Endovascular Approach to Chronic Mesenteric Ischemia

AHSAN T. ALI and MATTHEW R. ABATE

Presentation

A 62-year-old man underwent an aortofemoral bypass graft (AFBG) for occlusive disease. In the immediate post-op period, he suffered mesenteric ischemia and underwent bowel resection (sigmoid and small bowel). Postoperatively, he developed aortic graft infection and nonhealing groin wounds in the setting of severe malnutrition and failure to thrive. Subsequent workup included computed tomography scan (CTA) demonstrating a stenosis of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and an occluded celiac artery. There was fluid around the graft indicating pan graft infection. Meanwhile, the patient had lost almost 35 pounds, and his prealbumin was 8.1 and albumin was 1.2.

Differential Diagnosis

There is usually little ambiguity about the diagnosis by the time the patient arrives in vascular clinic. Most patients have already undergone a cholecystectomy along with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy, along with further imaging studies such as a CTA.

The hallmark of chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI) is weight loss and postprandial pain. In certain clinical scenarios, the diagnosis can be in question if there is no weight loss. Occult malignancy can be associated with weight loss and “aversion from food” due to nausea. Thus, in patients with a history of smoking and unexplained weight loss, occult malignancy has to be ruled out before embarking on any mesenteric revascularization therapy. Other differential diagnoses to consider include nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia at watershed areas, median arcuate ligament syndrome, and aortic dissection.

Workup

In addition to history and physical examination, nutritional parameters and contrast imaging are essential in diagnosis and preoperative planning. CTA is most commonly utilized and will also demonstrate collateral pathways such as the arc of Riolan and marginal artery of Drummond. Other subtle findings are calcification of the origin of the SMA.

Case Continued

The patient had weight loss and postprandial pain. The preoperative CTA demonstrated severe stenosis of the SMA and occlusion of the celiac artery. The CTA also showed the presence of collaterals between the SMA and the inferior mesenteric artery; mainly the arc of Riolan and marginal artery of Drummond. The patient was scheduled for an arteriogram via the left brachial approach as an initial attempt to revascularize the SMA or the celiac artery.

Surgical Approach

Endovascular revascularization of the mesenteric vessels is indicated in acute or chronic clinical settings. A bypass to the celiac and/or the SMA from a supraceliac approach has the highest patency but comes with significant morbidity and mortality. However, if the patient is at a high risk, then an endovascular approach can be initially utilized as a bridge to an open and more durable procedure. The current trend is an endovascular approach first. Open mesenteric revascularizations are being performed less, and most vascular graduates have been exposed to only a handful of cases during their training. Hence, this trend may very well have to do with the comfort level of the vascular surgeon. However, the authors believe, an initial endovascular approach for CMI serves as a bridge to open surgical therapy especially if the patient is severely malnourished or very high medical risk.

For endovascular treatment of CMI, several things have to be considered: brachial versus femoral approach, type of catheter to engage the lumen, balloon expandable stent versus self-expanding, covered versus bare metal stent, and monorail versus coaxial systems.

Contraindications to Endovascular Approach

There are no absolute contraindications. Occlusions of the SMA with heavy calcifications can be a relative contraindication, especially if the occlusion is up to the middle colic artery.

Celiac vs. SMA or Both

The main objective is to treat the SMA. Celiac artery stenting can be attempted if SMA angioplasty is not possible or can not be done. In a comparative analysis of celiac versus SMA angioplasty and stenting, Ahanchi et al. found the primary patency of SMA interventions to be significantly higher bringing to question the clinical utility of celiac artery angioplasty and stenting. Unlike an open bypass, revascularization of both celiac and SMA is not the norm when attempting endovascular approach.

Angioplasty Versus Stenting

Stenting is recommended as the patency of angioplasty alone is dismal.

Brachial Versus Femoral

A femoral approach is preferred by some because it accommodates a larger sheath and a closure device can be used. For this particular approach, a curved catheter such as a Visceral Select (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) with a “Shepherd hook” is used with a hydrophilic wire. A Glide Cobra (Terumo Medical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) can be used as well. However, a flush occlusion of the SMA usually precludes the femoral approach. The left brachial artery provides a straighter approach but has a higher complication rate. With access via the left brachial artery, the catheter does not need to be reversed; a Vert or MPA 125 are popular choices (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN). This approach can be performed with a cut down in high-risk patients (women, small caliber arteries). Lastly, it also depends on skill set and comfort level of the surgeon. The brachial approach clearly has advantages of torquability and pushability to facilitate crossing occlusions.

Balloon-expandable Versus Self-expanding

Most interventionalists prefer a balloon-expandable stent for accurate placement. However, if an abdominal procedure is planned in the future, a self-expanding stent can be used. It will keep its form and withstand retractor pressure during a subsequent open procedure, whereas the balloon-expandable stent may get crushed. Self-expanding nitinol stents are not as precise. Avoid the usage of more than one stent.

Covered Versus Bare Metal

With covered stents there are four options: Gore ViaBahn (Gore Medical, Flagstaff, AZ), Bard Fluency (Bard, Tempe, AZ), Wall Graft (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA), and iCast (Atrium, Hudson, NH). The first three require a large caliber sheath (7 French or greater) and usually cannot be very precisely placed via the femoral approach. Hence, a cut down of the brachial artery may be necessary. The author prefers a balloon-expandable bare metal or covered (iCast, Atrium, Hudson, NH) stent. These can be deployed using a 6-French sheath. The longer the stent, the more difficult it is to deploy accurately. Anything longer than 40 mm is usually not needed.

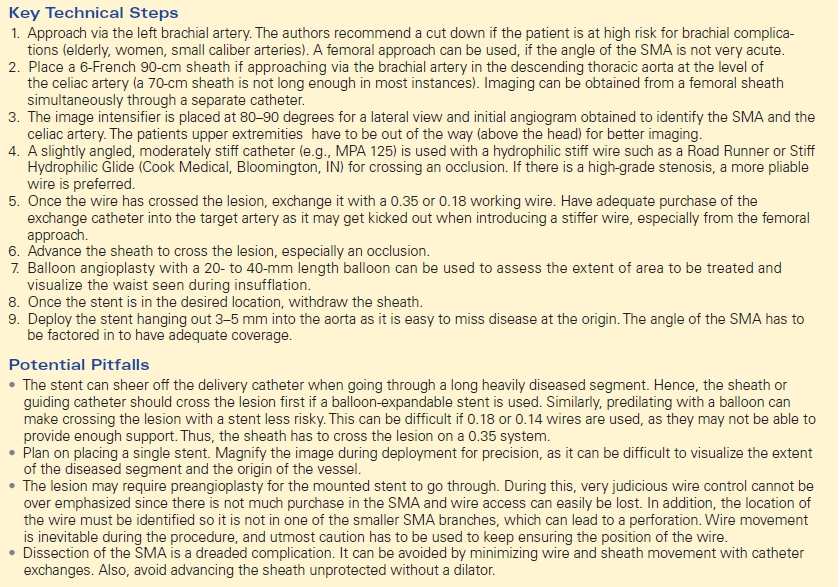

TABLE 1. Key Technical Steps and Potential Pitfalls