Chapter 12 Congenital Pulmonary Valve Regurgitation

William Osler1 described pulmonary regurgitation in The Principles and Practice of Medicine (1892): “This rare affection is occasionally due to a congenital malformation, particularly fusion of the two segments. … The condition is extremely rare and of little practical significance.” The distinctive diastolic murmur of low-pressure pulmonary regurgitation was characterized in 19102; and in 1936, isolated congenital pulmonary valve regurgitation was reported with a review of the literature.3 Maude Abbott’s4 necropsy study of 1000 cases of congenital heart disease included two examples of isolated congenital pulmonary valve regurgitation. In 1955, the first clinical diagnosis was made in an asymptomatic 24-year-old medical student.5

The morphology of the congenitally malformed valve is variable.6–8 One, two, or three cusps may undergo faulty development9,10; all three cusps may be rudimentary9; one cusp may be absent11 and the other two rudimentary8; very rarely, the pulmonary cusps are dysplastic12; or no valve tissue may be found at all—congenital absence of the pulmonary valve13,14—as reported by Chevers15 in 1846. The anomaly seldom occurs in isolation16–20 but instead coexists with Fallot’s tetralogy21 (see Chapter 18) and sporadically with other malformations.8,22,23

A bicuspid pulmonary valve is rare as an isolated anomaly and is only occasionally incompetent. A quadricuspid pulmonary valve typically occurs with truncus arteriosus (see Chapter 28) and only rarely in isolation.24,25 If the four cusps are equal, the quadricuspid valve functions normally; but with cuspal inequality or a supernumerary cusp, the valve is rendered incompetent, especially if the pulmonary artery pressure is elevated.24

This chapter is concerned with pulmonary valve regurgitation as an isolated congenital malformation. Regurgitation associated with pulmonary hypertension and a structurally normal pulmonary valve is dealt with in Chapter 14 on primary pulmonary hypertension.

Significance of the diagnosis of pulmonary valve regurgitation must take into account the relatively high incidence of trivial to mild pulmonary regurgitation identified incidentally with color flow imaging and Doppler interrogation in individuals whose hearts are structurally normal.26,27 Prevalence rate from birth to age 14 years is nil under 1 year of age, with a peak incidence rate of 42% between 6 and 11 years of age.26

The mature right ventricle is a low-pressure low-resistance pump that readily adapts to augmented volume, although the degree and duration of regurgitant flow are important determinants of this response.7 The physiologic consequences of pulmonary regurgitation are especially dramatic in utero because systemic pressure in the pulmonary trunk augments regurgitant flow, more so with agenesis of the fetal ductus.9,19 Acquired elevation of pulmonary arterial pressure in adults with bronchopulmonary disease or left ventricular failure is analogous but less dramatic.28

History

Isolated congenital pulmonary valve regurgitation usually comes to light because of a murmur or because of a dilated pulmonary arterial trunk in a routine chest x-ray. The diagnosis tends to be delayed, however, because the murmur is not detected at birth9 and routine chest x-rays are seldom done before adulthood. Gender distribution is about equal.29

Clinical manifestations of isolated congenital pulmonary valve regurgitation fall into three categories. The first and largest category consists of asymptomatic children, adolescents, and young adults,6,29 who tolerate the anomaly through middle age30 and occasionally into the sixth or even eighth decade.31 Isolated congenital absence of the pulmonary valve has been reported at age 69 years32 and 73 years.18

The second and much smaller category consists of adults in whom right ventricular failure occurs after decades of stability.28,29 Severe pulmonary valve regurgitation per se can cause the right ventricle to fail,33 but moderate regurgitation produces little or no ill effect until the degree of regurgitant flow is increased by adult-acquired elevation in pulmonary artery pressure associated with bronchopulmonary disease33 or left ventricular failure.28 Infective endocarditis is a low-probability cause of increased regurgitation.

A third and rare category of congenital pulmonary valve regurgitation occurs in the fetus19 or neonate9,29 when elevated pulmonary arterial pressure augments the volume of regurgitant flow across a congenitally malformed or absent pulmonary valve.19,29In utero patency of the ductus is desirable because ductal agenesis increases resistance to right ventricular discharge and increases regurgitant flow. The converse is the case with ductal patency after birth, which adds to the burden of the right ventricle by allowing diastolic flow to proceed from the aorta through the ductus into the pulmonary artery and across the incompetent pulmonary valve into the right ventricle.17,19,29,34

Precordial movement and palpation

When pulmonary regurgitation is mild to moderate, the right ventricular impulse is gentle and is detected only in the subzyphoid area during held inspiration. Severe regurgitation that accompanies congenital absence of the pulmonary valve generates a hyperdynamic impulse at the left sternal border and subzyphoid area, in addition to an impulse in the second left intercostal space caused by systolic expansion of the dilated pulmonary trunk (see Figure 12-7).29,31

Auscultation

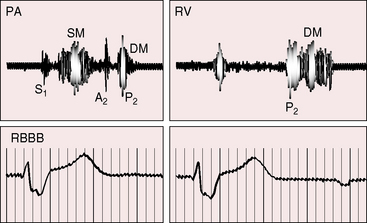

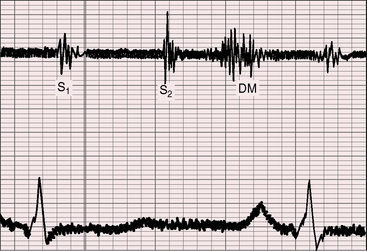

A normal first heart sound is occasionally followed by an ejection sound into the dilated pulmonary trunk. The pulmonary component of the second heart sound is absent when the leaflets are absent or rudimentary29,35 and soft when the cusps are present but defective, although audibility per se indicates the presence of valve tissue.36 The split tends to be wide because of a delay in the pulmonary component caused by increased capacitance of the pulmonary vascular bed and slow elastic recoil.36–38 The occasional occurrence of complete right bundle branch block also delays the pulmonary component of the second sound (Figure 12-1). Inspiration increases the degree of splitting unless the right ventricle has failed.36 Narrow splitting sometimes occurs because rapid right ventricular ejection coupled with brisk decline in the descending limb of the pulmonary artery pressure pulse cancels a potential delay in pulmonary valve closure.

The hallmark of congenital pulmonary valve regurgitation is the distinctive diastolic murmur. The murmur of low-pressure low-velocity regurgitant flow is maximal in the second or third left intercostal space, medium-pitched to low-pitched, crescendo-decrescendo, delayed in onset, and short in duration; and it ends well before the subsequent first heart sound (Figures 12-1 and 12-2).29,30,33,39 The murmur begins immediately after the right ventricular and pulmonary arterial pressure pulses diverge in early diastole, and is loudest at the timing of an early diastolic dip when the diastolic gradient is maximal (Figure 12-3A).33,39 If the pulmonary component of the second heart sound is soft or absent, a silent interval exists between the aortic component and the onset of the diastolic murmur (see Figure 12-2).39 Equilibration of pulmonary arterial and right ventricular pressures in latter diastole reduces or eliminates the regurgitant gradient and eliminates the murmur (Figures 12-3A, 12-4, and 12-5).39 The normally low diastolic pressure in the pulmonary trunk is responsible for the low rate of regurgitant flow and the correspondingly low to medium pitch of the murmur.39 Conversely, maximal instantaneous diastolic flow velocity in pulmonary hypertensive pulmonary regurgitation is maintained at about the same signal strength throughout diastole, which is appropriate for the high-frequency holodiastolic Graham Steell murmur (Figure 12-3B).40 The velocity of low-pressure pulmonary regurgitation peaks in early diastole and is followed by a gradual decline toward end-diastole. Accordingly, the low-frequency to medium-frequency diastolic murmur ends well before the subsequent first heart sound (see Figure 12-3A). Mild congenital pulmonary regurgitation permits the diastolic pressure in the pulmonary trunk to remain higher than the diastolic pressure in the right ventricle, so the low-frequency to medium-frequency murmur extends throughout diastole (see Figure 12-5).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree