Chapter 5 Congenital Abnormalities of the Pericardium

Congenital absence of the pericardium was recognized by M. Realdus Columbus1 in 1559 and by Matthew Baille2 in 1793, but the anomaly was not clinically diagnosed in a chest x-ray until 1959.3 The pericardial abnormality varies from a localized defect to complete absence.4–6 The sternum, abdominal wall, pericardium, and part of the diaphragm arise from somatic mesoderm. Morphogenesis of congenital defects of the left pericardium has been attributed to premature atrophy of the left duct of Cuvier that results in deficient blood supply to the left pleuropericardial membrane.7,8

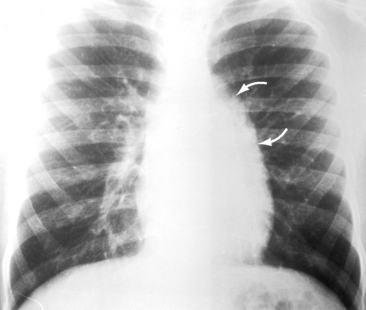

The necropsy incidence rate of congenital absence of the pericardium has been estimated at 1/14,000.9 About two thirds of cases are represented by partial absence of the left pericardium (Figure 5-1).9–11 Congenital absence of the right pericardium is rare (Figure 5-2).6,12 Approximately one third of congenital pericardial defects occur in conjunction with other congenital malformations, both cardiac (Figure 5-3) and noncardiac.4,13,14 A case in point is the Cantrell’s syndrome described in 195813 (also called the Cantrell-Heller-Ravitch syndrome) that consists of two major defects, ectopia cordis and epigastric omphalocele, and three lesser defects, cleft of the distal sternum and defects of the anterior diaphragm and diaphragmatic pericardium.13,15,16

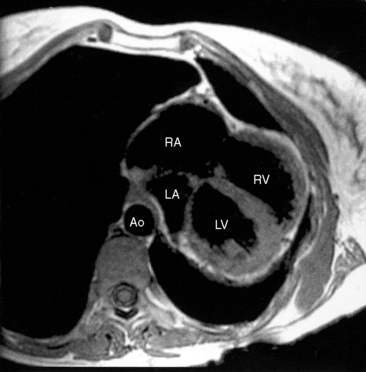

Figure 5-2 Magnetic resonance image with axial view from a 38-year-old woman with congenital complete absence of the pericardium and hypoplasia of the left lower lobe and the left pulmonary artery (see Figure 5-3). The strikingly mobile heart is displaced far into the left thoracic cavity. (LA/RA = left and right atrium; LV/RV = left and right ventricle; Ao = aorta.)

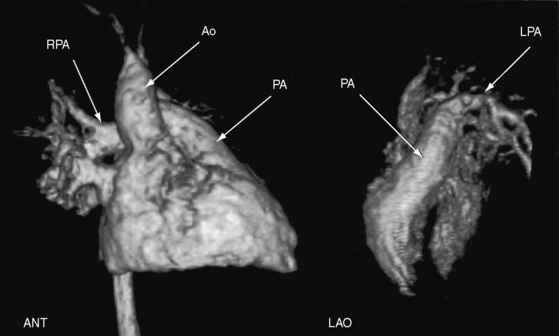

Figure 5-3 Three-dimensional reconstruction of gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography of the heart and great arteries from the 38-year-old woman with congenital complete absence of the pericardium with hypoplasia of the left lower lobe and left pulmonary artery (see Figure 5-2 for magnetic resonance image). The left anterior oblique view (LAO) discloses a hypoplastic left pulmonary artery (LPA). The anterior view (ANT) discloses a well-formed main pulmonary artery (PA) and a well-formed right pulmonary artery (RPA). (Ao = ascending aorta.)

The parietal pericardium exerts contact stress that contributes to ventricular diastolic pressure and limits acute dilation.17 The stress is greater on the relatively thin right ventricle and right atrium whose dimensions and pressures depend chiefly on pericardial constraint.17 Accordingly, congenital complete absence of the parietal pericardium is accompanied by alterations in systemic venous return18 and an increase in right ventricular size.17 Alternans of the right ventricular diastolic pressure has been reported during cardiac catheterization in a patient with congenital complete absence of the pericardium.19

History

Partial or complete absence of the pericardium usually comes to light because of an abnormality on the routine chest x-ray of an asymptomatic patient or in a chest x-ray taken as part of the cardiovascular evaluation of a symptomatic patient with coexisting cardiac defects.4 The most common symptom is chest pain that appears suddenly in a previously asymptomatic adult and that varies from mild and occasional to frequent, prolonged, and debilitating.4 The pain is stabbing; left-sided; brief, if not fleeting; unrelated to exertion but aggravated by position, especially the left lateral decubitus; awakens the patient from sleep; and is relieved with an upright position.6,20 The pain associated with partial absence of the left pericardium (see Figure 5-1) is attributed to herniation of the left atrial appendage through the pericardial defect. The pain associated with complete absence of the pericardium (see Figure 5-2) is believed to originate from torsion of the thoracic inlet.20 In light of evidence of transient compression of coronary arteries, myocardial ischemia is also a consideration.21,22

Familial congenital partial absence of the left pericardium has been reported.7 The male:female prevalence ratio is reportedly 3:1. Longevity is not affected by congenital partial absence of the pericardium20 but has not been established with congenital complete absence. However, one patient reportedly survived to the eighth decade.23

Physical appearance

Congenital partial absence of the left pericardium has been reported with abnormal facies and growth hormone deficiency24 and with VATER defects (V, vertebral defects; A, anal atresia; T, tracheo; E, esophageal fistula; R, radial atresia and renal dysplasia).25

Arterial pulse and jugular venous pulse

The arterial pulse is normal with congenital complete absence of the pericardium despite alternans of diastolic pressure.19 The jugular venous pulse is normal with congenital partial absence of the pericardium and is normal with congenital complete absence, despite the decrease in contact stress exerted on the right atrium and right ventricle.