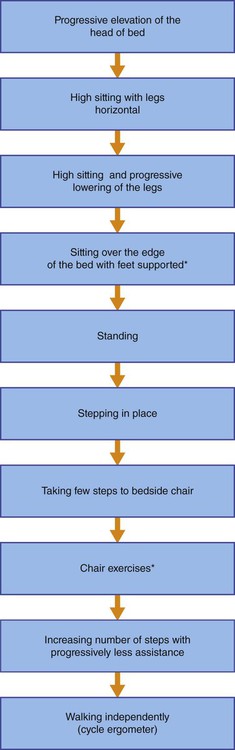

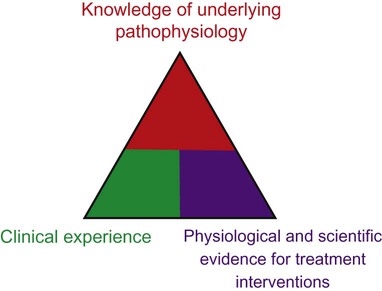

The thrust toward evidence-based practice in health care and the development of conceptual bases for practice have had major implications for cardiovascular and pulmonary physical therapy in the ICU.1–4 Superior knowledge of cardiovascular and pulmonary physiology, pathophysiology, pharmacology, multisystem dysfunction and its medical management, and ICU equipment and changing technology is essential. Clinical decision making in the ICU and rational management of patients is based on a tripod approach: knowledge of the underlying pathophysiology and basis for general care; knowledge of the physiological and scientific evidence for treatment interventions; and clinical reasoning and decision making in prioritizing treatments, prescribing their parameters, and performing serial evaluation to assess outcomes and further modify treatment (Figure 33-1). High-quality care is a function of these three areas of knowledge and expertise. Evidence-based practice and excellent problem-solving ability will optimize outcomes5 and maximize the benefit-to-risk ratio of cardiovascular and pulmonary physical therapy interventions. Effective clinical decision making and practice in the ICU demand specialized expertise and skill, including advanced, state-of-the-art knowledge in cardiovascular and pulmonary and multisystem physiology and pathophysiology and in medical, surgical, nursing, and pharmacological management (Box 33-1). Physical therapists in the ICU need to be first-rate diagnosticians and observers. Given the multitude of factors that contribute to impaired oxygen transport,6 the physical therapist needs to analyze these to define the patient’s specific oxygen transport deficits and problems. Optimizing oxygen delivery in the patient who is critically ill7 by exploiting noninvasive interventions is the priority. 1. Return the patient to his or her premorbid functional level or a higher level if possible 2. Reduce complications, morbidity, premature mortality, and length of ICU and overall hospital stay Many elements of the assessment of patients in the ICU are comparable to those for patients with acute conditions who are not critically ill but require respiratory support and mechanical ventilation (see Chapter 44). The primary difference is that for patients in the ICU the adequacy of the steps in the oxygen transport pathway are monitored closely, and the status and function of multiple organ systems are monitored in a serial (repeated at regular or judicious intervals) manner to observe trends over time so that treatment modifications can be titrated to the patient’s responses. Serial vital signs including pain and distress are recorded along with arousal and cognitive status, neuromuscular status, musculoskeletal status, and functional mobility. Assessment of functional mobility ranges from the smallest movement to walking (see Figure 33-2 and Box 33-4). Often it includes bed mobility, transfers to chair, and walking, which may require assistive devices. Related laboratory investigations are noted, including the electrocardiogram (ECG), radiographs, scans, blood work, blood sugar level, and fluid and electrolyte balance, and are followed closely to quickly detect improvement or deterioration so that treatment can be correspondingly modified. Mechanical ventilation and its modes and parameters are described in Chapter 44. The ventilator settings including the fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) are important indicators of changes in the patient’s status and therefore must be included in the assessment and recorded at each treatment. Similarly, changes in FIO2 are important outcomes and indicators of treatment response. This information is used collectively in clinical decision making before, during, and after weaning from mechanical ventilation. In patients who are medically stable, invasive mechanical ventilation is titrated judiciously to ensure that the patient is initiating breaths as much as possible, which facilitates weaning. Depending on the patient’s response to ventilation, however, sedation and neuromuscular blockade may be indicated. These interventions limit the patient’s capacity to cooperate fully with treatment. Breathing patterns imposed by the mode of mechanical ventilation influence venous return and aortic pressures8; thus mobilization needs to be prescribed accordingly. Furthermore, weaning patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and neuromuscular conditions is complicated by respiratory muscle weakness and fatigue (see Chapter 26), which may indicate respiratory muscle training or rest. Because of these challenges, weaning necessitates close cooperation and coordination within the team to maximize weaning success. As for patients who are not critically ill, the assessment data are evaluated, problems and diagnoses made, and interventions prescribed based on the patient’s needs and goals. Physical therapy has a prominent role in the management of patients who are on mechanical ventilation.9,10 With each treatment, the responses are reviewed and prescription parameters of the interventions are refined to progress the patient Hospitalization, particularly in the ICU, is associated with a considerable reduction in mobility (i.e., loss of exercise stimulus) and recumbency (i.e., loss of gravitational stimulus) (see Chapters 18 and 20).11–13 These two factors are essential for normal oxygen transport; thus their removal has dire consequences for the patient with or without cardiovascular and pulmonary dysfunction. In terms of a physiological hierarchy of treatment interventions (see Chapter 17), exploiting the physiological effects of acute mobilization, upright positioning, and their combination is the most physiologically justifiable primary intervention to maximize oxygen transport and prevent its impairment in patients who are critically ill. Recumbency is nonphysiological; it is a position in which, all too often, most patients are injudiciously confined. Changing the position of the body from erect to supine positions results in significant physiological changes that may jeopardize the patient’s already compromised or threatened oxygen transport system (Box 33-2) (see Chapter 20). Physical therapy interventions in the ICU (see Chapter 17 and Part III) are more specifically geared toward the status of each organ system, taking into consideration the pathophysiological basis for the patient’s signs and symptoms, the rationale for each intervention, and the physiological and scientific evidence supporting the effectiveness of the intervention.14 Physical therapy provides both prophylactic and therapeutic interventions for the patient in the ICU. Conservative, noninvasive measures constitute initial treatments of choice to avert or delay the need for additional invasive monitoring and treatment including supplemental oxygen, pharmacological agents, and the need for intubation and mechanical ventilation. The physical therapist aims to avoid, reduce, or postpone for as long as possible the need for respiratory support. Even if the patient is mechanically ventilated, maintaining some level of spontaneous breathing, no matter how minimal, is associated with improved oxygenation and outcomes.15 In addition, the physical therapist helps to prevent the multitude of side effects of restricted mobility and recumbency during bed rest. A summary of general information required before treatment of the patient in the ICU is presented in Box 33-3. This provides the basis for establishing a patient’s readiness to be mobilized and the progressive steps for doing so (Box 33-4 and Figure 33-2). Maximizing function refers to maximizing the capacity to participate in one’s life roles and associated activities. This necessitates promotion of optimal physiological functioning at an organ system level, as well as promoting maximal functioning of the patient as a whole. In critical care, primary goals related to function optimization are initially focused on cardiovascular and pulmonary function. With improvement in oxygen transport, increased attention is given to optimal functioning of the patient with respect to self-care, self-positioning, sitting up, and walking. General physical therapy goals related to function optimization are shown in Box 33-5. Outcomes can be tracked objectively by recording the length of time a patient sits over the edge of the bed, sits in a chair at bedside, stands, and walks. Also, the weight a patient lifts as well as the number of repetitions and sets he or she performs can be readily quantified.

Comprehensive Management of Individuals in the Intensive Care Unit

Specialized Expertise of the Intensive Care Unit Physical Therapist

Goals and General Basis of Management

Restricted Mobility and Recumbency

Specificity of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Physical Therapy

Maximizing Function

Comprehensive Management of Individuals in the Intensive Care Unit