Diffuse Idiopathic Pulmonary Neuroendocrine Cell Hyperplasia and Carcinoid Tumor

Fabio R. Tavora, M.D., Ph.D.

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

Marie-Christine Aubry, M.D.

Classification of Pulmonary Neuroendocrine Tumors

Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung are divided into four categories: typical carcinoid (TC), atypical carcinoid (AC), large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) (Chapter 80), and small cell carcinoma (SCLC) (Chapter 79). Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH) is considered a preinvasive lesion in the WHO classification of tumors of the lung.

The terminology of neuroendocrine tumors in the different organ systems varies, and there is some debate if the lung classification should also follow a classification of the gastrointestinal system, which separates the lesions into well, moderately, and poorly differentiated tumors, based on mitotic count and Ki-67 labeling index.1,2,3 However, the current WHO classification of tumors of the lung maintains the classification scheme of TC, AC, SCLC, and LCNEC.

Low- and intermediate-grade lesions (TC and AC) usually bear close resemblance to normal cells and show architecture and cytologic patterns of nonneoplastic cells and positivity for neurosecretory proteins. High-grade lesions (poorly differentiated carcinomas) are classified in the lung by the current WHO into SCLC and LCNEC. These tumors also express neuroendocrine markers, albeit less intensely, and also show reminiscence of neuroendocrine morphology.

Regardless of the classification used in the various organs, prognostic stratification is clinically relevant and reproducible among pathologists. Some evidence suggests that TC and AC, although variably aggressive, are genetically different from the high-grade lesions, which are uniformly aggressive.2,4,5 In the lung, SCLC exhibits marked sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy, whereas lower-grade lesions are unresponsive to these regimens.6

Carcinoid Tumors

Incidence

TC and AC tumors are rare and account for ˜1% to 2% of all lung carcinomas.7,8,9 The estimated incidence of carcinoid tumors ranges from 0.1 per 100,000 to 1.5 per 100,000, with 70% to 90% being TC.9 About 30% of carcinoid tumors in the body occur in the lung, second only to the tubular gastrointestinal system.10

Clinical and Radiologic Features

Carcinoid tumors occur in patients younger than high-grade lesions (mean age for carcinoid 45 to 50 years) with no predilection for sex or smoking history.1 Carcinoid tumors are the most common lung tumor seen in children. Carcinoid tumors can occur in the setting of familial syndromes, especially MEN1. Association with carcinoid syndrome is rare in lung tumors, occurring in <2% of the lesions.11 Cushing syndrome occurs more commonly, in up to 4% of patients, typically with peripheral TC. Other rare endocrine syndromes reported with carcinoid tumors include acromegaly and elevated parathyroid hormone.

Approximately 75% of carcinoid tumors are central in location, growing along the tracheobronchial tree, with invasion into the adjacent lung parenchyma or with an endoluminal growth. Therefore, patients often present with symptoms of obstruction including dyspnea, productive cough, wheezing, hemoptysis, and recurrent pneumonia. Peripheral tumors are usually discovered incidentally.

Radiologically, central carcinoid tumors present with atelectasis or obstructive pneumonia. Peripheral carcinoid tumors are well circumscribed with demarcated, rounded contours. Uptake on positron emission tomography (PET) tends to be lower in carcinoid tumors compared to other malignant carcinomas of the lung and usually lower in TC compared to AC. Octreotide imaging is often weak in pulmonary carcinoid tumors, compared to abdominal carcinoid tumors, because many do not have somatostatin receptors.

Gross Pathologic Findings

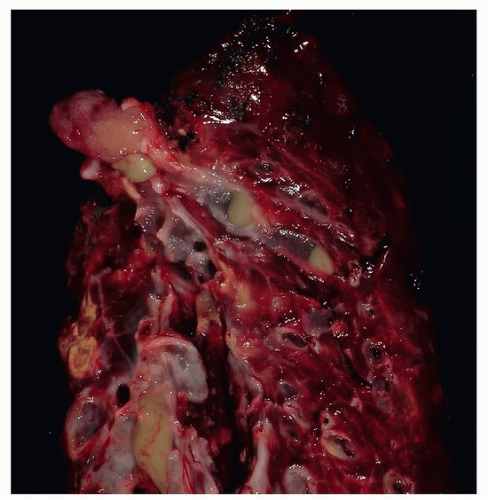

Grossly, these lesions are usually tan colored, well circumscribed, and round and may be pedunculated measuring a few centimeters.12 Central tumors with endoluminal obstruction are commonly associated with obstructive pneumonia. Localized bronchiectasis may also be seen (Fig. 81.1).

Histologic Features

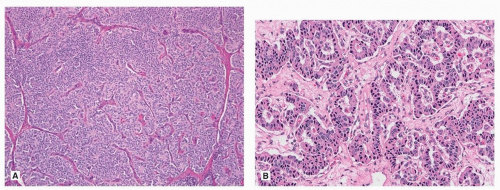

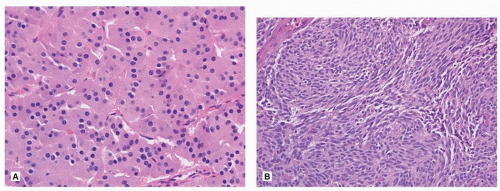

The overall morphology of TC and AC is similar to low- and intermediate-grade neuroendocrine tumors of other organs. The two most common growth patterns are organoid and trabecular (Fig. 81.2), but a heterogeneous mix of growth patterns can be easily seen in most lesions, with papillary formations, spindle cell change, and pseudoglandular growth among the most common (Fig. 81.2). While the tumor cells are usually bland, of small to intermediate size, scattered larger cells with striking pleomorphism is sometimes seen. These changes do not alter the diagnosis to AC category, although AC may show more prominent nucleoli and nuclear pleomorphism. The cell morphology in carcinoid tumors can be quite variable and may cause diagnostic challenges. Indeed, carcinoid tumor cells may have predominantly clear cytoplasm as seen in PEComa (Chapter 71) or metastasis from renal cell carcinoma, or abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm reminiscent of an oncocytoma (Fig. 81.3). Carcinoid tumors may have a prominent spindle cell morphology, typically in peripheral lesions (Fig. 81.3). Stromal hyalinization including bone formation (Fig. 81.4), mucinous background (Fig. 81.4), and amyloid has also been described.

FIGURE 81.3 ▲ Typical carcinoid. A. Cells contain abundant granular cytoplasm with oncocytic features. B. Spindle cell morphology usually seen in peripheral carcinoid tumor. |

The morphologic distinction between the TC and AC is based on only two features: mitotic count and necrosis.13,14 According to the current WHO classification, TC should measure more than 0.5 cm in size, contain < 2 mitoses per 2 mm2 (˜10 high-powered fields), and lack necrosis. ACs have 2 to 10 mitoses per 2 mm2 and/or foci of necrosis (Fig. 81.5). The necrosis is usually punctuate and focal in the tumor. Because of the importance of mitotic count to distinguish these two lesions, the WHO recommends that mitoses should be counted in the areas of highest activity, but if the cutoff of 2 or 10 is neared, at least three sets of 2 mm2 should be counted and the mean used for determining the mitotic rate, rather than the single highest rate. Furthermore, distinguishing typical from AC tumor may not be possible on a small biopsy specimen due to sampling.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree