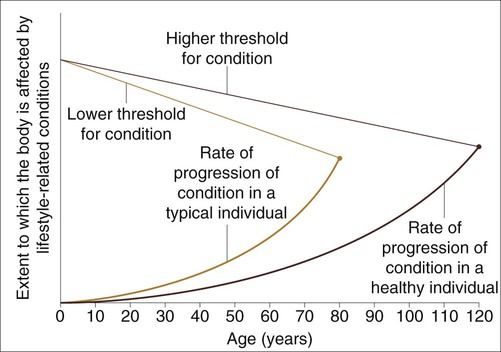

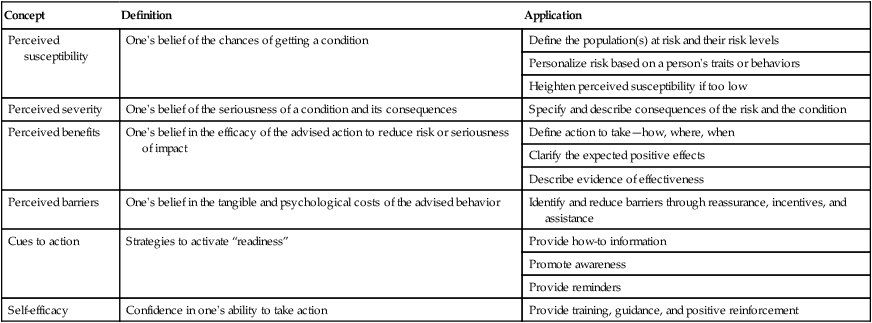

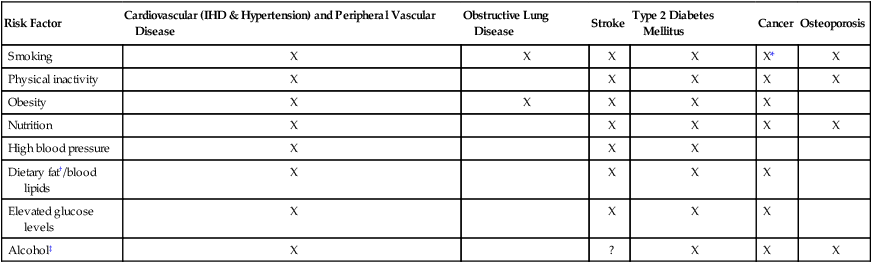

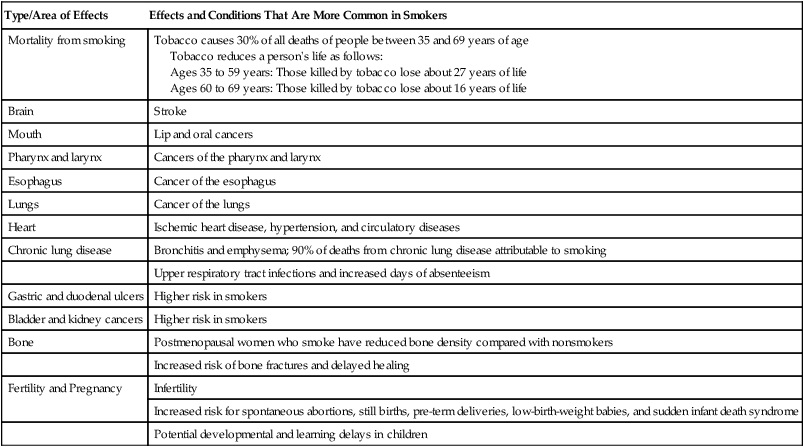

To address the gap between lifestyle practices and the body of knowledge on the relationship between lifestyle choices and health,1 a societal commitment to reducing the number of patients rather than increasing the focus on biomedical care (drugs and surgery) has never been more urgent. Physical therapists are uniquely qualified and strategically positioned as health care professionals to lead in the translation of this well-established body of knowledge into daily practice.2 A consideration of the risks of lifestyle-related conditions in every individual is consistent with a comprehensive model of best practice in the context of epidemiological trends—that is, evidence-based practice in the context of practice priorities that are themselves informed by evidence. This chapter expands these concepts and outlines principles for applying them proactively and as a priority in the health care of every patient. Physical therapists can have a major impact on the leading priorities of health care, one individual at a time. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a complete state of physical, emotional and social well-being”—not merely the absence of disease and impairment.3 Although physical well-being contributes to health in the other dimensions, it does not ensure health. Thus emotional and social well-being should be assessed as systematically as is physical well-being in a model of care based on health. Collectively, these domains of health translate into an individual’s capacity to perform activities that enable him or her to participate fully in life.4 The WHO’s definition of health has not been amended since 1948. Although having withstood time, this definition has failed to be incorporated as the primary goal of contemporary health care. Because of widespread immigration, the cultural and ethnic demographic profiles of high-income countries such as those in North America and Europe are changing rapidly. Beliefs, attitudes, values, cultures, ethnicity, and traditions affect health, ill health, and their interactions, including how often individuals seek health care. For example, Asian immigrants to the United States report fewer stress-related and psychological problems than do non-Hispanic Caucasians.5 With increasing time in the United States, however, reports of stress increase for Asian Americans. This may reflect a number of factors: cultural differences in the acceptability of reporting psychological distress (leading to underreporting by members of some cultural groups), sensitization to the definition and the awareness of stress with increasing duration of residence, or the compounding effect of increasing stress in the new culture. How best to reduce racial and ethnic disparities through culturally competent health care is a matter of debate and requires such outcomes as client satisfaction, improved health status, and culturally appropriate management and delivery across racial and ethnic groups.6,7 Since the psychobiological adaptation model was posited over 25 years ago,8 the few models of physical therapy practice that have been reported have included psychosocial and other nonphysiological components.9–11 Psychosocial components include health belief, self-efficacy, and perceived control. The Health Belief Model is useful in appreciating the ways in which belief may affect health, illness, and the responses and reactions to them (Table 1-1).12 Assessment of self-efficacy provides an index of an individual’s sense of mastery over his or her health and well-being. These concepts can be used in a clinician’s practice setting. A few questions can help assess a patient’s perception of susceptibility to risk or a condition. These concepts can provide a basis for health education that includes increasing the patient’s awareness of the effects of lifestyle factors on health and of their consequences. The action necessary to avoid the condition or minimize its risk can be selectively targeted for each individual when the individual’s context is known. Table 1-1 Concepts of the Health Belief Model From Stretcher VJR, Rosenstock IM: The health belief model. In Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors: Health behavior and health education: theory, research and practice, San Francisco, 1977, Jossey-Bass. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health advocated by the WHO interrelates body functions and structures, activity, and participation in life.4 The biomedical model focuses on impairment (i.e., body functions and structures), with less attention to health and wellness, sickness impact, life satisfaction, and quality of life, which reflects an individual’s participation in life and associated activities. One problem that occurs when the primary focus is on the remediation of limitations of function and structure in managing the leading health care priorities of our day (i.e., chronic lifestyle-related conditions) is that such limitations do not necessarily affect activity and participation—the essence of a meaningful life. These relationships need to be evaluated in each case rather than assumed. The integration of health belief and motivational models has been a means of incorporating psychosocial dimensions of care, interventions, and outcomes so as to directly focus on an individual’s limitations of activity and participation. As a result of this paradigm shift, an increasing number of measurement tools are available to assess the dimensions of health. These tools can be categorized as generic, as having general application across individuals and conditions, or as having specific application to a cohort of individuals, based on age, condition, or some other variable (see examples in Chapter 17). Many of these scales have been validated on a subset of these cohort groups. Physical therapists need to be able to use these tools knowledgeably and specifically to assess outcomes in their practices, just as they use conventional tools to assess and evaluate anatomic structure and physiological function. One such measure is the Short Form-36, which evaluates health-related quality of life and has become an established tool for general use and has been adapted cross-culturally.13,14 Such tools can be used to evaluate the individual’s perception of health improvement, which supplements conventional objective clinical measures. People living in high-income countries (e.g., countries in North America and Europe, and some Asian countries) and, increasingly, in countries whose economies are growing are experiencing a paradox: an increase in the negative impact of a more Western lifestyle combined with an increase in advances in biomedicine. Technological and economic advances have been proposed as factors contributing to an obesity-conducive environment.15 The effects of low activity (hypokinesis) and poor nutritional choices on health in Western countries have been reported to be synergistic and partially additive,16 although a potent interaction may exist. The power of nonpharmacological interventions and solutions to affect global health priorities related to chronic lifestyle-related conditions can no longer be considered secondary to pharmacological solutions.17,18 Rather, they may need to be considered foremost. A nationwide, population-based strategy to improve lifestyle is the primary means of improving a country’s overall health and minimizing morbidity and premature mortality from chronic lifestyle-related conditions with the least risk and cost.19–21 Even a modest reduction in cardiac risk factors, for example, could save approximately three times as many life-years as invasive interventions.22 Preserving and maximizing health in the most cost-effective, low-risk, and ethical manner warrant being universal health care priorities in the 21st century to stem the tide of chronic lifestyle-related conditions. Poor nutritional choices and sedentary lifestyles combined with tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption, and stress underpin chronic lifestyle-related conditions in high-income countries, and they pose the greatest threats to public health.23–25 Eight major risk factors related to lifestyle and their documented impacts on health appear in Table 1-2. This trend has given rise to dramatic increases in a relatively newly defined condition, metabolic syndrome, which includes insulin resistance, high blood pressure, elevated triglycerides and cholesterol, and obesity. With industrialization and technological advances, lifestyle-related conditions are on the rise in low- and middle-income countries as well.26,27 Despite their prevalence, however, the WHO has long proclaimed that lifestyle-related conditions are largely preventable.28 Table 1-2 Major Modifiable Risk Factors for Lifestyle-related Conditions *An increased risk of all-cause cancer. Smoking is not only related to cancer of the nose, mouth, airways, and lungs; smoking increases the risk of all-cause cancer. †Partially saturated, saturated, and trans fats are the most injurious to health. ‡Alcohol can be protective in moderate quantities, red wine in particular. Modified from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, 2003; Bradberry JC: Peripheral arterial disease: pathophysiology, risk factors, and role of antithrombotic therapy, Journal of the American Pharmacy Association 44(2 Suppl 1):S37–S44, 2004; Charkoudian N, Joyner MJ: Physiologic considerations for exercise performance in women, Clinics in Chest Medicine 25:247–255, 2004. Atherosclerosis is the major common denominator and contributor to lifestyle-related conditions, including ischemic heart disease (IHD), hypertension, and stroke. Factor analysis supports a two-factor solution for heart disease and possibly for other lifestyle-related conditions: family history (factor 1) and lifestyle factors such as smoking, serum cholesterol, blood pressure, nutrition, exercise, and weight control (factor 2).29 At the population level, choosing health—which includes smoking abstinence along with optimal nutrition and exercise throughout life—can enhance the quality of life, decrease the prevalence of chronic lifestyle-related conditions, and reduce the burden of these conditions on individuals, families, communities, and countries, including suffering and health care costs.30–32 IHD secondary to atherosclerosis continues to be the leading cause of premature mortality and disability in industrialized countries. The prevention and management of risk factors of systemic atherosclerosis should be a primary target of contemporary care for children as well as for adults.33–35 Ischemic cerebrovascular, coronary, and peripheral vascular conditions are manifestations of the same underlying pathological process, blood vessel narrowing caused by atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Smoking, a high-fat diet, and inactivity can precipitate damage to the endothelium and fat deposition within arterial walls. This common pathway has been associated with increased fibrinogen and C-reactive protein, markers of inflammation.36 The focus of biomedical research has shifted to the role of inflammatory mediators and the contribution of low-density lipoproteins to atherosclerosis and away from the concept of degenerative vessel disease. Fibrinogen is an inflammation mediator and a clotting factor. People with cardiovascular disease have high fibrinogen levels, which further increase the risk for thrombosis and manifestations of circulatory disease. Inflammation has been implicated in a growing number of chronic conditions, such as IHD, stroke, asthma, gastrointestinal ulcers, cirrhosis of the liver, Alzheimer disease, cancer, and autoimmune conditions.37,38 Unhealthy lifestyle choices have been thought to contribute to a proinflammatory state, giving rise to low-grade infection in various organ systems and leading to the signs and symptoms associated with various chronic degenerative processes.39 Although this is an important finding, a proinflammatory milieu and inflammation are not the causes of the chronic conditions with which they have been associated but, rather, are precipitating effects of traumas resulting from lifestyle. Lifestyle-related conditions can no longer be considered adult conditions or age-related conditions. Children are exhibiting signs of cardiovascular disease, including arterial atherosclerotic streaking, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obesity.40 Forty years ago, these conditions manifested in adults. With sedentary lifestyles, low activity, and poor nutrition, children are showing the results of accumulated injury to blood vessels and larger body frames and weights. As a consequence, children today are manifesting lifestyle-related conditions earlier than previous generations and are thus expected to die prematurely from these conditions and to have shorter life expectancies than their parents. Throughout their lives, these individuals can expect to have prolonged morbidity associated with these conditions, the secondary complications of these conditions, associated adverse responses to other health complaints, and increased iatrogenic problems (secondary to drugs and surgery).41,42 Health promotion strategies directed toward parents and young children will help to offset the population’s health threat of lifestyle-related conditions. Life expectancy has almost doubled since 1900. The post–World War II baby-boom generation characterizes the demographics of many industrialized countries. This cohort has lived in prosperous times and up to that time was the longest living generation in history. Despite the prosperity seen by the baby boomers, this era was associated with more sedentary lifestyles and access to food products low in nutritional value. Although the manifestations of lifestyle-related conditions are associated with aging, they are not necessary consequences of aging. This is based on cross-cultural comparison studies. Optimal nutrition, exercise, stress control, smoking abstinence, and moderate alcohol consumption, if any, are central to reducing the probability of chronic lifestyle-related conditions and associated disability and maximizing quality of life as people age.43 In particular, increased quality of life with a higher threshold for chronic lifestyle-related conditions and less morbidity toward the end of life is the objective. Figure 1-1 shows the theoretical increase in the threshold of these conditions with healthy lifestyle choices (i.e., not smoking, optimal nutrition and weight control, regular physical activity and exercise, optimal sleep, and reduced stress) and reduced rate of progression of chronic conditions. Ostensibly, the net result is more “life to years” as well as more “years to life.” As primarily a noninvasive health care profession, physical therapy is uniquely positioned to have a primary role in promoting health and wellness, while also preventing, managing, and in some cases, reversing these pandemic lifestyle-related conditions, objectives that commonly coexist because they share a common pathway.44 Integrating health promotion into practice would directly address the ultimate knowledge translation gap in health care (with respect to the benefits of healthy living).45 Indeed, focusing on health promotion, in addition to directly addressing the risk factors and/or manifestations of secondary lifestyle-related conditions, may result in more favorable outcomes for a patient’s presenting problem. Triage of individuals by both noninvasive practitioners and invasive practitioners would constitute a bold initiative in health care. Such triage could establish whether a patient’s complaint is best managed in the short and long term wholly noninvasively, wholly invasively, or by some combination, with a view to weaning the patient off medications or minimizing the medication. Similarly, every effort should be made to avoid surgical intervention and its risks whenever possible (i.e., surgical intervention as a last resort rather than a first resort) by exploiting noninvasive interventions and strategies to restore health and promote lifelong health. When an individual enters the health care delivery system, her or his receptivity to health information is likely to be high. This is a prime opportunity to evaluate risk factors and prescribe a lifelong health plan. The effectiveness of nonpharmacological treatments in the management of chronic lifestyle-related conditions has been well documented, but implementation has been poor.46–48 As noninvasive practitioners, physical therapists have a primary role on the health team, which may include physicians and surgeons (i.e., invasive practitioners), nurses, nutritionists, pharmacists, social workers, psychologists, respiratory therapists, spiritual leaders, and others, depending on the requirements of each case. On a broader level, physical therapists can serve in a multisector capacity as consultants and work alongside health care policy makers, corporate business people, urban planners, and architects in developing healthy and safe homes, workplaces, recreational facilities, and communities. The role of the physical therapist clinician is shifting from hospital-based acute care and private practice to the community, schools, industry, home, workplace, and playing field. Biomedical research that evaluates drugs and surgery often lacks control groups that are otherwise healthy or a comparative group in the research design that includes a potentially superior, noninvasively managed group where feasible. For example, a 12-month exercise program involving selected individuals with stable coronary artery disease has shown superior event-free survival and exercise capacity when compared with individuals who received percutaneous coronary intervention.49 In another study, the mortality rate of individuals with heart disease has been estimated to be reduced by 20% to 25% with cardiac rehabilitation, which is comparable to the results of established therapies such as beta blockers.50 Cardiac rehabilitation is noninvasive; thus it is cheaper and has few side effects. Management is focused on changing negative health behaviors and maximizing lifelong health rather than on simply altering a sign or a symptom. Physical therapists treat individuals with chronic lifestyle-related conditions as either primary or secondary diagnoses. Smoking is currently the leading cause and contributor to chronic conditions and premature death in the United States, with poor diet and sedentary lifestyle anticipated soon to overtake tobacco use.51 Television viewing, an indicator of sedentary living, is associated with obesity and is a marker of cardiovascular disease independent of total reported physical activity.51 As noninvasive practitioners, physical therapists have a responsibility to manage these conditions and their risk factors in all patients so as to prevent or control their physical, psychosocial, economic, and societal impact and to promote health in their practices. By prioritizing health and addressing suboptimal health behaviors, regardless of a patient’s primary complaint, the complaint may be mitigated, the rate and quality of recovery potentially improved, and the potential for recurrence reduced. Fundamental to the principle of evidence-informed practice is the fact that health care providers respond to epidemiological indicators and an understanding of the changing demographics and face of our “village.” Lifestyle-related conditions are the leading killers in our village. Men can expect to live 75 years; women, 82 years.52 Functional capacity, however, is estimated to decrease 10% per decade, and half of this decrement is due to sedentary living. Raising children to be healthy and physically active will promote a generation of healthy adults and will thereby delay their physical dependence by 10 to 20 years. Health care workers with international health organizations are trained to manage the unique needs of their villages. This entails knowing the health priorities of the village and making decisions that positively affect the problems and reduce their impact on the community as a whole. In some parts of the world, a health care worker who focuses on malaria when intestinal parasites are the priority is a hindrance, rather than a help, to that village. Similarly, in our health care climate, physical therapists need to make it a priority to meet the leading needs of their “villages.” Smoking abstinence, good nutrition, weight control, exercise, and stress management are evidence-based noninvasive interventions consistent with the needs of contemporary physical therapy practice; the therapeutic potential and impact of those elements on the health of our village are enormous. For example, each kilogram of weight loss has a dose-dependent effect on health outcomes. Further, as little as 30 minutes of moderately intense activity on most days of the week offsets the deleterious effects of sedentary living.53 With the aging of the people of our village and the signs of lifestyle-related conditions now evident in children and young people, the burden of chronic conditions will be prolonged, particularly as individuals approach the end of life. It has been suggested that life expectancy will plateau or even decrease as a result.42 Indigenous peoples in North America and Australasia have unique health challenges and needs. They tend to be less well educated than the dominant culture, have fewer employment opportunities, experience more violent injuries and deaths, and have poorer health and shorter lives. They have significant health risks because of sociocultural factors and genetic predisposition, such as higher rates of IHD, stroke, type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertension, tobacco use, and alcoholism. Large-scale intervention programs are needed for the Native American population based on studies of the health of its children.54 The past few generations have witnessed a shift from indigenous foods to refined grains and foods high in fat and sugar and from active to inactive lifestyles. These trends have exacted an enormous toll in terms of personal and social health indicators. As individuals age in industrialized countries, their activity levels tend to decline. With relatively long life expectancy in these countries, sedentary lifestyles may prolong end-of-life morbidity. A study of individuals who adhered to exercise programs and those who did not revealed the importance of variables such as self-efficacy, perceived fitness, social support, and enjoyment.55 The results of this study have important implications for urban planning; they can inform the design of healthy communities, as well as individual activity and exercise programs. A study of black Seventh-day Adventists has provided a unique opportunity to isolate the effects of lifestyle on African Americans. Seventh-day Adventists promote spiritual well-being and a healthy diet and lifestyle. As a result, the health of black Seventh-day Adventists is better and the incidence of chronic lifestyle-related conditions is lower than that of African Americans who are not Seventh-day Adventists.56 In addition, based on the results of a study of a large cohort, Mormons tend to be fitter and have fewer risk factors for IHD than do other Americans.57 The physical activity profiles of African American women have been compared with recommendations for moderate levels of activity.58 In this study, findings showed that few subjects met the recommended levels of daily physical activity. Exercise was performed on fewer than the recommended number of days per week and for less than the recommended 8 to 10 minutes per session. Attention to frequency and duration may be particularly important when counseling African American women about regular physical activity. African American women have a higher risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke than do Caucasian American women.59 Based on a cross-sectional study of 399 urban African American women, correlates of physical activity within this cohort were identified. Programs to promote physical activity should address the safety of the physical environment and psychosocial factors. Inactive women with less than a high school education and those who perceive themselves to be in poor health should be considered special target groups. Latina women have a higher risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke than do Caucasian American women; this has been attributed to the higher incidence of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus among Latinas.60 The facilitators and barriers to exercising in this cultural cohort have been examined in a cross-sectional study of 300 Latinas. Physical activity has been reported to be higher in younger women, in married women, and in women who had confidence that they could become more active, who saw people exercising in the neighborhood, and who attended religious services.60 The church was recommended as a suitable community setting for initiating programs that provide women with the knowledge, skills, and motivation to become more active and to transmit this information to others in the community through their families. The impact of gender is being increasingly appreciated in terms of health affliction, access to health care, and physiological responses and psychological reactions to illness.61,62 In a Swedish cohort of older adult individuals, obesity-related health indicators and risk factors were reported to differ in men and women and also to differ on the basis of socioeconomic status.63 In response to cardiac rehabilitation, gender-specific effects on high-density lipoprotein cholesterol have been documented.64 Women demonstrate greater improvement in high-density lipoprotein than do men. Urbanization, modernization, and immigration are affecting global health. Within industrialized countries, indigenous people are moving from rural to urban areas; this is occurring in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and many African countries. Rather than seeing improvements in their health overall, relocated rural people are succumbing to lifestyle-related conditions. Middle-aged black men who move to urban areas from rural South Africa, for example, increase their risk for IHD and stroke.65 One explanation for this observation is increased autonomic reactivity to the stress of relocation; however, other lifestyle factors may be implicated. These patterns have been reported for other groups as well; for example, Mexicans and Asians who move to affluent industrialized countries.66 The typical health advantage for people who move to the West from certain Asian countries, such as Japan, is lost with increasing numbers of years in the new culture.67 The efficacy of the quick fix (drugs and surgery) in the management of chronic conditions, particularly lifestyle-related conditions, is being seriously questioned. With respect to long-term outcomes, noninvasive interventions may often be more successful.68 Premature mortality can be significantly reduced with regular physical activity, optimal nutrition and weight control, and avoidance of smoking.69 Relative to invasive care, noninvasive interventions associated with physical therapy (health education and exercise) are low in cost; yet access to these noninvasive measures is commonly more limited than access to invasive care. Although most people are aware of the positive benefits of healthy choices, what is less apparent to them is that small changes in health behaviors can result in major effect sizes. These effect sizes most often surpass those of medications targeted at a single sign or symptom. In a study of over 23,000 people between 35 and 65 years old, for example, Ford and his colleagues70 showed that over an 8-year period, people who did not smoke, had a body mass index under 30, were physically active for at least 3.5 hours a week, and followed healthy nutritional principles had a 78% lower risk for developing a chronic lifestyle-related condition. Specifically, the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus was reduced by 93%, myocardial infarction by 81%, stroke by 50%, and cancer by 36%. Even if not all four of these health factors were present, the risk for developing one or more chronic lifestyle-related conditions decreased commensurate with an increase in the number of positive lifestyle factors. Should a medication be found to have such potent benefits, it would be hailed as nothing short as miraculous. The goal in health care is to exploit the benefits of lifestyle modification and supplement those benefits with medication only if necessary,71 rather than the other way around (supplementing medication with lifestyle modification). A healthy lifestyle is the treatment of choice for lifestyle-related conditions; it is also the primary intervention for their prevention.72 The translation of these research findings into health care practice is a priority. The risk factors for IHD are well established.73 They contribute to atherosclerotic deposits not only throughout coronary vessels but throughout the systemic arterial vasculature.74 Nonmodifiable risk factors include age, sex, family history, and past history. Modifiable risk factors include increased cholesterol, increased homocysteine, smoking, inactivity, high blood pressure, diabetes, weight, and stress.75–77 Less commonly acknowledged risk factors include elevated C-reactive proteins (markers of inflammation37), sharing a lifestyle with someone who has IHD,78 and having overweight parents.79 Further, a shared lifestyle confers increased evidence of IHD in and health risk for children.80 Other emerging risk factors include passive smoking, level of education, depression, anger coupled with hostility, and social isolation.81,82 Based on epidemiological evidence, a 1% decrease in cholesterol reduces the risk for IHD by 3%, and a long-term reduction in diastolic blood pressure of 5 to 6 mm Hg reduces the risk by 20% to 25%.83 Thus even modest changes can have a sizable impact on health. Most risk factors are associated with behavior choices and can be substantially modified.84 Risk factors for IHD are prevalent in the general population. When a cross section of people in their later middle-age years was screened, atherosclerosis involving the femoral artery affected two-thirds of them.85 Further, a direct relationship existed between the degree of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular and general circulatory health. Individuals with peripheral artery disease have a several-fold increased risk for IHD; thus peripheral artery disease can be considered a marker of systemic atherosclerosis. It is estimated that optimal lifestyle could reduce cardiac events related to atherosclerosis by 70% to 80%. Regular walking has a significant effect on reducing the risk for IHD, as has vigorous activity.86 In men with left ventricular hypertrophy, moderate physical activity reduces the risk for stroke by 49% compared with sedentary men who do not have left ventricular hypertrophy.87 Type 2 diabetes mellitus has been reported to be a strong risk factor (and hypertension a less strong risk factor) for IHD in women when compared with men.88 Self-reported fitness has been reported to be independently related to fewer risk factors for IHD and angiographic evidence of IHD in women undergoing coronary angiography for suspected ischemia.89 Measures of obesity are not independently associated with these outcomes. Thus fitness appears to be more important than body weight for cardiovascular risk in women. Physical activity and fitness warrant detailed assessment. They should be an integral part of the cardiovascular risk-factor stratification, and interventions should aim at long-term increases in physical activity and fitness. Assessment of physical activity and exercise programs should be included in the management of all people, particularly in women and those at risk for IHD. Mediterranean-type diets have been increasingly shown to have multiple health benefits and are superior to the North American diet in terms of food diversity and healthfulness. These diets are high in fish, fresh fruit and vegetables, and multigrains. Mediterranean-type diets are also low in added sugar and salt, and they favor unsaturated vegetable oil over saturated animal fats. When diet-related studies are evaluated, people who consume fish twice a week have a 47% reduced risk for cardiac mortality compared with those who eat fish less than once a month.90 Cereal fiber (two whole-grain slices of bread daily) is associated with a 14% reduced risk for myocardial infarction or stroke. Cereal fiber consumption even later in life is associated with a reduced incidence of cardiovascular disease.91 One alcoholic drink a day is associated with the least number of cerebrovascular abnormalities. Moderately and highly physically intense leisure-time activities predict 28% and 44% lower mortality rates, respectively, compared with little activity. Low, moderate, and high levels of exercise are associated with 30%, 37%, and 53% more years of healthy life, respectively. Aerobic training can reduce serum lipids even in older individuals; high-density lipoproteins increase and low-density lipoproteins decrease.92 With lifestyle change, atherosclerosis can regress and associated cardiac events can be minimized.93–96 Psychosocial factors have been identified as risk factors for IHD. Difficulty in managing anger and hostility is one such risk factor, regardless of whether a person has a type A or a type B personality.97 Stress is a risk factor that can be classified as minor daily hassles or as major negative events. Lipoprotein levels increase with both levels; however, coping style and subjective appraisal of stressors are powerful mitigating factors.98 Cumulative daily hassles may be underestimated in terms of their impact on health compared with major life stressors. After an individual’s first coronary event, avoidance strategies are inversely associated with healthy lifestyles, whereas positive reappraisal and problem solving are directly associated.99 Positive reappraisal and problem solving, program participation, rather than adopting distancing and escape strategies predict a person’s capacity to change lifestyle after a coronary episode. Stress management should consider the type of stressor and help to modify the individual’s coping strategies and interpretation of stressors. The risk for a cardiac event after the first one is high.100,101 Thus there is a high prevalence of repeated revascularization procedures and the prescription of more drugs with increased potency to help offset worsening pathophysiological changes. Ornish102 reported that 194 individuals with previous revascularization procedures avoided repeat procedures for at least 3 years (the duration of follow-up in the study) when they participated in a comprehensive lifestyle-change program. Compared with individuals who also had had a previous revascularization procedure but did not participate in the lifestyle-change program, those who did participate reported a level of angina comparable to that experienced with revascularization. The effects of noninvasive intervention can be considered long term, given their multisystem benefits. Revascularization focuses on the repair of an impairment and does not provide the additional multisystem benefits of the lifestyle-change program. To date, efforts to champion aggressive modification of risk factors have been modestly successful. Optimal control of modifiable risk factors for coronary atherosclerosis, including cigarette smoking, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and sedentary lifestyle are well known to reduce the incidence of IHD and, in turn, revascularization procedures and health care utilization.103 Our major health crisis can be addressed only by means of a system of care committed to health, wellness, aggressive risk-factor prevention, and lifestyle modification. Smoking is the leading cause of preventable death in the United States, as well as the rest of the world.51 Despite the well-documented health hazards, smoking remains prevalent in industrialized and nonindustrialized countries and is estimated to shorten life by 11 minutes for each cigarette smoked.104 Thus smoking cessation is a primary health care goal, as well as a professional goal. (In 1996, the APTA adopted guidelines from the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research [AHCPR], which have subsequently been revised.105) The danger of smoking extends beyond COPD and cancer. Overall morbidity and all-cause mortality, including cancer of organs other than the respiratory tract, are higher in smokers. Of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, COPD is typically among the top killers and is associated with the loss of a million years of life each year.106 In the United States, COPD ranks fourth behind IHD, cancer, and stroke. Long-term smokers have higher incidences of all-cause morbidity and mortality (Table 1-3); thus smoking leads to life-threatening conditions that are systemic and are related not just to the respiratory tract.90 Former and current smokers have 25% and 44% fewer healthy years of life, respectively, compared with lifelong nonsmokers. Smoking cessation is a priority for all individuals, not only those with lung disease, regardless of disease severity.107 Smoking by children is highly associated with parental smoking; thus smoking by adults with young families has become a primary focus of public health initiatives.79 Smoking is the single most important preventable cause of illness and death. Table 1-3 Tobacco Facts and Multisystem Consequences of Smoking Data from National Cancer Institute: Cancer Facts, 2010; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: The health consequences of smoking: a report of the Surgeon General, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2004; Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, et al: Mortality from tobacco in developed countries: indirect estimation based on national vital statistics, Lancet 339:1268–1278, 1992; Twardella D, Kupper-Nybelen J, Rothenbacher D, et al: Short-term benefit of smoking cessation in patients with coronary artery disease: estimates based on self-reported smoking data and serum cotinine measurements, European Heart Journal 25:2101–2108, 2004. Pulmonary rehabilitation has demonstrated sustainability of smoking cessation and other health benefits in individuals with COPD;108 thus its use is warranted as a preventive measure, as well as for the remediation and management of disease.109 Rehabilitation programs have proven efficacy, independent of pharmacotherapy, so they should be considered primary interventions rather than priorities after conventional expensive medical care has failed.110 Only with health coaching and follow-up can these individuals effect lifelong health behavior change to minimize exacerbations, reduce doctor and hospital visits, continue working, and reduce overall morbidity. Innovative smoking cessation programs warrant development so that they have maximal impact in the most significant window of opportunity and stage of readiness of a smoker to quit. One such program consisted of 5 weeks of counseling.111 The mean time to deliver the intervention was 44 minutes. At 1 month, 70% of participants had continued to abstain. The mean cost of the intervention was approximately $50 for each person. Smoking cessation is the most cost-effective intervention for smokers with heart disease in terms of health protection and risk reduction. Further, treatment of hyperlipidemia and referral to cardiac rehabilitation are highly cost-effective per quality-adjusted life-year and are relatively cost-effective per year of life saved. Smoking is an established risk factor for ischemic stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and intracerebral hemorrhage,112 as well as for IHD. The risk is directly proportional to the amount smoked. Risk factor detection and management are the cornerstones of high-impact and high-quality care of cardiovascular disease. Stroke is a preventable tragedy for nearly 750,000 people in the United States annually; hypertension is the most common risk factor.113 Although lowering blood pressure below 130/85 mm Hg is well accepted across ages, the success of blood pressure control has been reported to be less than 25% in the hypertensive population.114 Stroke risk is far from being well controlled despite considerable understanding of its causes, and it remains a major health threat. Risk factors for stroke include previous stroke, hypertension, IHD, atrial fibrillation, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, abnormal ankle-to-brachial pressure index, reduced exercise endurance, retinopathy, albuminuria, autonomic neuropathy, smoking, alcohol consumption, and lack of exercise.113,115–119 Risk factors for hypertension and stroke can be accentuated by smoking, elevated cholesterol, glucose intolerance, inactivity, and obesity.120 In addition to stroke, serious consequences of hypertension include hypertension heart disease and renal disease. Implicated as a cause of stroke is increased sympathetic reactivity.121 In the adult population between 60 and 74 years of age, almost 75% of African Americans and 50% of Caucasians have high blood pressure.122 As with IHD, risk factors for high blood pressure consist of nonmodifiable and modifiable risk factors. Nonmodifiable risk factors include age, sex, race, and other genetic factors. Modifiable risk factors include diets high in sodium and low in potassium, alcohol consumption, reduced physical activity, and being overweight.123 Obesity is a strong predictor of hypertension.124 Although significant reduction of hypertension has been attributed to low-dose thiazide diuretics and beta blockers, the first line of defense to prevent high blood pressure and normalize blood pressure should be nutritional approaches, weight reduction, and regular physical activity and exercise.125 In individuals whose hypertension is controlled, the combination of a Mediterranean diet and physical activity can reduce health risk substantially.126 Like other lifestyle-related conditions, hypertension is increasingly common in American children; thus screening should be included in routine pediatric assessments.127 With respect to nutrition, high sodium and low potassium have been implicated in hypertension and stroke, as have lipids. The National Academy of Science has recently announced that reducing added salt by as little as one-third would reduce hypertension in the United States by 25% (11 million fewer cases). Low plasma vitamin C is associated with a several-fold increased risk for stroke, particularly in men who are overweight and hypertensive.128 A minimal reduction in diastolic blood pressure (5 to 6 mm Hg) reduces the risk for stroke by 35% to 40%.83 Thus weight control; regular exercise; a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole-grain cereals; smoking cessation; and blood pressure control are central to stroke prevention, as well as to the comprehensive management of stroke. Although weight reduction is an essential component of hypertension prevention and management, the protective effect of physical activity may be unrelated to the degree of obesity.129 A 4% to 8% reduction in body weight can reduce blood pressure by 3 mm Hg, and physical activity can reduce blood pressure by 5/3 mm Hg.130 In normotensive African American men, aerobic exercise can attenuate an exaggerated blood pressure response.131 Similarly, normotensive fit African American women have blunted blood pressure responses to experimental stressors.132 One study reported no relationship between physical activity and hypertension, flow-mediated dilation of the brachial artery, or an index of angiogenesis assessed with plasma vascular endothelial growth factor (the latter two being indicators of endothelial dysfunction).133 In this study, however, physical activity was based on self-report in a questionnaire rather than on fitness outcomes, so the results of the study are difficult to interpret. Physical activity and optimal nutrition can reduce the risk for early atherosclerosis, a precursor to stroke, in lifelong nonsmokers.134 Smokers benefit less from this protective effect. Physical activity seems not only to reduce the risk for stroke but also to provide a potent prophylactic strategy for increasing blood flow and reducing brain injury during cerebral ischemia.135 A possible mechanism is augmented endothelium-dependent vasodilation via up-regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase throughout the vasculature. Aerobic exercise three times a week reduces cerebral infarct size and functional deficits in a mouse model and improves endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation.135 Assessment of risk for hypertension is an important component of each patient’s assessment. The management strategy should be based on an analysis of the overall risk assessment rather than on blood pressure alone. The prevention of hypertension requires more than normalizing blood pressure if the deadly manifestations of high blood pressure including IHD are to be avoided. Because of the dire consequences of hypertension, the American Heart Association advocates stringent blood pressure limits—specifically, below 130/85 mm Hg, regardless of age.136 Recommendations by the American Heart Association concerning physical activity and exercise guidelines for survivors of stroke concur that physical conditioning is a primary goal in these individuals, who must contend with both the pathological effects of stroke and the effects of deconditioning.137 Walking as little as 2 hours a week can reduce the risk for stroke by 50%.130 Improved conditioning may help to reduce limitations of activity and participation and hence improve quality of life. The burden of disease and disability and their risk factors may be correspondingly reduced. To affect the health of the population, stroke prevention depends on the dissemination of these well-established and widely available interventions to a large number of people through public health policy. Advice given by a health provider to individuals with stroke for the purpose of prevention of a second stroke can have significant impact. In one study, individuals were simply advised to eat fewer high-fat and high-cholesterol foods and to exercise more.138 Compared with a control group that received no advice, those receiving advice reported fewer days with limited activity, fewer days that “were not good physically,” and more “healthy” days. The results of this study are compelling in that even simple advice by a health care provider can have a major impact on important health behaviors and on potential health outcomes. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a serious multisystem condition that has rapidly become pandemic in Western countries and some other countries where its incidence was previously minimal. In addition to the serious physical and functional consequences of this condition, perceived health status and quality of life are also compromised.139 By 2010, an estimated 250 million people will be affected worldwide.140 Formerly known as adult-onset diabetes, type 2 diabetes mellitus is now being diagnosed in children, predisposing them to blindness, IHD, stroke, renal disease, peripheral neuropathies, vascular insufficiency, and amputations.141,142 Inositol acts as a poison on the membranes of cells in the presence of high blood sugar, and it has been implicated in the deadly systemic consequences of diabetes. The primary consequences include pathological changes to the macro- and microvasculature and to the nerve endings. Impaired glucose tolerance is a marker of vascular complications in the large and small blood vessels, independent of an individual’s progression to diabetes. Early detection of glucose intolerance allows intensive dietary and exercise modifications, which have been shown to be more effective than drug therapy in normalizing postprandial glucose and inhibiting progression to diabetes.143 Diabetic autonomic neuropathy as an independent risk factor for stroke may reflect increased vascular damage and effect on the regulation of cerebral blood flow in individuals with diabetes.115 Individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus have increased risk for cardiovascular disease compared with individuals without diabetes, so strict control is essential. Moderate physical activity (such as brisk walking144) along with weight loss is a powerful combination to reduce the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus, as well as to reverse it. These interventions combined with a balanced diet can reduce the risk for developing diabetes among those who are at high risk by 50% to 60%.86 Cigarette smoking is an independent risk factor for type 2 diabetes mellitus145 and is particularly dangerous for individuals who already have diabetes.141 Metabolic syndrome refers to a virulent and lethal group of atherosclerotic risk factors, including dyslipidemia, obesity, hypertension, and insulin resistance, and it affects some 47 million people in the United States.146 The incidence of the syndrome is increasing and warrants aggressive noninvasive management. Insulin sensitivity is predicted primarily by body mass index, smoking, age, and daily physical activity. Weight reduction counters the effects of metabolic syndrome and may counter the associated hypertension and dyslipidemia as well. Diet and exercise are primary components of the multifactorial approach to preventing and managing this lethal condition. Obesity has been increasing exponentially over recent decades; currently, 61% of the American population is overweight.147 Obesity is becoming a global pandemic that rivals malnutrition as a health priority in some low-income countries,148 and it contributes to health risks for all lifestyle-related conditions. The complications and risks for which each patient should be assessed include IHD, cardiac myopathy, and chronic heart and lung dysfunction; hypertension and stroke; some cancers; insulin insensitivity and type 2 diabetes mellitus; gallbladder disease; dyslipidemia; osteoarthritis and gout; and pulmonary conditions, including alveolar hypoventilation and sleep apnea.149–153 With each kilogram of weight above normal, the risk for hypertension, IHD, and type 2 diabetes mellitus increases proportionately. Obesity is commonly linked with insulin resistance and high blood pressure, which may reflect reduced activity and exercise. Reduced physical activity is a predictor of obesity.154 Insulin resistance associated with lack of exercise in people who are overweight may be further compounded by insulin resistance associated with chronic inflammation observed in fat cells.155 Abdominal obesity, lipid metabolism, and insulin resistance are interrelated markers for coronary artery disease.156 In addition to cardiovascular and general health risk, being overweight affects quality of life.157,158 Comprehensive management of an individual who is overweight and has abnormal blood glucose levels includes normalizing blood glucose (with recommendations for low-glycemic foods and small, frequent snacks rather than infrequent large meals), weight reduction, restricted intake of trans fats and saturated fats, strict blood pressure and lipid control, regular physical activity and exercise, and avoidance of tobacco.159 Nutritional habits during childhood are associated with lifestyle-related conditions in adulthood.160 Obesity in children is associated with parental obesity.79 Maintaining weight within a healthy body mass index range throughout life is recommended for optimal health. Although body mass index may be limited with respect to assessing adiposity because it fails to discriminate between muscle and fat and identify regional adipose depositions, it remains a useful supplementary clinical index.161 Physical therapy has a primary role in preventing and managing overweight and obesity in every client or patient, regardless of age, given obesity’s serious multisystem consequences, psychosocial sequelae, and threat to life participation and satisfaction.162 Cancers associated with the highest mortality rates include lung, colorectal, and pancreatic cancer.163 Smoking has been implicated as a risk factor for many cancers, not only those involving the respiratory tract. The role of lifestyle factors in cancer remission has not been studied in detail. Cancer prevention and rehabilitation have become a specialty area, requiring an integrated knowledge of pathophysiology, psychosocial implications, and management interventions.164,165 Routine assessment of health behaviors and risk factors and healthy living recommendations may help avert the diagnosis of many cancers or mitigate their effects. To date, evidence that walking is an effective strategy to prevent cancer has been best established for colon cancer,86 although breast cancer and prostate cancer have also been reported to be positively affected by regular aerobic exercise including walking.166,167 Osteoporosis and arthritis contribute to considerable morbidity and secondarily to mortality. Because both of these conditions have lifestyle components, a lifestyle risk factor review should be included in every initial assessment to establish a baseline of musculoskeletal health. Moderate levels of physical activity, including walking, are associated with a substantially lower risk for hip fractures in postmenopausal women.168 Thus assessment of both nonmodifiable and modifiable risks is a major component of the health assessment as a means of minimizing morbidity and potential mortality.9 Osteoporosis and associated morbidity, particularly in older age groups, is a serious health issue that warrants monitoring. Establishing baseline information on bone health in every patient is prudent, given the relationship between bone health and lifestyle behaviors (e.g., activity and nutrition—smoking and heavy consumption of meat, alcohol, and coffee). Although older, postmenopausal women have been the focus of bone health studies, other groups are also at risk for osteoporosis and should not be overlooked: older men; inactive children, particularly girls; and individuals with chronic conditions who may be less able to undertake weight-bearing activities and physical activity. In a study of the development of bone mass and strength in girls and young women, only exercise (not daily calcium intake) was associated with bone density and strength.169 This finding stresses the singular importance of bone building in young people to help offset osteoporosis later in life and associated decrement in quality of life. Mental health problems and depression are prevalent in Western society despite its affluence. Based on one descriptive study, individuals with mental health conditions such as schizophrenia tend to have poor physical health and die prematurely from cardiovascular disease.170 Compared with women who have schizophrenia, men with the condition consumed less fruit, vegetables, whole grains, and rice than recommended. Further, the incidence of smoking and obesity in both sexes was higher than in the general population. Cholesterol levels were high and activity levels low. This study suggested cause for concern about both the physical and psychological well-being of individuals with mental health conditions and indicated the need for further investigation of the physical health and well-being of people with mental challenges.

Epidemiology as a Basis for Informing Contemporary Physical Therapy Practice

What Is Health?

Concept

Definition

Application

Perceived susceptibility

One’s belief of the chances of getting a condition

Define the population(s) at risk and their risk levels

Personalize risk based on a person’s traits or behaviors

Heighten perceived susceptibility if too low

Perceived severity

One’s belief of the seriousness of a condition and its consequences

Specify and describe consequences of the risk and the condition

Perceived benefits

One’s belief in the efficacy of the advised action to reduce risk or seriousness of impact

Define action to take—how, where, when

Clarify the expected positive effects

Describe evidence of effectiveness

Perceived barriers

One’s belief in the tangible and psychological costs of the advised behavior

Identify and reduce barriers through reassurance, incentives, and assistance

Cues to action

Strategies to activate “readiness”

Provide how-to information

Promote awareness

Provide reminders

Self-efficacy

Confidence in one’s ability to take action

Provide training, guidance, and positive reinforcement

The Paradox

Lifestyle-Related Conditions

Risk Factor

Cardiovascular (IHD & Hypertension) and Peripheral Vascular Disease

Obstructive Lung Disease

Stroke

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Cancer

Osteoporosis

Smoking

X

X

X

X

X*

X

Physical inactivity

X

X

X

X

X

Obesity

X

X

X

X

X

Nutrition

X

X

X

X

X

High blood pressure

X

X

X

Dietary fat†/blood lipids

X

X

X

X

Elevated glucose levels

X

X

X

X

Alcohol‡

X

?

X

X

X

Life Cycle and Lifestyle-Related Conditions

“First Do No Harm”

Evidence-Informed Practice

Addressing the Health Care Priorities of the Day

Our Village

Principles of Evidence-Informed Practice

The Priorities of Our Village

Ischemic Heart Disease

Smoking-Related Conditions

Type/Area of Effects

Effects and Conditions That Are More Common in Smokers

Mortality from smoking

Tobacco causes 30% of all deaths of people between 35 and 69 years of age

Tobacco reduces a person’s life as follows:

Brain

Stroke

Mouth

Lip and oral cancers

Pharynx and larynx

Cancers of the pharynx and larynx

Esophagus

Cancer of the esophagus

Lungs

Cancer of the lungs

Heart

Ischemic heart disease, hypertension, and circulatory diseases

Chronic lung disease

Bronchitis and emphysema; 90% of deaths from chronic lung disease attributable to smoking

Upper respiratory tract infections and increased days of absenteeism

Gastric and duodenal ulcers

Higher risk in smokers

Bladder and kidney cancers

Higher risk in smokers

Bone

Postmenopausal women who smoke have reduced bone density compared with nonsmokers

Increased risk of bone fractures and delayed healing

Fertility and Pregnancy

Infertility

Increased risk for spontaneous abortions, still births, pre-term deliveries, low-birth-weight babies, and sudden infant death syndrome

Potential developmental and learning delays in children

Hypertension and Stroke

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Metabolic Syndrome

Obesity

Cancer

Musculoskeletal Health

Psychological Health

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Epidemiology as a Basis for Informing Contemporary Physical Therapy Practice