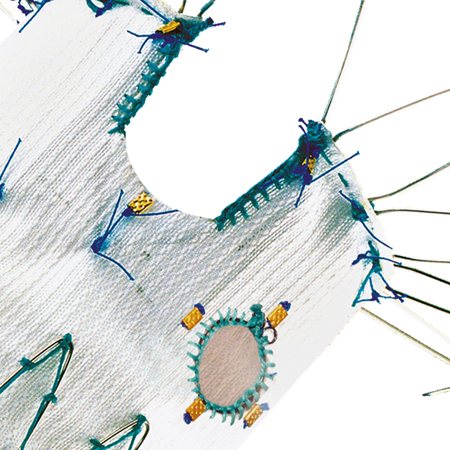

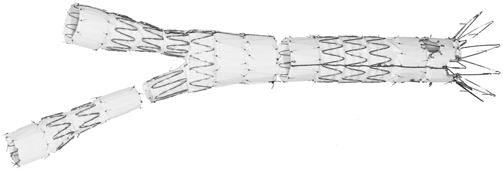

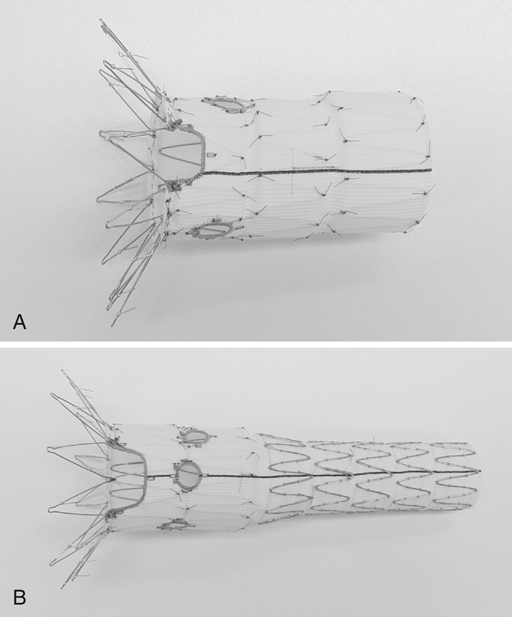

Eric L.G. Verhoeven, Balasz Botos, Wolfgang Ritter and Ignace F.J. Tielliu Fenestrated EVAR stent grafting requires access through both femoral arteries. The procedure can be performed under general or regional anesthesia using an open femoral artery exposure or a percutaneous approach. The stent graft is a composite prosthesis based on the Zenith system (William A. Cook Australia, Brisbane, Australia), which has a self-expanding modular design with an uncovered Gianturco Z-stent (William Cook Europe, Bjaeverskov, Denmark) for proximal fixation in the standard configuration (Figure 1). The first part is a tube graft containing the fenestrations, the second part is a bifurcated device, and the third part is a contralateral limb extension. The tube graft containing the fenestrations is fitted with diameter-reducing ties. The diameter-reducing ties allow repositioning and reorienting of the graft after deployment to facilitate catheterization of the fenestrations and aortic branches. Customization of the stent grafts is based on an individual anatomic configuration. Three types of fenestrations are possible: a scallop in the top of the graft, large fenestration with stent wires crossing, and small fenestrations. The most-used combination is two small fenestrations for the renal arteries and a scallop for the mesenteric artery (Figure 2). Each fenestration is marked by three (scallop) or four (small or large fenestration) radiopaque markers to enable accurate alignment (Figure 3). Each tube graft is fitted with anterior and posterior markers to facilitate orientation during insertion and deployment.

Endovascular Treatment of Pararenal and Suprarenal Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

Technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree