Chapter 22 Congenital Coronary Arterial Fistula

Coronary arterial fistulas are the most frequent functionally significant congenital malformations of the coronary circulation; they comprise 14% of all congenital coronary artery anomalies and 0.2% to 0.4% of all congenital cardiac defects (see Chapter 32). The right and left coronary arteries arise from their appropriate aortic sinuses, but a fistulous branch of one or more than one drains into a cardiac chamber or into the pulmonary trunk, coronary sinus, vena cava, or a pulmonary vein.1 When the fistula drains into a right cardiac chamber or into the pulmonary trunk, it is arteriovenous, an appropriate term because the communication allows arterialized systemic blood—arterio—to mix with unoxygenated blood in the right side of the heart—venous. When the fistula drains into the left atrium or left ventricle, the appropriate term is coronary arterial rather than arteriovenous.

Congenital coronary arterial fistula was described by Krause2 in 1865 and confirmed by Abbott in 19083 and by Trevor in 1912.4 Approximately half of these fistulas arise from the right coronary artery, somewhat less from the left coronary artery, and only 5% from both coronary arteries.5 Even more rarely, all three coronary arteries are involved,6 or multiple fistulas arise from one coronary artery7 or from a single coronary artery.8 Isolated reports have appeared of fistulas from the conus artery to the right atrium,9 from the coronary sinus to the left ventricle,10 from the left circumflex to the coronary sinus11,12 or to the pulmonary artery,13 or from the microfistulae to the left ventricle.14 A significant minority of these fistulas are acquired (i.e., traumatic) because of intravascular, interventional, or surgical procedures.15–17 The contralateral coronary artery is absent in about 3% of congenital cases.

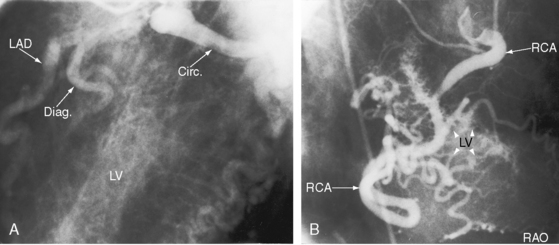

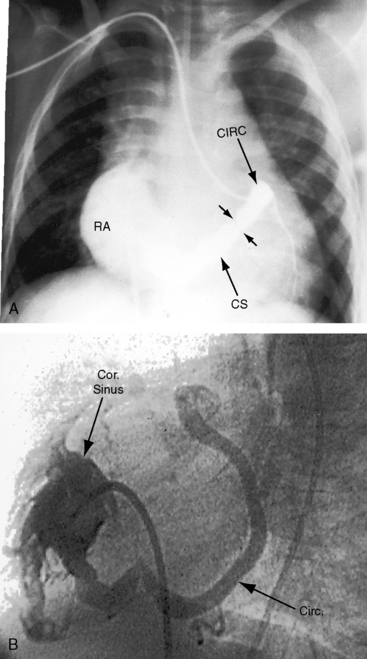

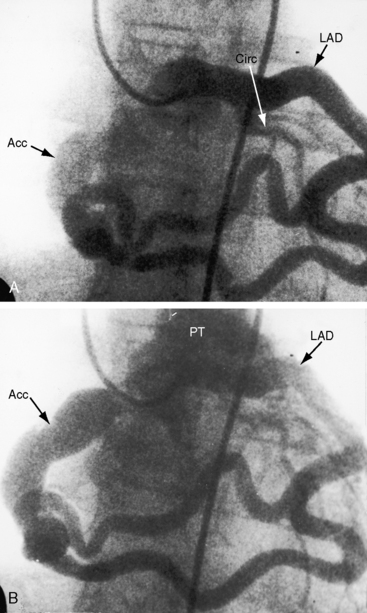

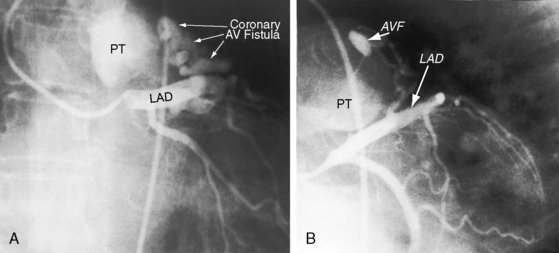

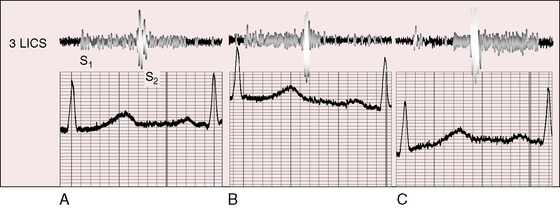

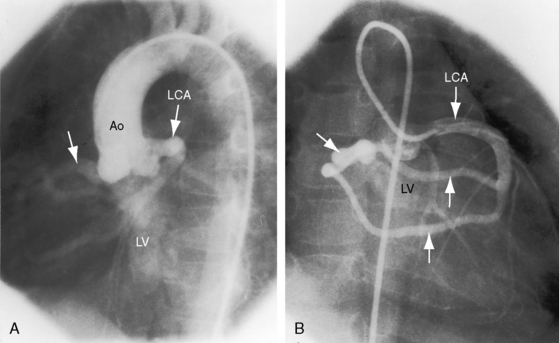

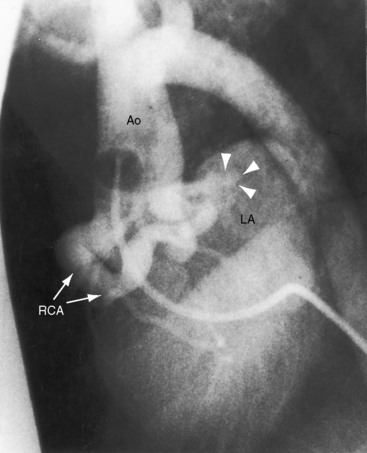

The drainage site of a coronary arterial fistula is more important than its site of origin and consists of a single vascular channel, multiple channels, or a maze of fine channels that form a diffuse network or plexus (spongy myocardium), a pattern especially likely when the left ventricle receives the fistula (see Figure 22-6B).14 More than 90% of congenital coronary arterial fistulas drain into the right side of the heart and are therefore arteriovenous. A substantial majority, in approximate order of frequency, enter the right ventricle (40%) or right atrium (25%) (Figure 22-1A); less commonly, the pulmonary trunk (15%; Figures 22-2 and 22-3) or coronary sinus (7%; Figure 22-1B)18; and rarely, the hepatic vein19 or superior vena cava.20–22 A dual right coronary artery has been accompanied by a fistulous communication.23 The coronary sinus that receives a fistula can be aneurysmal, especially if it receives fistulas from two coronary arteries (see Figure 22-7).5 A giant right coronary artery–to–superior vena caval fistula has been reported,24 as has an aneurysmal coronary artery fistula in which the left main coronary connected to the right atrium.25 Bilateral coronary arterial fistulas usually drain into the pulmonary trunk. The relatively few that do not communicate with the right side of the heart drain into the left atrium (5%; Figure 22-4), left ventricle (3%; Figures 22-5 and 22-6),26,27 pulmonary veins, or both ventricles. A coronary artery–to–left ventricular fistula is not the same as an aortic–to–left ventricular tunnel (see Chapter 6).27,28 Small coronary arterial fistulas without clinical evidence of their presence have been unexpectedly discovered during routine echocardiography (see Figure 22-18) and are incidental findings in 0.1% to 0.26 % of patients undergoing routine coronary angiography (see Figure 22-3B).29 In a series of 14,708 coronary arteriograms, 19 congenital coronary arterial fistulas were found; and in a series of 11,000 coronary angiograms, 13 fistulas were identified.30 These incidentally found fistulas are characterized by one or more small channels that originate from the left anterior descending coronary artery and form networks that communicate at sites in the pulmonary trunk (see Figure 22-3B).

The coronary artery that gives rise to the fistula is characteristically dilated, elongated, and tortuous (see Figure 22-2),31 and the coronaries distal to the fistula are of normal caliber (see Figure 22-3A). A fistulous coronary artery may contain saccular aneurysms that reach an astonishing size and may rupture (see previous).32,33

An estimated 1% to 2% of coronary arterial fistulas close spontaneously in infants, children, and adults.34,35 Occlusion of an atherosclerotic coronary artery proximal to the fistula was responsible for closure in a 44-year-old woman. Occasionally, calcification of the wall of the fistula and thrombi with embolization are seen.

The embryogenesis of coronary arterial fistulas is uncertain. Fistulas that enter the right ventricle have been related to persistence of primitive intramyocardial sinusoids36 or to the development of a rectiform vascular network in the distal branches of the involved coronary artery.18 Fistulas that enter the left ventricle are thought to result from direct flow through thebesian venous channels.37 Interestingly, the veins of Thebesius were cited as evidence of direct passage of blood from one side of the heart to the other before William Harvey discovered the circulation (see Chapter 32).

Of the six coronary anlagen in the embryo, three are in the developing aorta and three are in the developing pulmonary artery (see Chapter 21).38 These anlagen are normally involute, except for the two from the right and left aortic sinuses. The relatively high incidence of bilateral coronary arterial–to–pulmonary arterial fistulas is in accord with this observation. A coronary arterial–to–pulmonary artery fistula may result from persistence of one or more of the pulmonary arterial anlagen, hence the term accessory coronary artery, which is either a single large channel (see Figure 22-2), one or more smaller channels, multiple tortuous channels, or a plexiform arrangement.

The physiologic consequences of coronary arterial fistulas depend on the volume of blood flowing through them, the chamber or vascular bed into which they drain, and the myocardial ischemia that results from a coronary steal caused by low-resistance vascular channels. About 10% of blood from the aortic root normally enters the coronary circulation, but in the presence of a coronary arterial fistula, the volume is considerably larger. A fistula that drains into the right atrium, right ventricle, or coronary sinus constitutes a left-to-right shunt. If drainage is into the right ventricular outflow tract, pulmonary trunk (see Figures 22-2 and 22-3), left atrium (see Figure 22-6), or left ventricle (see Figures 22-4 and 22-5), the hemodynamic burden is borne by the left ventricle alone.26 A fistulous coronary artery receives blood during systole when its stoma is large.26,39 If the fistula drains into the inflow tract of the right ventricle, volume overload of the right ventricle coexists. If drainage is directly into the right atrium or indirectly through the coronary sinus (see Figure 22-1), volume overload of right ventricle exists in addition to overload of the left side of the heart.

Pulmonary-to-systemic flow ratios are typically small, even negligible, regardless of patient age. Shunts in excess of 2:1 are unusual, but an occasional neonate experiences congestive heart failure (see Figure 22-17) when an exceptionally large fistula drains into the left or right side of the heart.36,39

Myocardial ischemia is incurred when a coronary arterial fistula functions as a low-resistance pathway that constitutes a coronary steal.26 The coronary artery gives rise to the fistula and then assumes an important role because steal from a major branch of the left coronary artery is more significant than steal from a smaller right coronary artery. Acquired coronary artery stenosis distal to a congenital coronary arterial fistula aggravates the perfusion deficit because the fistula acts as a low-resistance alternative to the acquired obstruction.

History

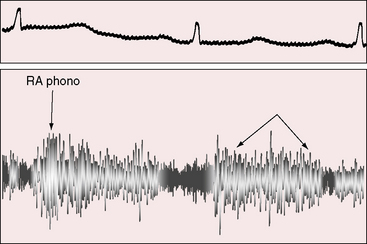

The initial suspicion of a congenital coronary arterial fistula in an asymptomatic child or young adult is likely to be a continuous murmur. A small acoustically silent coronary arterial fistula is usually discovered during routine echocardiography or coronary angiography (see previous). When a coronary arterial fistula drains into the low-pressure right or left atrium, the continuous murmur dates from birth because the pressure gradient responsible for the murmur is present in utero. Conversely, coronary arterial fistulas that drain into the right ventricle or pulmonary trunk do not generate continuous murmurs until after the neonatal fall in pulmonary vascular resistance. The continuous murmur is overlooked when it is soft and localized to an atypical site. An isolated diastolic murmur may be heard but misinterpreted. Coronary arterial fistulas are mistaken for patent ductus arteriosus (Figure 22-8), which occasionally coexists.40,41 A coronary arteriovenous fistula may present with angina,26,42 and occasionally with a pericardial effusion13 or infective endocarditis.22

The male:female ratio is about equal. Survival into adulthood is expected, but lifespan is not normal.18 Longevity has been reported in the sixth to ninth decade (see Figure 22-16),13,43 and the diagnosis has been made as late as the seventh to ninth decade.44 A 68-year-old professional athlete was undiagnosed until acquired coronary artery disease prompted coronary angiography, which disclosed bilateral coronary arterial fistulas.

Most patients, especially those less than 20 years of age, are asymptomatic when the coronary arterial fistula is first diagnosed.18 An uncommon, if not rare, exception is the infant with an exceptionally large fistula (see Figure 22-17).36,39 Symptoms and complications, in approximate order of frequency, include dyspnea, fatigue, myocardial ischemia,26 congestive heart failure, sudden death,45 infective endocarditis,22,46 and rupture.47 Obstruction of the superior vena cava has been caused by a large fistulous saccular aneurysm, one of which ruptured at age 82 years.48 Atrial fibrillation that accompanies drainage into the right or left atrium or coronary sinus heralds congestive heart failure (see Figure 22-16).

A coronary steal may be the cause of myocardial ischemia and angina pectoris (see previous), and ischemia has an undesirable effect on left ventricular function.26,49 Spontaneous closure of a coronary arterial fistula is uncommon but not rare (see previous).34,35