73 Effects of Exercise on Cardiovascular Health

Primary Prevention

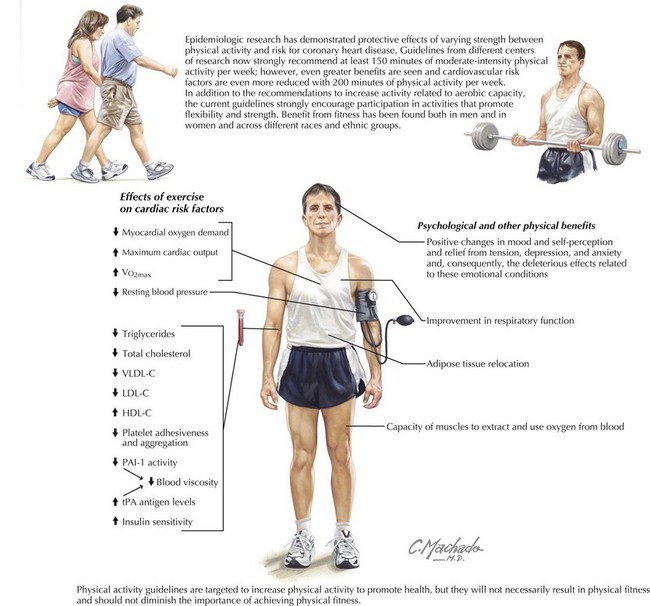

There is a strong inverse relationship between physical activity and the risk of coronary disease and death. Across studies there is an estimated 30% risk reduction in all-cause mortality, comparing the most physically active subjects with the least active subjects. Similar CV benefit from fitness also exists in both sexes and across different races and ethnic groups (Fig. 73-1). The inverse dose-response relation for total volume of physical activity is curvilinear, meaning that those with the lowest physical activity levels have the largest risk reduction with increased physical activity. Several studies in men support a role for physical activity in reducing the risk of mortality. In nonsmoking, retired men aged 61 through 81 years who had other risk factors controlled, the distance walked daily at baseline inversely predicted the risk for all-cause mortality during a 12-year follow-up. Of 10,269 Harvard alumni born between 1893 and 1932, those individuals who began moderately vigorous sports between 1960 and 1977 had a reduced risk of all-cause and CHD-related death over an average of 9 years of observation compared with those who did not increase sports participation. This finding was independent of the effects of lower BP or lifestyle behaviors related to low cardiac risk, such as cessation of smoking and maintenance of lean body mass. Data on the leisure-time physical activity levels of men participating in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) support a reduction of risk for all-cause and CHD-related fatalities when leisure time is spent doing moderate or high (as compared with low) levels of physical activity. The effect was retained when confounding factors, including baseline risk factors and MRFIT intervention group assignments, were controlled. Mortality rates for the high and moderate physical activity groups were similar. The Lipid Research Clinics Mortality Follow-up Study found that men with a lower level of physical fitness, as indicated by heart rate (HR) during phase 2 (submaximal exercise) of the Bruce Treadmill Test, are at significantly higher risk for death due to CV causes within 8.5 years as compared with men who are physically fit.

Secondary Prevention

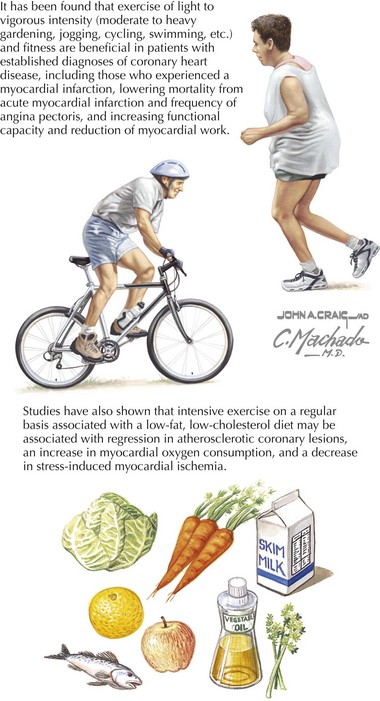

Recent studies have conclusively demonstrated that exercise and fitness are as beneficial for patients with an established diagnosis of CHD as for those who do not have known CHD (Fig. 73-2). In subjects with higher levels of physical activity, there is a 20% to 35% lower risk for CV disease, CHD, and stroke compared with those with the lowest levels of activity. In a large study of men with established heart disease, regular light to moderate activity (such as 4 hours per week of moderate to heavy gardening or 40 minutes per day of walking) was associated with reduced risk of all-cause and CV mortality compared with a sedentary lifestyle. Another large study assessed men’s health status and physical fitness during two medical examinations scheduled approximately 5 years apart. Men who were unfit at both examinations (baseline and 5 years later) had the highest subsequent 5-year death rate (122/10,000 man-years). The death rate was substantially lower in initially unfit men who improved their fitness (68/10,000 man-years) and lowest in the group who maintained their fitness from the first to the second examination (40/10,000 man-years). The mortality risk decreased almost 8% for each minute that the maximal treadmill exercise time at the second examination exceeded the baseline treadmill time. These results were retained when subjects were stratified by health status, demonstrating that unhealthy as well as initially healthy individuals benefited from exercise fitness.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree