Chapter 19 EBUS-Guided TBNA for Isolated Subcarinal Lymphadenopathy (Station 7)

Case Description

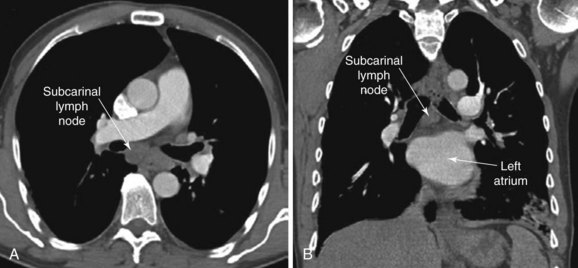

The patient is a 51-year-old male with a 10–pack-year history of smoking. His past medical history includes COPD (FEV1 60% predicted) controlled on tiotropium and albuterol inhalers and right toe amputation for melanoma 3 years earlier. A surveillance chest CT ordered by his oncologist showed a 2.5 × 2.7 cm subcarinal lymph node and no other abnormalities (Figure 19-1). The PET scan showed increased activity (SUV max 6) in the subcarinal node but no evidence of other thoracic or extrathoracic abnormalities. His physical examination was normal. He lives alone and is extremely concerned about a possible recurrence of melanoma. He has been referred for convex probe EBUS-guided TBNA.

Discussion Points

1. Describe how the coronal view of a computed tomography scan can be used to help plan the procedure in this patient.

2. Describe the yield of EBUS-guided TBNA versus conventional TBNA for sarcoidosis.

3. Describe the clinical implications of granulomatous inflammation detected on an EBUS-guided TBNA specimen.

4. List six sonographic criteria of morphology that can be used to describe mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes.

Case Resolution

Initial Evaluations

Physical Examination, Complementary Tests, and Functional Status Assessment

Chest computed tomography (CT) showed a large* 2.5 cm subcarinal lymph node with no associated pulmonary nodules, masses, or infiltrates. Although variations in normal node size are significant, depending on the location of the node, by convention, the upper limit of normal for mediastinal lymph nodes is considered to be 1 cm in the short axis, except in the subcarinal region, where an upper limit of 1.5 cm is generally used.1 Micrometastasis can be present, however, in the absence of lymph node enlargement in patients with known or suspected lung cancer or other malignancy. Conversely, enlarged lymph nodes may just be post inflammatory or hyperplastic, especially in a patient without cancer risk factors. Very large lymph nodes (short axis >2 cm) in the middle mediastinum, including the subcarinal region, often reflect metastatic primary lung carcinoma, metastatic extrapulmonary carcinoma,† lymphoma, tuberculosis, fungal disease (e.g., histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis), or sarcoidosis. A careful review of the chest CT is always warranted to avoid confusion with a bronchogenic cyst,‡ a dilated azygos vein, esophageal varices, or a hiatal hernia.

This patient does not have a high pretest probability for sarcoidosis or another granulomatous disorder. In sarcoidosis, lymph node enlargement is seen in more than 80% to 95% of cases but predominates in the right paratracheal, aorto-pulmonary window, and hilar regions. CT scans show enlarged subcarinal lymph nodes in approximately 65% of patients.2

Although enlargement of lymph nodes in a single station can be seen in patients with Hodgkin’s disease, this most often occurs in the anterior mediastinum. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, on the other hand, may show involvement of only one node group in 40% of cases, most commonly involving the superior mediastinum. Another lymphoproliferative disorder, the hyaline vascular type of Castleman’s disease, is often asymptomatic, presents as a hilar or localized mediastinal mass in any mediastinal compartment, and could be responsible for this patient’s large subcarinal lymph node.2 The lack of multiple enlarged lymph nodes, constitutional symptoms, and normal laboratory markers makes rare lymphoproliferative disorders or leukemia less likely to explain this patient’s isolated subcarinal lymphadenopathy.

Comorbidities

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is reportedly associated with an increased complication rate after bronchoscopy compared with that seen in patients with normal lung function. Concern for bronchospasm is increased, but premedication with inhaled short-acting agonists is not routinely recommended.3

Support System

This patient lived alone and had very few acquaintances. Given that our main differential diagnoses were cancer and sarcoidosis, we wondered whether he might eventually benefit from participation in support groups. For people with sarcoidosis, many of these groups are available online, and they may become necessary when physical and emotional problems associated with this disease arise. In self-help groups, patients might better cope with problems and concerns related to their disease and feelings of isolation.4 Similarly, for cancer, support groups focus on behavioral issues and symptoms, or on the expression of emotions. Most of these support programs are structured to ensure delivery of information and to provide emotional and social support, stress management strategies based on cognitive-behavioral approaches, and relaxation techniques. Group therapy helps patients gain emotional support from others with similar experiences and learn to use these experiences to reduce their fear of dying and uncertainty.5

Patient Preferences and Expectations

Our patient was anxious about his potential diagnosis and had many questions regarding his health. In such circumstances, effective communication skills improve a patient’s understanding of the condition and promote adherence to potential treatment regimens. Having good communication skills helps health care providers use time efficiently, avoid burnout, and enhance feelings of professional fulfillment. Blocking,* lecturing, depending on a routine, collusion,† coercion, and premature reassurance are usually ill advised. One well-recognized and effective communication skill is the “ask-tell-ask technique,” which is based on the notion that providing patient education requires knowing what the patient already knows and building on that knowledge. Of course, building a relationship with a patient requires that the physician listen to the patient, understand and empathize with his perspectives, show compassion, and respect the patient’s agenda, even if it is not quite in line at all times with the way the physician might want to do things.6

Procedural Strategies

Indications

In general, proposed indications for endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA) include nondiagnostic conventional TBNA, staging of the radiologically normal mediastinum in case of suspected or confirmed lung cancer, mediastinal restaging after induction chemotherapy, and, more commonly, diagnosis of mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy.7 In patients with a history of cancer, such as ours, the diagnosis of new mediastinal adenopathy suggests recurrence of malignancy; therefore this diagnosis needs to be excluded or confirmed. Because not all cases of PET-positive mediastinal adenopathy are due to cancer recurrence, lymph node sampling is usually warranted. In this patient with a newly discovered large subcarinal lymph node, a tissue diagnosis was going to be obtained using EBUS-guided TBNA with the patient under general anesthesia.

Expected Results

1. In patients with previous malignancy and PET-positive lymph nodes, EBUS-TBNA has a yield greater than 90%. In one study, 73 lymph nodes from 48 patients were sampled, with each patient undergoing mediastinoscopy or thoracoscopy immediately after needle aspiration for histologic confirmation. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy of EBUS-TBNA were 97.4%, 100%, 100%, 87.5%, and 97.7%, respectively.8 In another study, similarly high sensitivity, specificity, diagnostic accuracy, and NPV of EBUS-TBNA for the diagnosis of mediastinal and hilar lymph node metastasis were found (92.0%, 100%, 95.3%, and 90%, respectively). Tumors encountered included colorectal, head and neck, ovarian, breast, esophageal, hepatocellular, prostate, renal, and germ cell cancers and melanoma.9

2. For primary lung carcinoma, a meta-analysis of 11 studies with 1299 patients found that overall, EBUS-guided TBNA (using both radial and convex probes) had a pooled sensitivity of 93% and a pooled specificity of 100%. The subgroup of patients selected on the basis of CT- or PET-positive results had higher pooled sensitivity (94%) than the subgroup of patients not selected on the basis of CT or PET findings (76%).10

3. The diagnosis of lymphoma may be controversial, although the use of flow cytometry, molecular biology techniques, and immunohistochemistry on cell block preparations may provide enough information for definitive diagnosis. Results from EBUS-TBNA were compared with a reference standard of pathologic tissue diagnosis of lymphoma or a composite of greater than 6 months of clinical follow-up with radiographic imaging. Nodes studied were larger than 5 mm and had a standardized uptake value (SUV) max higher than 4. Sensitivity was 90.9%, specificity 100%, PPV 100%, and NPV 92.9%.11 In another study, EBUS-TBNA had a sensitivity of 76%, but 20% of patients required surgical biopsy to completely characterize lymphoma subtypes, resulting in overall sensitivity of 57% and specificity of 100%.12

4. For fungal or mycobacterial infection, no studies have specifically addressed the yield of EBUS-TBNA. For patients with tuberculosis, however, in endemic areas, conventional TBNA has sensitivity of 83%, specificity of 100%, PPV of 100%, NPV of 38%, and accuracy of 85%.13 Future studies are necessary to determine whether EBUS-TBNA offers similar or better results.

5. For sarcoidosis, several studies have reported yields ranging from 82% to 95% for EBUS-TBNA.14–17

Team Experience

A single-institution study suggested that the learning curve for EBUS-TBNA for thoracic surgeons requires 10 procedures to reach the high yields reported in controlled clinical trials.18 In reality, however, the actual number of any given procedure performed does not account for the different rates at which people learn. With regard to EBUS-TBNA, one study assessed the learning curves of five independent operators by retrospectively applying cusum analysis* to the first 100 cases of each19; over a wide range of time, EBUS-TBNA competence was attained and the pooled sensitivity of EBUS-TBNA under conscious (moderate) sedation was 67.4%—lower than the high (>90%) rates reported in clinical trials.19

The usefulness of EBUS-TBNA resides in its clinical significance, accuracy, and reproducibility, which are usually shown to be excellent among pathologists experienced with these types of samples. Pathologists with little experience must climb what appears to be a steep learning curve.20

Diagnostic Alternatives

1. Conventional TBNA: For cancer, the yield of conventional TBNA for large subcarinal lymph nodes is similar to that of EBUS-TBNA, but EBUS guidance increases the yield of TBNA in all other stations.21 In the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, the overall diagnostic accuracy of TBNA cytology is as high as 86.2%.22

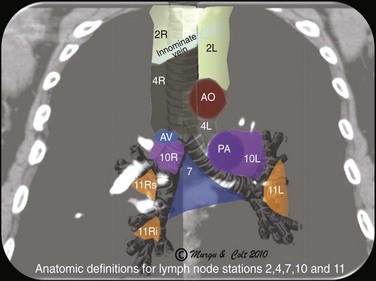

2. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-FNA: EUS alone is suitable for assessing lymph nodes in the posterior aspect of lymph node stations 4L, 5 (when significantly enlarged), and 7, and in the inferior mediastinum at stations 8 and 9 (Figure 19-2); data from lung cancer studies show that EUS-FNA and EBUS-TBNA have similarly high yields for diagnosing cancer involving lymph node station 7 (subcarinal).23 The overall diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity of EUS-FNA in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis were found to be 94% and 100%, respectively.24 A disadvantage of EUS-FNA is its lesser ability to access different hilar lymph nodes and nodes situated anterior and to the right of the trachea. These nodes are in fact those most commonly involved in sarcoidosis.

3. Mediastinoscopy: Mediastinoscopy provides systematic exploration and biopsy under visual guidance of stations 1, 2, 3, 4, and 7 (see Figure 19-2); mediastinoscopy is more invasive and has higher complication rates than are seen with needle aspiration techniques. With regard to suspected lung cancer, it was shown that up to 28% of patients with a high clinical suspicion of nodal disease had mediastinal nodal metastases confirmed by mediastinoscopy despite negative EBUS-TBNA25; therefore a negative EBUS-TBNA should be followed by mediastinoscopy when cancer is suspected. For sarcoidosis, mediastinoscopy is used as the gold standard for histologic confirmation.26 For patients with isolated mediastinal lymphadenopathy, the sensitivity of mediastinoscopy is 96%, and before the introduction of dedicated EBUS-TBNA, some experts recommended it as a procedure of choice to diagnose lesions in the axial (middle) mediastinum.27

Cost-Effectiveness

It is debatable whether EBUS-TBNA is more cost-effective than mediastinoscopy for evaluation of mediastinal lymphadenopathy in non–small cell lung cancer.28 In patients with a benign disease such as sarcoidosis, this issue has not been studied in a systematic fashion. Mediastinoscopy is usually considered the gold standard approach for undiagnosed mediastinal adenopathy, including sarcoidosis,29 and before the introduction of EBUS in clinical practice, one cost-benefit analysis of mediastinoscopy for patients with suspected stage I sarcoidosis (asymptomatic bilateral hilar adenopathy) showed that benefits of mediastinoscopy would be minimal and likely would be offset by the procedure’s morbidity and mortality.30

Techniques and Results

Anesthesia and Perioperative Care

We performed the procedure with the patient under general anesthesia, but many operators perform it with the patient under moderate (conscious) sedation. Many studies reporting a high yield for the procedure were conducted with patients under general anesthesia.28

Instrumentation

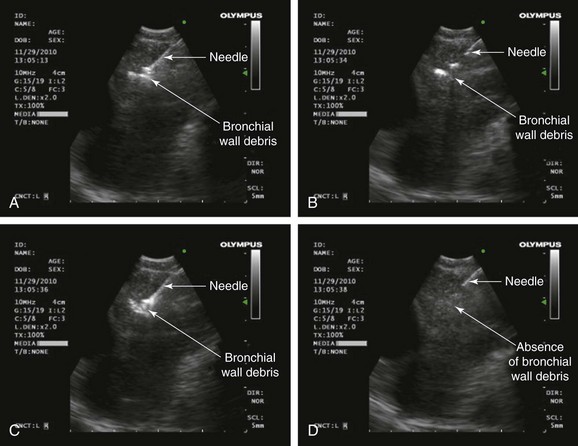

A dedicated EBUS bronchoscope, which offers direct real-time ultrasound imaging with a curved linear array transducer, was used. The frequency was set to 10 MHz. The associated ultrasound processor has adjustable gain and depth to optimize image quality, along with Doppler capabilities to distinguish vascular structures such as the heart and the inferior pulmonary veins; this is useful in sampling the subcarinal node. The 22 gauge acrogenic needle with an inner stylet allows for dislodgment of bronchial wall debris from the needle. This theoretically enhances the adequacy of the specimen (Figure 19-3). The needle guide system locks to the scope, and precise needle projection up to 4 cm is possible.

Anatomic Dangers and Other Risks

Concern has arisen regarding mediastinal abscess after EBUS-TBNA.31 In addition, pericarditis may occur in cases of inadvertent contamination of the pericardial space.32 With full-needle extension, the needle tip can be difficult to visualize, because small changes in the ultrasound angle can cause the needle tip to be out of plane with the ultrasound wave (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video IV.19.1![]() ). As a result, the pericardium (or vascular structures) may be violated but not visualized.32

). As a result, the pericardium (or vascular structures) may be violated but not visualized.32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree