This article is in Memoriam of Dr. Bernard D. Kosowsky who passed away in November 2015 at the age of 78 while riding his bicycle to work. Dr. Kosowsky was a student of such monumental figures as Drs Paul Zoll, Anthony Damato, W. Proctor Harvey, and Bernard Lown. He is credited for many discoveries in modern cardiac electrophysiology. Most importantly, Dr. Kosowsky was a mogul of Clinical Cardiology and bedside teaching at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center of Boston. His clinical lessons were passed on to many generations of young physicians.

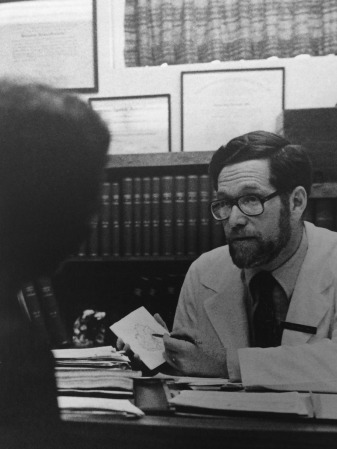

The sudden and unexpected death of Dr. Bernard Kosowsky ( Figures 1 to 3 ) at the age of 78 on November 19, 2015, brought an abrupt end to an illustrious career dedicated to clinical cardiology, expert patient care, and the teaching of many generations of young physicians.

Aware of mortality as we are, as fellow physicians and cardiologists, we somehow thought that he would always be there with us, as a monumental and even immortal figure who combined an unyielding demand for excellence with an understanding and unassuming nature, always focused on searching out the truth in complex medical situations. Dr. Kosowsky passionately taught generations of students the intricacies of diagnosis and decision making in our field. Will they be up to carrying on that tradition, or as some have asked since that day last November, have we seen the “Last of the Mohigans” in clinical cardiology?

Bernard Kosowsky was born in the Bronx, New York, on May 30, 1937. He was raised there by a loving Orthodox Jewish family who lived in humble circumstances. He was a superb student at the Columbia University and graduated from the Harvard Medical School in 1962 as the first student there to remain absolutely observant to the traditions of Orthodox Judaism. He was able to sustain the demands of that observance despite the rigors of the Harvard Medical School curriculum.

In his training, he was exposed to the pioneering efforts in transcutaneous pacing and alternating current defibrillation by the prodigious innovator, Dr. Paul Zoll. By pure serendipity, he landed a residency position in the first of its kind electrophysiology (EP) laboratory led by Dr. Anthony Damato at the Staten Island Public Health Service Hospital on Staten Island (1962 to 1964). During those amazing years, a group of young enthusiasts, who would each later go on to populate the entire world of cardiac EP, laid the groundwork for our understanding of the basics of the cardiac conduction system. This was the birth of what we now call clinical EP.

The researchers in the Damato laboratory studied many things: from the effect of medications and pacing on cardiac conduction to exploratory work on multisite pacing—the forerunner of today’s biventricular stimulation. In many of these discoveries, they were 30 to 40 years ahead of their time. Among the revolutionary achievements of Dr. Kosowsky and his Damato colleagues were the first-ever recordings of the His bundle potential in dogs and later in human volunteers. These discoveries have rightly been included in the reference book, “The Top Ten Clinical Advances in Cardiovascular-Pulmonary Medicine and Surgery Between 1945 and 1975: How They Came About.”

Bernard Kosowsky received credit for several of these discoveries, including His bundle pacing, the induction of atrial fibrillation by rapid atrial pacing, the termination of atrial flutter by burst pacing, to name but a few. He was a young but very prolific member of this incredible group that is rightly remembered as the founders of the modern School of Cardiac Electrophysiology. But he was then and remained throughout his life, modest about it all, recalling, “I was lucky to have been there.”

Following this amazing research experience on Staten Island, Bernard Kosowsky became a fellow and protégée of the legendary W. Proctor Harvey at Georgetown, under whose influence and tutelage he became an expert in clinical bedside cardiology and, specifically, the cardiac examination, which he defended through his life thereafter as a sensitive, specific, and inexpensive alternative to costly testing.

He strove to perfect the education in such skills to multiple generations of students, residents, and fellows. And, he remained a lifelong admirer of Dr. Harvey, who reciprocated in warm terms his admiration for his very talented protégée.

After completion of the Georgetown fellowship, Dr. Kosowsky arrived in Boston, where he studied under another legendary, albeit controversial, giant in Cardiology, Dr. Bernard Lown of Harvard. Dr. Lown’s influence was perhaps most noticeable in the conservatism of Dr. Kosowsky’s lifelong approach to clinical cardiology, and the maxim “first, do no harm.” However, many of the seminal reports that came from Lown’s laboratory in those years bore the imprint of his young fellow, Bernard Kosowsky.

On the completion of his training and research at the Brigham with Lown in 1971, Dr. Kosowsky headed to St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, where he rejuvenated and led the Division of Cardiology. St. Elizabeth’s was a very clinically oriented hospital, but nevertheless, Dr. Kosowsky’s inquisitive mind combined with his bedside acumen, and several new discoveries “just happened” (as he modestly recalled later), often as the result of “reading multiple ECGs,” poring over them with his residents and fellows, like long, rabbinical deliberations over some obscure passages of the Torah.

During these years, Bernard was the first to observe and understand the essence of phase IY AV block and multilevel block, using the simplest of tools. It is worth remembering that his favorite physician was Karel Frederik Wenckebach, who described second-degree type 1 AV block using only the carotid pulse and heart sounds, before the invention of the electrocardiogram!

Unfortunately, Dr. Kosowsky did not receive credit for the first description and understanding of the mechanism of the concealed bypass tract in AV conduction. We believe, based on the available evidence, that he was actually the first to identify the mechanism of that concealed conduction observing the response to ventricular overdrive pacing recorded on a simple electrocardiograph. He referred this first “concealed bypass tract” patient to a well-equipped EP laboratory capable of confirming his “leap of faith” diagnosis but did not receive authorship credit in the subsequent publication. This led to some disillusionment with academic medicine and its publication mores but not with research and discovery itself.

In fact, Bernard Kosowsky can be credited with bringing to St. Elizabeth’s a future leader in angiogenesis and stem cell research, Dr. Jeffrey Isner, showing incredible foresight for such a seemingly strictly bedside clinician.

Throughout his long life in Cardiology, Bernard Kosowsky was regarded by us as the “king of the rhythms and of the ECGs,” the ultimate judge in the most complex cases. He lectured frequently, presenting a series of complex rhythms that he had collected over nearly 50 years. His quiz on these “unknowns” was prized by the fellows, but scary. The “passing rate” was low, but every correct answer was immensely gratifying. His method was to remain silent while you struggled to interpret the complex rhythm, then deconstruct your often incorrect diagnosis, then launch an elegant explanation in defense of his own interpretation. Only with many such experiences did we come to understand that he did not expect perfection of interpretation but was trying to teach us how to think about the rhythm and its fundamental physiology. It was good that he was ultimately nonjudgmental since even EP attending did not get many of these complex tracing right! He was a great teacher and understood very well the dynamic nature of learning.

In his later years, Bernard Kosowsky remained a devoted physician to his patients and a tireless teacher to numerous medical students and young physicians. That bedside cardiology and clinical diagnosis remain hallmarks of the educational program at St. Elizabeth’s is a result of his relentless efforts and his famous teaching rounds. CCU and ward rounds were frequently long and detailed, with an incredible attention to detail, anything that would give a clue to the correct diagnosis or be important to ideal patient care. There is an anecdote, well known within the St. Elizabeth’s family, that 1 day his teaching rounds were so long that they persuaded his own son, then a medical student, to seek a field of medicine other than cardiology!

Many simple bedside “tricks of the trade” were taught to his students. One of them is particularly interesting, and one we have adopted now for many years: how does one avoid discomforting the patient when asking the patient to hold breath? An attentive doctor should hold his/her own breath when asking the patient to do the same—one’s own breathlessness will be the clue to allow breathing again. Bernard’s teaching on this is also an example of his extraordinary kindness to the sick, in the tradition of the clinical giants in the history of medicine.

Dr. Kosowsky was tireless—many of us did not know his age. He continued to see patients in his practice and on the wards and to take call at age 78. He never showed tiredness in teaching. He remained until the end the final arbiter not only on all complex ECGs but also on the thorniest of clinical problems. He was always there among us, the ultimate conscience, whose only question was, “is it the right thing to do?” It is difficult to walk our corridors without the expectation of seeing him again.

Bernard Kosowsky died suddenly while riding his bicycle to work on a rainy day in November. Patients were still waiting for him to arrive in the clinic after he had already passed away. They refused to believe that he was gone.

He was a quiet and unassuming person and very private. We did not know a lot about his life outside medicine, only that he was very devoted to his wife Joyce, their 4 children, and 13 grandchildren. Only at his funeral did we learn of his legendary role in the Jewish community of Boston, highlighted by his leadership of the Maimonides School in Brookline for >3 decades.

Even many months after losing him, we still see the shadow of his slim figure in the hallways at our medical center. The clinical teaching of Bernard Kosowsky has been passed like a baton to new generations of students, residents, and fellows—the tradition will live on.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree