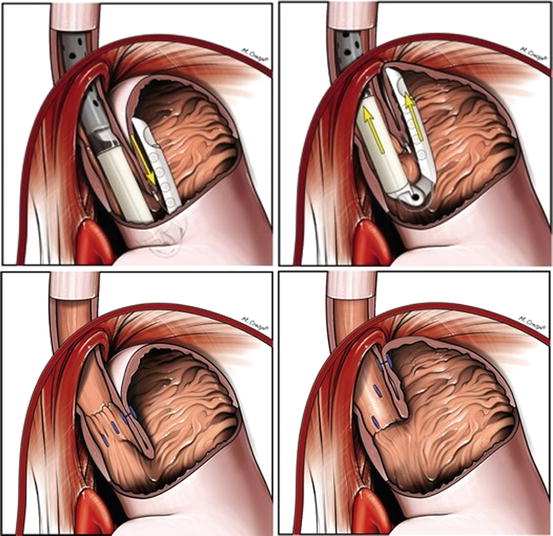

Fig. 10.1

EndoCinch. The Bard EndoCinch (C. R. Bard, Inc., Murray Hill, NJ) delivers a hollow-core needle through a suction capsule that acts to pull the tissue at the squamocolumnar junction into the device. A treasury tag (or “t-tag”) mounted on the end of the suture is pushed through the suctioned tissue, then the t-tag is captured again by the capsule

Research investigating the EndoCinch device has had mixed results. In a randomized sham-controlled trial of 60 patients in the Netherlands, heartburn and quality of life improved after 3 months after EndoCinch as compared to sham, but acid exposure did not change, and 29 % of patients had to be retreated within a year. There were no major adverse events associated with EndoCinch in this trial [15]. A nonrandomized prospective trial of 51 patients comparing EndoCinch and laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication showed a significant improvement in Heartburn Severity Score (HBSS), acid exposure, PPI use, and quality of life after both procedures with a 1-year follow-up. Laparoscopic fundoplication, however, had a significant advantage in both HBSS and acid exposure as compared to EndoCinch. EndoCinch did not have a significant effect on LES pressure or esophagitis. Two episodes of bleeding, one requiring transfusion, occurred after EndoCinch. Postoperative dysphagia was more common in the laparoscopic group [16].

Velanovich and colleagues conducted a nonrandomized trial of 27 EndoCinch and 27 laparoscopic fundoplication patients and found no statistical difference between the two groups in terms of GERD health-related quality of life score (GERD-HRQL) [17]. A multicenter trial following 85 patients that underwent EndoCinch over 2 years showed significant improvement in heartburn frequency score (HFS), PPI use, and acid exposure but failed to show any improvement in LES pressure. One patient required intubation during the procedure, and another experienced melena but did not require transfusion [18]. Another study of 64 patients followed for 6 months after EndoCinch had similar results in terms of improved heartburn without change in manometry or degree of esophagitis. One patient had a perforation that was treated with antibiotics [19]. One study reported a 55 % retreatment rate at 2-year follow-up [20]. Overall, the data for EndoCinch show modest improvement in symptom control and only equivalent or worse rates of PPI discontinuation when compared to laparoscopic fundoplication.

Many variations on endoscopic sewing devices have been developed that have since been removed from commercial use. The NDO Endoscopic Plicator system was approved by the FDA in 2003 and utilized a retroflexed Plicator that retracts the stomach 1.5 cm below the cardia and then deploys a pre-tied full-thickness stitch just below the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) to create a serosa-to-serosa fundoplication. Rothstein and colleagues performed a multicenter prospective randomized sham-controlled trial with 78 patients undergoing the Plicator procedure and 81 undergoing a sham procedure. They showed significant improvement in GERD-HRQ, PPI use, and esophageal acid exposure in the Plicator group versus the sham group, but the follow-up was limited to only 3 months. The Plicator procedure was associated with several complications: pneumoperitoneum (in as high as 39 % of patients), need for intubation, pneumothorax, and minor symptoms such as pain, nausea, dysphagia, and eructation [21]. Ultimately, device malfunctions caused the NDO Plicator to be recalled in 2007.

Other endoscopic suturing devices that are no longer commercially available for the treatment of GERD include the Cook Endoscopic Suturing Device (ESD), the Syntheon Anti-Reflux Device (ARD, Miami, Fl), and the Olympus HIZ-WIZ Device created in Tokyo. These devices failed to show efficacy in several small nonrandomized trials. The Cook ESD, for example, did not produce any significant improvement in manometry, DeMeester score, PPI use, or quality of life in two small case series [22, 23].

Esophyx by EndoGastric Solutions (Redwood City, WA) is the newest endoscopic suturing device that was approved for use by the FDA in 2007. Esophyx uses permanent polypropylene “H” fasteners to create a serosa-to-serosa fundoplication. This device has undergone two major transformations since its initial prototype. The first version, termed the endoluminal fundoplication (ELF) used the TIF1 device that created a gastrogastric wrap at the GEJ. The second version, TIF2, attempted to replicate a laparoscopic fundoplication by placing the full-thickness H fasteners 3–5 cm above the GEJ to create an esophagogastric fundoplication. Cadiere and colleagues first published their experience with ELF in 2006 in a small trial of 19 patients comparing ELF to laparoscopic fundoplication as well as endoscopic plication. Laparoscopy had the best results in terms of PPI discontinuation (92–96 %) and pH normalization (91–96 %) among the three groups at 6 months. Eighty percent of patients treated with ELF were off PPIs at 6 months, and 67 % had normal pH. Endoscopic plication had the worst results with 74 % off PPIs and only 30 % with normal pH after 6 months [24]. After 1-year follow-up in 16 patients, 82 % of patients treated with ELF had discontinued PPIs, 63 % had normalized pH, and 53 % had over a 50 % improvement in HRQL [25]. The same group then published a larger multicenter prospective feasibility study in 2008 that followed 79 patients for 1 year. They stratified their subjects by Hill grade, and 21 who maintained a Hill grade 1 valve had improved results in HRQL over the entire group. They did report two incidences of perforation and one post-procedure bleed requiring transfusion and a second endoscopic procedure [26]. At 2-year follow-up on 14 of these patients, the same group reported that 29 % had no symptoms of heartburn or regurgitation, and 21 % continued to use PPIs (Fig. 10.2).

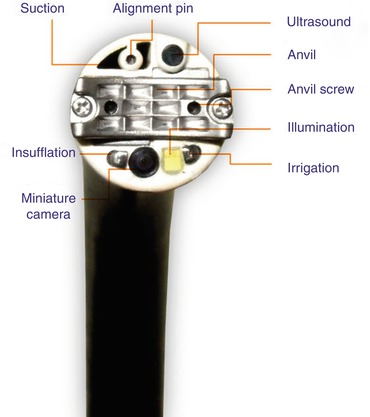

Fig. 10.2

Esophyx. Esophyx by EndoGastric Solutions (Redwood City, WA) is a transoral incisionless fundoplication device that uses permanent polyproplylene “H” fasteners to create a serosa-to-serosa fundoplication

Several other small trials reported slightly decreased efficacy and a similar safety profile as Cadiere with both TIF 1 and TIF2 [27]. One prospective trial of 20 patients showed reduction of hiatal hernia in 61 % of patients on post-procedure endoscopy [28]. Hoppo et al. reported more disappointing results in a small trial of 19 patients, of whom 10 had TIF failure requiring laparoscopic fundoplication [29]. A number of severe complications were reported, including several bleeds and perforations.

A larger retrospective study of 110 patients yielded more promising results after a 7-month follow-up: 93 % of subjects had discontinued PPIs, 79 % reported no symptoms, and only 4 % required a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication after TIF [30]. Svoboda and colleagues conducted a randomized control trial comparing TIF and laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication in 16 and 18 patients, respectively (they initially included the Plicator but stopped recruiting for that arm when it was removed from commercial use). Both TIF and laparoscopic fundoplication groups yielded equivalent results, but the TIF group had a significantly shorter hospital stay [31]. Bell et al. reported a multicenter prospective trial of 100 consecutive patients undergoing TIF in which they found a significant improvement in GERD-HRQL, regurgitation, and heartburn scores. They also reported that 80 % of patients were off PPIs after TIF, whereas 92 % required PPIs before the procedure [32]. Transoral incisionless fundoplication has been shown to be safe in many observational studies, but further long-term, large, randomized, sham-controlled trials are required to prove its efficacy. Like most of the trials mentioned in this chapter, these trials are underpowered and do not have longer than a 1-year follow-up. Another criticism is that the device has undergone revisions, so its current model has limited published data. Of the endoscopic suturing devices, Esophyx, however, has the greatest promise in terms of finding a role in the treatment of GERD (Fig. 10.3).

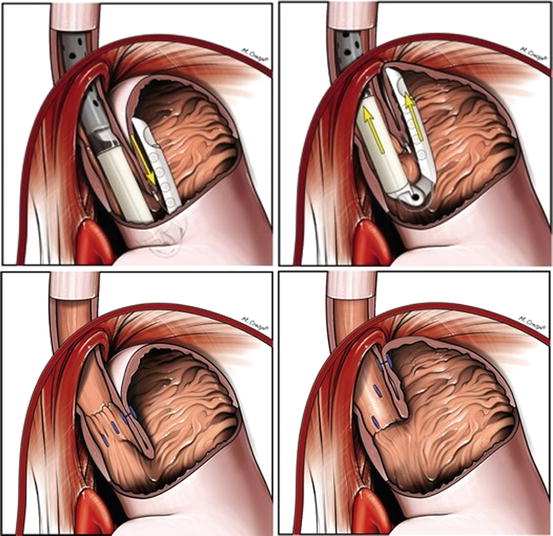

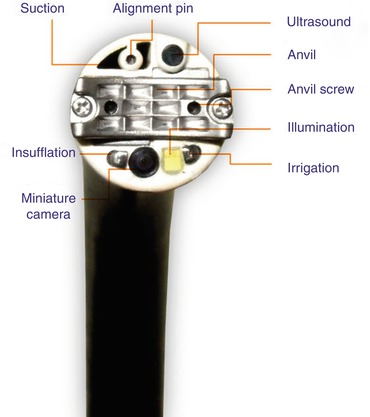

Fig. 10.3

SRS endoscopic stapling system. SRS (Medigus in Tel Aviv, Israel) is an endoscopic stapling system that uses endoscopic ultrasound guidance to place a cartridge of staples through the tip of the retroflexed endoscope through the cardia into the esophagus

Medigus in Tel Aviv, Israel has developed the SRS endoscopic stapling system that uses endoscopic ultrasound guidance to place a cartridge of staples through the tip of the retroflexed endoscope through the cardia into the esophagus 2–3 cm above the GEJ. The ultrasonic probe allows the endoscopist to ensure that the appropriate tissues are being plicated. The staples are fired against an anvil that is deployed through the tip of the endoscope and is temporarily screwed in place. Once the staples fire, the screws are withdrawn, and the scope is extended and removed. This technology is currently undergoing investigational studies and is not yet approved for commercial use [33].

No rigorously tested option currently exists to address hiatal hernias endoscopically, so patients with any large or fixed hiatal hernias should not be offered an endoscopic anti-reflux procedure. Ihde and colleagues did develop a hybrid TIF and laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair with posterior cruroplasty in 48 patients with hiatal hernias >3 cm, but they did not stratify their results into TIF alone versus TIF with laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair [34].

Injections and Implants

Researchers have designed several modalities of injections of both polymers and implants into the distal esophagus in an effort to reinforce the reflux barrier by increasing lower esophageal pressure. None of these designs, however, remains on the open market currently for clinical use due to reports of serious complications and lack of efficacy.

Radiofrequency Ablation

The goal of radiofrequency ablation is to decrease the compliance of the LES. Radiofrequency ablation, such as Stretta (Mederi Therapeutics, Greenwich, CT), works by inserting small needles that conduct radiofrequency energy into the LES. The procedure then creates coagulative necrosis and eventual fibrosis of the sphincter. This technique is the most extensively studied endoscopic modality.

Technique

The procedure was initially approved by the United States FDA in 2000. The Stretta device deploys a balloon within a basket fastened to a guidewire through a flexible endoscope. The endoscopist centers the balloon 1 cm above the Z line and inflates it, which deploys four electrodes radially out into the muscular layer of the esophagus. This step is then repeated once more after deflating and rotating the device 45° to apply thermal energy to eight spots 1 cm above the Z line for 1 min intervals. This procedure is then repeated six times at half-centimeter increments down to the squamocolumnar junction and the cardia. Each electrode is designed to heat the tissue to 85° with an impedance monitor to keep temperatures from exceeding 100 °F. The procedure generally lasts between 40 and 60 min. The maximum effect is thought to occur 2–6 weeks after the procedure. A second postulated benefit of Stretta is the interruption of vagal afferent fibers, which could decrease the pain of heartburn and the regulatory feedback that would have signaled for relaxation of the LES (Fig. 10.4).

Fig. 10.4

Stretta. Stretta (Mederi Therapeutics, Greenwich, CT) works to thicken the gastroesophageal junction by inserting small needles that conduct radiofrequency energy into the lower esophageal sphincter musculature

Stretta became the most frequently used endoscopic treatment of GERD early after its FDA approval. Endoscopists used it in over 10,000 patients, and it has been tested in several randomized, sham-controlled trials with modest results and short-term follow-up.

The first randomized, double-blinded, multicenter sham-controlled trial was published by Corley et al. in 2003 [35]. They randomized 35 patients to RF and 29 to a sham procedure and found a significant decrease in mean heartburn and HRQL scores at 6 months in the RF group. Symptom improvement persisted after 12 months. They did not find a significant improvement in PPI use, acid exposure, LES pressure, or healing of esophagitis. There were no major complications associated with the procedure. Aziz and colleagues conducted a multicenter, randomized sham-controlled trial of 36 patients with GERD. They randomized 12 patients to receive one RF treatment, a second RF treatment if GERD-HRQL scores had not improved over 75 %, or a sham procedure. They followed their patients for a year and found that both the single and double RF treatment groups had significantly improved GERD-HRQL scores and 50 % had discontinued PPIs. Two patients had significant delayed gastric emptying, but there were no other severe complications [36].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree