14.2 DILATED CARDIOMYOPATHY

14.2.1 Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Dilated cardiomyopathy is not uncommon. Its prevalence in the general population is estimated to be 1 in 2500 individuals, although this may be an underestimation given the possibility of patients with asymptomatic cardiac dysfunction. Dilated cardiomyopathy arises from a variety of potential etiologies, but its unifying characteristic is myocardial injury that results in significant enlargement of the heart with subsequent ventricular dilatation. Table 14.1 lists several key examples of causes linked to various forms of dilated cardiomyopathy. However, most cases remain idiopathic despite extensive investigations. As with other forms of heart failure, reduced stroke volume from myocardial injury diminishes forward cardiac output, which in turn leads to pulmonary and venous congestion.

14.2.2 Clinical Characteristics and Evaluation

Patients with dilated cardiomyopathy typically present with classic symptoms of heart failure, including dyspnea on exertion, fatigue, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and orthopnea. Ascites and peripheral edema are also frequently present and may develop slowly over time. In addition to gathering information about symptoms, a complete history and physical examination should be obtained to look for potential etiologies. The EKG and chest X-ray are usually abnormal in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, although findings are nonspecific. The EKG may show atrial and ventricular enlargement, conduction defects, atrial and ventricular tachyarrhythmias, and diffuse repolarization changes in the ST and T wave segments. The chest X-ray classically shows an enlarged cardiac silhouette with various degrees of evidence for pulmonary congestion (e.g. interstitial and alveolar edema, pleural effusions).

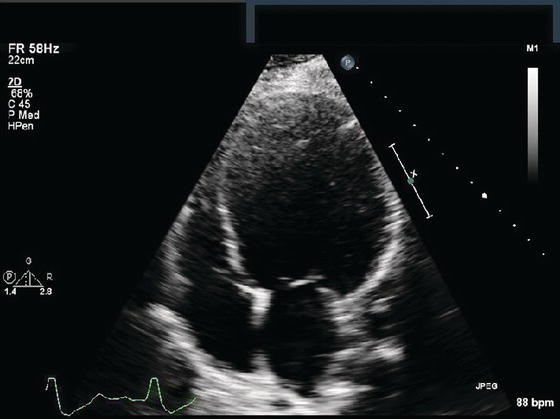

The echocardiogram is the most critical test in evaluating patients with suspected dilated cardiomyopathy. Findings from the echocardiogram show: (1) significant dilation of the left ventricle (LV) (although it can also involve the right ventricle [RV] and atrial chambers as well); (2) minimal or decreased wall thickness of the LV ventricle; and (3) markedly reduced systolic contraction of the LV as evidenced by a poor ejection fraction (EF) (Figure 14.1). Abnormalities in diastolic function as well as mitral and tricuspid regurgitation that can be detected by Doppler may also exist. Similar findings of LV dilation and systolic dysfunction are often noted on other cardiac imaging studies, such as nuclear scintigraphy and MUGA, cardiac MRI, and cardiac CT. Although these tests may provide additional information (e.g. extent of inflammatory or infiltrative processes), their use is typically restricted to specific settings. Cardiac catheterization with coronary angiography, on the other hand, is frequently performed to definitively rule out concomitant coronary artery disease. Right heart catheterization may help guide treatment goals by measuring intracardiac pressures, like the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, but biopsy of the right ventricle is rarely used as it is unusual for biopsy to change acute or chronic management plans.

Table 14.1 Key Examples of Causes Linked to Dilated Cardiomyopathy.

| Etiologies of dilated cardiomyopathy |

| Idiopathic Infectious Coxsackievirus EBV HIV Lyme Disease Medications Chemotherapeutic agents (doxorubicin, daunorubicin, cyclophosphamide) Antiretroviral agents Toxins Ethanol Lead Amphetamines Cocaine Carbon monoxide Metabolic disorders Hyperthyroidism Hypothyroidism Cushing’s disease Connective tissue disorders Systemic lupus erythematous Scleroderma Sarcoidosis Autoimmune myocarditis Others Peripartum cardiomyopathy Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy Radiation-induced cardiomyopathy Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy Hypocalcemia/hypophosphatemia Carnitine deficiencies |

Figure 14.1 Echocardiogram in the apical four chamber view of dilated cardiomyopathy. There is extensive dilatation of the LV with systolic dysfunction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree