Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

• Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) encompasses a heterogeneous group of pulmonary and nonpulmonary disorders characterized by widespread intra-alveolar bleeding.

• DAH is a medical emergency that can result in acute respiratory failure and death.

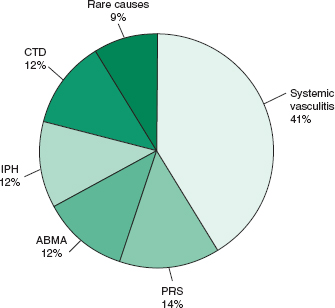

• The exact incidence and prevalence of DAH are unknown owing to the variety of underlying etiologies but the most common cause of DAH appears to be systemic vasculitis, in particular granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) (Fig. 19-1).1,2

• The pathogenesis of DAH is thought to be secondary to direct effects of autoantibodies on the alveolar capillary endothelium.

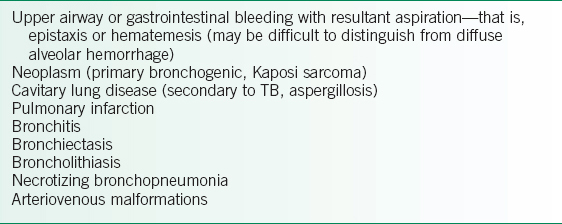

• Differentiation from localized etiologies (Table 19-1) of pulmonary hemorrhage is difficult to ascertain on history and physical examination alone; diagnostic procedures such as CXR and fiberoptic bronchoscopy are often needed.

FIGURE 19-1. Causes of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. ABMA, antibasement membrane antibody–mediated disease; CTD, connective tissue disease; IPH, idiopathic pulmonary hemorrhage; PRS, pulmonary renal syndromes. (Data from Travis WD, Colby TV, Lombard C, et al. A clinicopathologic study of 34 cases of diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage with lung biopsy confirmation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:1112–25.)

TABLE 19-1 CAUSES OF LOCALIZED PULMONARY HEMORRHAGE

DIAGNOSIS

• Appropriate diagnosis of DAH requires high clinical suspicion and a thorough history and physical examination.

• Rapid diagnosis of DAH is mandatory given the potential for excessive morbidity (renal failure, restrictive and obstructive lung disease) and mortality rates approaching 70–80% in untreated subsets of patients.

Clinical Presentation

• DAH should be suspected whenever a patient presents with hemoptysis, dyspnea, and a predisposing condition, such as an underlying connective tissue disorder, systemic vasculitis, or certain drug or occupational exposures.

• Hemoptysis, a presumed cardinal symptom of DAH, may be absent in up to one-third of cases despite pronounced and life-threatening alveolar hemorrhage.

• A detailed history of past and present medications (prescribed, over-the-counter, and recreational) and occupational exposures should be obtained.

Amiodarone, retinoic acid, sirolimus, penicillamine, and crack cocaine have all been implicated as causative agents of DAH.3

Amiodarone, retinoic acid, sirolimus, penicillamine, and crack cocaine have all been implicated as causative agents of DAH.3

Inhalation of trimellitic anhydride, a chemical found in paints, varnishes, and plastics, has also been reported as a cause of DAH.

Inhalation of trimellitic anhydride, a chemical found in paints, varnishes, and plastics, has also been reported as a cause of DAH.

• Physical examination findings are nonspecific and may include fever, hypoxemia, tachypnea, and diffuse crackles.

• Signs suggesting an underlying systemic disorder should be sought. These signs may include sinusitis, iritis, oral ulcers, arthritis, synovitis, palpable purpura, neuropathy, and cardiac murmurs.

Differential Diagnosis

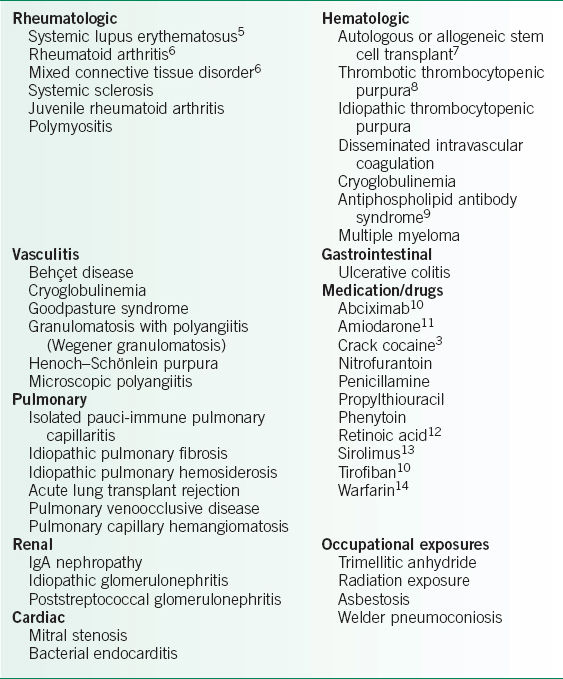

DAH is infrequently the initial presentation of an underlying systemic disorder (Table 19-2 and Fig. 19-1).1–14 Twenty percent of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and 5–10% of patients with Goodpasture syndrome present with DAH as the initial or sole manifestation. Therefore, emphasis should be placed on the rheumatologic, renal, pulmonary, and cardiac review of systems.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratories

• Laboratory evaluation is crucial for the diagnosis of DAH.

• Complete blood count

Anemia is commonly found, and repeated bouts of DAH may lead to an iron-deficiency anemia.

Anemia is commonly found, and repeated bouts of DAH may lead to an iron-deficiency anemia.

Thrombocytopenia or elevated coagulation parameters should raise the possibility of hemorrhage secondary to an acquired coagulopathy or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

Thrombocytopenia or elevated coagulation parameters should raise the possibility of hemorrhage secondary to an acquired coagulopathy or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

• Coagulation parameters

• Basic metabolic profile. If creatinine is abnormal, urine microscopy should be assessed for dysmorphic red blood cells or casts.

• Urinalysis

• Drug screen should be obtained on all patients to rule out cocaine use.3

• Serologic markers should also be obtained and their selection guided by the differential diagnosis.

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) (see Chapter 20)

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) (see Chapter 20)

Commonly found in GPA (Wegener granulomatosis), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), Churg–Strauss syndrome (CSS), and isolated pauci-immune capillaritis. ANCAs are occasionally seen in other disease states.15

Commonly found in GPA (Wegener granulomatosis), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), Churg–Strauss syndrome (CSS), and isolated pauci-immune capillaritis. ANCAs are occasionally seen in other disease states.15

Cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA) screens for the definitive antibody test, antiproteinase 3 (PR3), and likewise for perinuclear ANCA (p-ANCA) and antimyeloperoxidase (MPO). The level of c-ANCA may sometimes be useful in following disease activity but this is not consistently the case. In a literature review by Rao et al., the sensitivity of c-ANCA in active GPA was 91% versus 63% in inactive disease. The specificity was equivalent in both situations and approached 99%.16

Cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA) screens for the definitive antibody test, antiproteinase 3 (PR3), and likewise for perinuclear ANCA (p-ANCA) and antimyeloperoxidase (MPO). The level of c-ANCA may sometimes be useful in following disease activity but this is not consistently the case. In a literature review by Rao et al., the sensitivity of c-ANCA in active GPA was 91% versus 63% in inactive disease. The specificity was equivalent in both situations and approached 99%.16

p-ANCA, antibodies directed against MPO, is less specific and may be associated with many clinical syndromes. p-ANCA is found in 80% of patients with MPA. p-ANCA has also been identified in 15–20% of patients with GPA and up to 20–30% of patients with Goodpasture syndrome.

p-ANCA, antibodies directed against MPO, is less specific and may be associated with many clinical syndromes. p-ANCA is found in 80% of patients with MPA. p-ANCA has also been identified in 15–20% of patients with GPA and up to 20–30% of patients with Goodpasture syndrome.

Antiglomerular basement membrane (Anti-GBM) antibodies

Antiglomerular basement membrane (Anti-GBM) antibodies

Diagnostic for Goodpasture syndrome, characterized by antibodies (predominantly IgG) directed against the noncollagenous domain of type IV collagen, alpha 3.17

Diagnostic for Goodpasture syndrome, characterized by antibodies (predominantly IgG) directed against the noncollagenous domain of type IV collagen, alpha 3.17

The sensitivity and specificity of anti-GBM approaches 98%. Two percent to 3% of patients with renal biopsy-proven Goodpasture syndrome may have negative serum anti-GBM, making renal (and not lung) biopsy the gold standard for diagnosis.17,18

The sensitivity and specificity of anti-GBM approaches 98%. Two percent to 3% of patients with renal biopsy-proven Goodpasture syndrome may have negative serum anti-GBM, making renal (and not lung) biopsy the gold standard for diagnosis.17,18

Other serologic markers help to assess for SLE.

Other serologic markers help to assess for SLE.

Antinuclear antibody (ANA)

Antinuclear antibody (ANA)

Antidouble-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA)

Antidouble-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA)

Complement levels (C3 and C4)

Complement levels (C3 and C4)

TABLE 19-2 CAUSES OF DIFFUSE ALVEOLAR HEMORRHAGE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree