Chapter 17 EBUS-TBNA of a Left Lower Paratracheal Node (Level 4 L) in a Patient with a Left Upper Lobe Lung Mass and Suspected Lung Cancer

Case Description

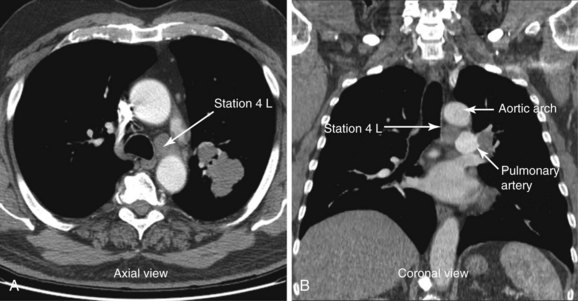

A 72-year-old man with 40–pack-year history of smoking presented with chronic cough. Computed tomography of the chest showed a 2.8 × 1.7 cm left upper lobe mass and a 1.57 cm short diameter left lower paratracheal lymph node (Figure 17-1). The patient was referred for diagnosis and staging. He had a history of COPD (post bronchodilator FEV1 was 58% predicted) and stable angina pectoris treated medically by his cardiologist. On chest auscultation, decreased air entry bilaterally and prolonged exhalation were noted. He was independent in his daily activities but performed them with effort. Karnofsky performance status was 80. Resting and two-dimensional dobutamine stress echocardiography was normal. He lived with his wife at home, desired a prompt diagnosis, and was willing to consider all available treatment options.

Discussion Points

1. Describe the diagnostic yield of EBUS-TBNA versus conventional TBNA and EUS-FNA at station 4 L.

2. Describe how the coronal view of a computed tomography scan can be used to help plan EBUS-TBNA.

3. Describe endobronchial sonographic findings, including adjacent vascular structures at and around lymph node station 4 L.

Case Resolution

Initial Evaluations

Physical Examination, Complementary Tests, and Functional Status Assessment

This patient had decreased air entry bilaterally and prolonged exhalation, consistent with his obstructive ventilatory impairment detected on spirometry. He had grade II functional status based on the World Health Organization scale, specifically, mild limitation of physical activity was noted; no discomfort was reported at rest, but normal physical activity caused increased symptoms.1 Other measurement instruments that can be used to accurately assess impaired health, perceived well-being, dyspnea, and quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, the Borg Baseline Dyspnea Index (BDI), and the modified Medical Research Council (MRC) Dyspnea Scales.2

Results from prospective studies of COPD patients with a mean age of 65 years and a mean value of post bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of 44% of the predicted value show that the all-cause mortality rate is 12% to 16% at 3 years.3 Our patient, however, additionally had a lung nodule, ipsilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and a positive smoking history. These findings are highly suspicious for primary lung carcinoma. If non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) were diagnosed, the primary tumor size would be staged as T1; in conjunction with positive N2 nodal staging (ipsilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy), this patient would be staged clinically as having IIIA disease with an estimated 5 year survival of 19% and a median survival of 14 months despite treatment.4 Because his risk of dying from cancer far outweighs that of dying from COPD, prompt diagnosis, staging, and treatment of his lung cancer are warranted.

Survival estimates are critical factors in patient and physician decision making in all phases of cancer diagnosis and treatment. These estimates are not perfect and of course may not apply to the particular “individual” faced with a cancer diagnosis. One measure that has been used to predict survival and consequently has been used as an entry criterion for oncology clinical trials is performance status. The Karnofsky Performance Scale, for example, is a commonly used general measure of functional impairment that allows comparison of the effectiveness of various therapies and prognosis considerations in individual patients: The lower the score, the worse the chance of survival.5

Comorbidities

This patient had COPD with FEV1 of 58% predicted (moderate; Gold Initiative on Obstructive Lung Disease [GOLD] stage II). He was taking tiotropium 18 mcg/day and albuterol by metered dose inhaler (MDI) as needed. He had stable angina pectoris managed medically with nitrates and calcium channel blockers. The patient had no signs or symptoms of other illnesses. Careful examination and review of systems are warranted because COPD is linked to many comorbid conditions such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, obstructive sleep apnea, psychiatric illness (e.g., depression, anxiety), and cognitive decline, which could preclude or complicate interventions provided under general anesthesia.6,7

Support System

Our patient was married and lived with his wife, who was very supportive. Cancer, as suspected in this patient, is often considered a “family matter” with significant psychological and emotional impact on family members.8 Because significant others are often involved in caregiving to a considerable extent during a patient’s illness, involvement of family members in discussions about diagnosis and prognosis is warranted. Additionally, health care providers should be concerned about the caregiver’s health because several investigators have found that caregiving, although it is not always judged to be a negative experience, can contribute to mental and physical ill health and can have a negative impact on social functioning.9

Patient Preferences and Expectations

Although increasing emphasis is now placed on patient empowerment, results of studies show that many patients do not wish to be involved in decisions about their own care. Patient preferences regarding involvement in decision making vary with age, socioeconomic status, and illness experience, as well as the gravity of the decision. Evidence suggests that even if patients wish to be informed about their illness and treatment alternatives, they might not wish to be actively involved in making the treatment decision.10 Therefore the distinction between providing information, evaluating the information given, and taking responsibility for deciding on treatment may be important. In our case, the patient explicitly asked that all information and alternatives be discussed with both him and his wife, so they could make medical decisions together.

Procedural Strategies

Indications

Tissue diagnosis and sampling of station 4 L (left lower paratracheal node) for staging purposes were warranted because mediastinal lymph node involvement is found in approximately 26% of patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer.11 Sampling of the 4 L lymph node station is important because the presence of mediastinal lymph node metastasis remains one of the most adverse prognostic factors in NSCLC. This tumor can be subclassified as IIIA3 with significant implications for additional management decisions. This is the largest subgroup of IIIA NSCLC patients and consists of patients with clinical ipsilateral lymph node invasion demonstrated by minimally invasive techniques or noninvasive imaging. Patients are often considered resectable or marginally resectable, depending on the number and the location of the lymph nodes involved.12 However, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) states that in NSCLC patients with stage IIIA-N2 disease identified preoperatively, induction therapy followed by surgery is not recommended, except as part of a clinical trial. Furthermore, although the use of any induction chemotherapy followed by surgery in stage IIIA lung cancer appears feasible, published data do not support this treatment as the standard of care in the community.13 In fact, concomitant chemoradiation is increasingly becoming the standard of care in selected patients in clinical stage IIIA3 with a good risk profile, that is, low comorbidity, good performance and pulmonary function, and adequately staged disease.12

Although imaging studies are helpful for identifying lung parenchyma and mediastinal abnormalities, they do not provide a tissue diagnosis. Flexible bronchoscopy would allow complete airway inspection to ascertain the absence of endobronchial lesions, to potentially obtain samples from the lung mass itself, and to sample the mediastinal lymph node at the same setting. This could be done with the use of conventional transbronchial needle aspiration; however, the use of EBUS-TBNA significantly increases diagnostic yield (96% vs. 41%) at the level 4 L region compared with conventional sampling techniques.14,15 By sampling station 4 L, both diagnosis and staging can be accomplished during a single procedure. Complete sonographic mediastinal lymph node assessment is warranted, however, because the tumor may be upstaged to N3 (stage IIIB), in case EBUS identifies contralateral lymph nodes and aspirates are positive for malignancy.16 One study showed that compared with radiologic staging, EBUS-TBNA downstaged 18 of 113 (15.9%) and upstaged 11 of 113 (9.7%) patients.17 Therefore ultrasound examination is done in a stepwise fashion, usually beginning at the highest-level node in relation to the lung mass in staging procedures: Contralateral lymph nodes, when identified, are sampled first and are immediately stained and read by an on-site pathologist. If no malignant cells are seen, subcarinal or ipsilateral lymph nodes are sampled. All aspirates are stained immediately for rapid on-site interpretation; aspirates are obtained until a preliminary cytologic diagnosis of malignancy is given, or until the cytologist determines that an adequate quantity of representative tissue has been obtained (usually four aspirates per lesion).18 For this patient, if complete EBUS mediastinal and hilar evaluation reveals no contralateral nodes, the CT-documented 4 L node should be sampled.

Contraindications

No absolute contraindications to EBUS-TBNA were noted. This procedure is often performed under general anesthesia, which in our patient could predispose to myocardial ischemia as the result of volume shifts and increased myocardial oxygen demand from elevations in heart rate and blood pressure. Patients with major cardiac predictors for anesthesia risk such as unstable coronary syndrome, decompensated heart failure, significant arrhythmia, and severe valvular disease warrant intensive management, which may lead to delay in cancellation of an operative procedure. Other clinical predictors that require careful assessment include a history of ischemic heart disease (as seen in our patient), diabetes mellitus, compensated heart failure, and renal insufficiency. It is noteworthy that diagnostic endoscopic procedures such as bronchoscopy are considered low risk with a reported rate of cardiac death or nonfatal myocardial infarction of less than 1%; therefore preoperative cardiac testing usually is not necessary.19 The negative stress test performed several weeks earlier was reassuring because of its high negative predictive value (90% to 100%) for postoperative cardiac complications.20

Expected Results

In one small study, the diagnostic rate of EBUS-TBNA for station 4 L was equal to that of conventional TBNA (72% vs. 71%), but lymphocytes (indicative of an adequate sample) were more often present on EBUS-TBNA specimens (82% vs. 71%).21 Several larger studies, however, have shown high diagnostic yields of 88% to 96% with EBUS for station 4 L.14,22,23

Team Experience

Although the yield of EBUS-TBNA has generally been reported to be as low as 70% for all lymph node stations,24 it has become standard practice in most institutions that can offer it. An experienced team of doctors and nurses familiar with the techniques and the equipment is necessary. On-site cytology is preferred to provide immediate diagnosis, or at the least to know whether representative samples are being obtained. However, many bronchoscopists do not use rapid on-site cytologic examination because of cost, logistics, and organizational issues, stating instead that because the operator visualizes nodal sampling, immediate cytology is not necessary. On the other hand, having an immediate result of malignancy might increase the yield of the procedure and prevent the need for additional specimens from other nodal sites, thus potentially decreasing the time required for the procedure and potentially the associated complications. This issue continues to be debated within professional circles. A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that on-site evaluation of cytologic specimens had the highest pooled sensitivity at 0.97 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.94 to 0.99); however, because of potential heterogeneity, when pooled sensitivity was compared with that of other subgroups, no statistical significance was found (P > .05).25 In addition, for pathologists, this is a relatively time-consuming procedure, with a mean of 22 minutes spent on an average of three passes performed, with six slides prepared per lymph node site.26

Risk-Benefit Analysis

EBUS-TBNA has a high yield and is a safe same-day procedure.25 One serious complication (pneumothorax requiring chest tube drainage) was reported in a meta-analysis of 1299 patients. Cough and the presence of blood at the needle puncture site are infrequent.27 Even when performed by a single individual using moderate sedation in a single center, patient satisfaction was high, and no complications occurred that might have compromised diagnostic yield.28

Anecdotal reports show evidence of clinically significant bacteremia and polymicrobial pericarditis with tamponade physiology after EBUS-TBNA; these complications were considered to be caused by direct inoculation of oropharyngeal flora into mediastinal tissue during full EBUS-TBNA with needle extension to 3.6 cm.29 Some investigators have suggested that contamination of the TBNA needle by oropharyngeal flora is common and may predispose patients to clinically significant infection, although this occurs rarely.30 Results from a prospective study document the presence of bacteremia, confirmed by blood culture within 60 seconds of EBUS-TBNA, in 7% (3/43) of patients, compared with 0% to 6% rates following routine bronchoscopy, but no clinically significant infections have been described (none of the three bacteremic patients had clinical features suggestive of infection within 1 week of EBUS-TBNA). Bacteremia, universally caused by oropharyngeal commensal organisms, is considered by some investigators to be the likely result of insertion of the bronchoscope itself. Investigators postulate that as the bronchoscope traverses the naso-oropharyngeal region, the working channel becomes contaminated. As a result, when the transbronchial needle passes through the working channel, it becomes contaminated and can potentially inoculate the sampled tissue. Although the needle designed for the EBUS scope has an outer sheath, which could minimize sample contamination, this sheath is still passed through the working channel. When the needle is advanced at the site of interest, it is passed through the distal end of this sheath and could become contaminated. In addition, needle penetration depth may contribute to contamination and infection, especially if the tip of the fully extended needle is out of the scanning plane, and the pericardium or vessels can be violated but not visualized.29

Diagnostic Alternatives

1. CT-guided percutaneous needle aspiration of the left upper lobe nodule could be performed because the diagnostic rate (91%) is high. This would not provide information on staging, is associated with increased risk for pneumothorax (5% to 60%),31 and provides no information regarding airway lesions and potential resectability. If cancer were diagnosed, mediastinal sampling would still be warranted for staging purposes.

2. EUS-FNA (endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration) could be performed because the 4 L lymph node station is accessible via the esophagus. Overall reported sensitivity is 81% to 97%, and specificity is 83% to 100%.32 For station 4 L in particular, EUS-FNA has a diagnostic yield similar to EBUS-TBNA.23 Some might argue that bronchoscopy would still need to be performed to identify possible airway abnormalities. Rates of bacteremia following upper EUS are similar whether or not FNA is performed and are equal to those seen in routine gastroscopy (6%).33

3. Mediastinoscopy is still considered the gold standard and may be recommended if endoscopic sampling of station 4 L is negative for malignancy and is otherwise nondiagnostic.14 This invasive procedure is performed in the operating room with the patient under general anesthesia. It has associated morbidity and mortality of 2% and 0.08%, respectively.34 Mediastinoscopy has a specificity of 100% and offers good access to lymph node stations 2, 4, and 7, but access to posterior and inferior mediastinal nodes is limited, which explains its overall sensitivity of 80% to 90%.31

4. Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) is another invasive alternative but provides access to ipsilateral nodes only and has 75% sensitivity overall.35 Its benefits include access to inferior mediastinal nodes and definitive lobar resection at the same time if nodes are negative.

Cost-Effectiveness

In two separate decision-analysis models, EUS-FNA + EBUS-TBNA and conventional TBNA + EBUS-FNA were more cost-effective approaches than mediastinoscopy for staging patients with NSCLC and abnormal mediastinal lymph nodes on noninvasive imaging.36,37 The strategy of adding EUS-FNA to a conventional lung cancer staging approach (mediastinoscopy and thoracotomy) reduced costs by 40% per patient.38 The two procedures (EUS-FNA and EBUS-TBNA) can be performed with the use of a dedicated linear EBUS bronchoscope in one setting and by one operator. Procedures are complementary and their combined use provides better diagnostic accuracy than is attained with either procedure alone.39 This approach may reduce costs and enhance efficiency if one person can perform the combined procedure; simultaneously scheduling two skilled endoscopists with different subspecialties is often difficult.

EBUS-TBNA may actually increase health care costs if done in low-volume centers by inexperienced operators.40 In fact, start-up costs are significant because of the need for training (participation in national and international hands-on workshops), equipment costs, and the risk that costly repairs will be needed in cases of instrument damage.41

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree