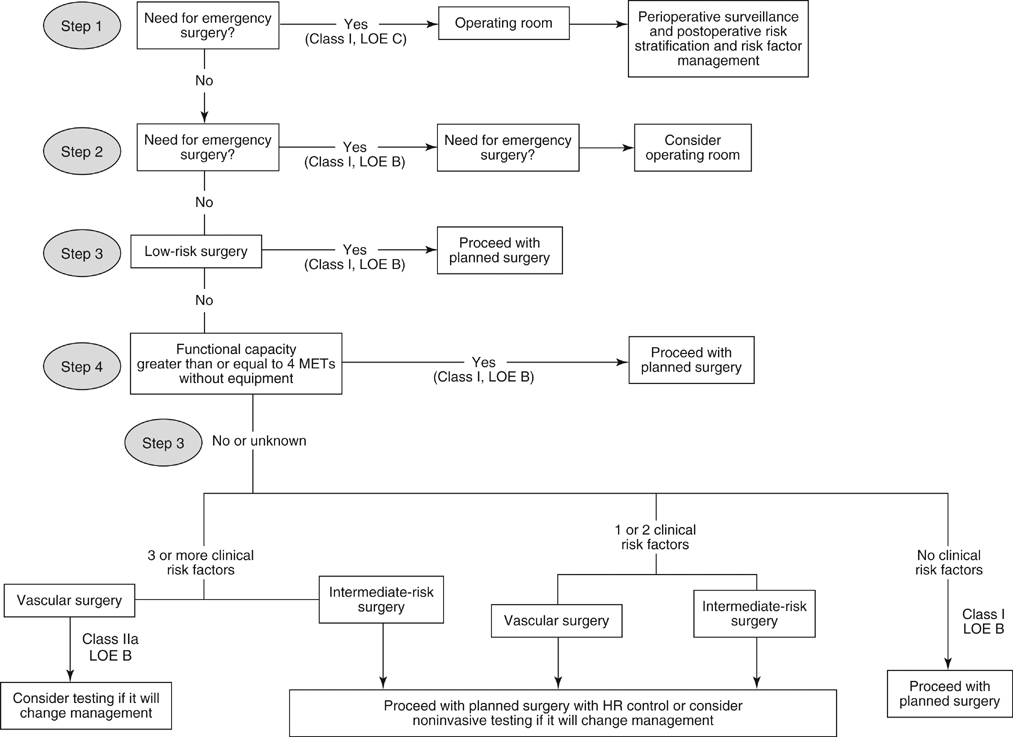

It is prudent to take a systematic approach to cardiac risk assessment in any patient with AAA or AIOD and a suspicion of coronary artery disease. The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association produced updated guidelines in 2007 for perioperative cardiac evaluation and care before noncardiac operative procedures. A general strategy for preoperative cardiac risk assessment is shown in Figure 1. Optimally, the strategy should be applied in the outpatient setting and should be used for elective operations.

Coronary Artery Disease in Patients with Aortoiliac Occlusive Disease and Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Preoperative Cardiac Risk Assessment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree