Chapter 49 Eosinophilic Lung Disease

The Eosinophil Leukocyte and Eosinophilic Pneumonia

Diagnosis of Eosinophilic Pneumonia

The diagnosis of eosinophilic pneumonia relies on both characteristic clinical-imaging features and the demonstration of alveolar eosinophilia and/or peripheral blood eosinophilia (Box 49-1). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is a noninvasive alternative to lung biopsy in this setting. The percentage of eosinophils in BAL fluid is less than 2% in normal control subjects, and a differential cell count for eosinophils of 2% to 25% may be found in nonspecific conditions. Therefore, a cutoff value of 25% eosinophils or more in BAL fluid, and preferably 40% or more, is recommended for the diagnosis of eosinophilic pneumonia. The presence of marked eosinophilia in BAL fluid obviates the need for lung biopsy in this disorder, especially when the eosinophils are the predominant cell population in BAL fluid (macrophages excepted). Markedly elevated peripheral blood eosinophilia (greater than 1000/µL and preferably 1500/µL) together with typical clinical radiologic features are highly suggestive of the diagnosis of eosinophilic pneumonia, and BAL may not be always mandatory in such patients, although other disorders may be associated with pulmonary infiltrates and peripheral eosinophilia (e.g., bacterial pneumonia, parasitic pneumonia, infiltrates related to lymphoma). Peripheral blood eosinophilia may be absent at presentation, especially in IAEP and in patients receiving corticosteroid treatment.

Box 49-1

Diagnosis of Eosinophilic Pneumonias

Eosinophilic pneumonia may be separated into that of undetermined origin, which usually may be included within well-individualized syndromes, and that with a definite cause (mainly infection and drug reaction) (Box 49-2). Potential causes must be thoroughly investigated, because identification of a cause may lead to effective therapeutic measures.

Eosinophilic Lung Diseases of Known Origin

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis

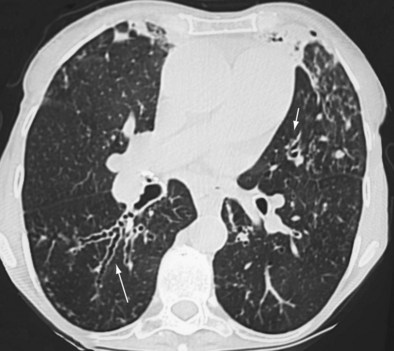

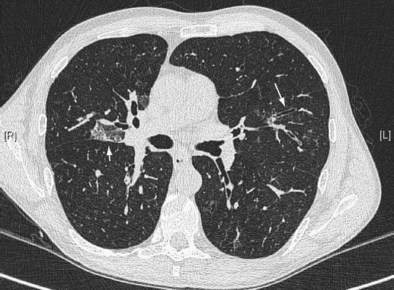

Early ABPA is characterized by fever, expectoration of mucous plugs, peripheral blood eosinophilia with counts higher than 1000/µL, and pulmonary infiltrates caused by eosinophilic pneumonia, or segmental or lobar atelectasis caused by mucous plugging. Chronic ABPA is characterized by asthma, eosinophilia, and bronchopulmonary manifestations including bronchiectasis (Figures 49-1 and 49-2 and Box 49-3). The presence of bronchiectasis on computed tomography (CT) images in a patient with asthma is therefore highly suggestive of ABPA; however, typical proximal bronchiectasis may be absent, and such cases are designated ABPA-seropositive. Centrilobular nodules and mucoid impaction on CT scan (typically characterized by a V-shaped lesion, with the vertex pointing toward the hilum) also are highly suggestive of ABPA. The expectoration of mucous plugs, the presence of Aspergillus in sputum, and late skin reactivity to Aspergillus antigen also are common at this stage; however, Aspergillus is not reliably identified in sputum or BAL fluid samples of patients with ABPA, and positive cultures are not required for diagnosis. The finding of Aspergillus organisms may reflect colonization and thus is not specific for ABPA. Total serum IgE levels of at least 1000 IU/mL constitute a hallmark of ABPA. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is common but is not a required diagnostic criterion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree