to and from the conduit.

Once these vessels are identified, the gastrocolic ligament is entered several centimeters from the bare area entering the lesser sac.

Using an electrosurgery device, the gastrosplenic ligament and short gastric vessels are divided proceeding along the greater curvature toward the esophageal hiatus. Placing a surgical clip on the distal ends of larger vessels, including the left gastroepiploic artery, can ensure ongoing hemostasis of these vessels. The posterior leaflet of the gastrosplenic ligament is likewise divided as are the congenital adhesions of the stomach to the anterior surface of the pancreas. This frees the greater curvature.

Division of the gastrocolic ligament then proceeds distally, paying careful attention to stay at least a few centimeters away from the right gastroepiploic vessels (FIG 7). Careful attention should be paid to not placing traction or trauma to these vessels while freeing the stomach from the colon. This is especially true as one frees the stomach from the anterior surface of the pancreas and approaches the origin of these vessels from under the duodenal bulb. Traction of the vein, in particular, can traumatize these vessels resulting in impaired venous outflow and conduit venous congestion.

After freeing the stomach from the colon, a Kocher maneuver is performed to permit mobilization of the duodenum. An adequate Kocher maneuver permits mobilization of the pylorus to reach the esophageal hiatus (FIG 8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree