Mental stress increases cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Although laboratory mental stress often causes less myocardial ischemia than exercise stress (ES), it is unclear whether mental stress is intrinsically different or differences are due to less hemodynamic stress with mental stress. We sought to evaluate the hemodynamic and ischemic response to intense realistic mental stress created by modern flight simulators and compare this response to that of exercise treadmill testing and conventional laboratory mental stress (CMS) testing in pilots with coronary disease. Sixteen airline pilots with angiographically documented coronary disease and documented myocardial ischemia during ES were studied using maximal treadmill ES, CMS, and aviation mental stress (AMS) testing. AMS testing was done in a sophisticated simulator using multiple system failures as stressors. Treadmill ES testing resulted in the highest heart rate, but AMS caused a higher blood pressure response than CMS. Maximal rate–pressure product was not significantly different between ES and AMS (25,646 vs 23,347, p = 0.08), although these were higher than CMS (16,336, p <0.0001). Despite similar hemodynamic stress induced by ES and AMS, AMS resulted in significantly less ST-segment depression and nuclear ischemia than ES. Differences in induction of ischemia by mental stress compared to ES do not appear to be due to the creation of less hemodynamic stress. In conclusion, even with equivalent hemodynamic stress, intense realistic mental stress induced by flight simulators results in significantly less myocardial ischemia than ES as measured by ST-segment depression and nuclear ischemia.

The purpose of this study was to compare myocardial ischemia caused by intense realistic workplace-related mental stress in a sophisticated flight simulator to that of conventional laboratory mental stress (CMS) testing and maximal treadmill exercise stress (ES) in pilots with known coronary artery disease. Mental stress-induced ischemia occurs less frequent than and does not correlate well with exercise-induced ischemia. CMS stimuli may be less intense than real-life stressful stimuli. Whether the lack of correlation between mental stress-induced and exercise-induced ischemia is due to the lack of realism and/or intensity in CMS testing is unknown.

Methods

Subjects were airline transport pilots who had lost their Federal Aviation Administration medical certificate because of coronary disease and were recruited with the assistance of the Federal Air Surgeon, Federal Aviation Administration, and Airline Pilots Association. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Christiana Care Health System with written informed consent. Approval was obtained from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to administer isotopes in the flight simulator. Pilots had aviation mental stress (AMS) testing, CMS testing, and treadmill ES testing carried out on sequential days, with AMS and ES testing performed using perfusion imaging with sestamibi. Perfusion imaging was not feasible during CMS because of excessive radiation exposure. Testing order was random per pilot. All tests were carried out at noon. Antianginal medications were discontinued ≥24 hours or 5 ½ lives before testing.

For ES the pilots fasted for ≥4 hours before exercising according to a standard Bruce protocol. For CMS the subjects were attached to a 12-lead electrocardiograph, blood pressure monitor, and a skin conductance monitor to assess degree of sympathetic arousal. After a 30-minute period of quiet relaxation, an investigator unknown to the subject approached and instructed the subject to speak for 5 minutes on an assigned topic, which involved a difficult interpersonal scenario, while the subject’s performance was observed, evaluated, and criticized by the laboratory staff. During this time the subject was intentionally frustrated and challenged. The end point was a significant amount of arousal, defined as an increase in systolic blood pressure or skin conductance of ≥25%. For AMS flight scenarios were carried out in a level C full-motion flight simulator at Flight Safety International, Greater Wilmington Airport, Wilmington, Delaware. This simulator has the ability to faithfully recreate aircraft motion using hydraulic legs. The cockpit is an exact replica of the aircraft being simulated. Electrocardiographic (ECG), skin conductance, and blood pressure monitoring was carried out throughout the test.

The pilot/patient acted as the captain or “pilot in command” and flew the aircraft from the left seat. A flight safety instructor acted as the copilot from the right seat. The flight scenario was from Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport, Arlington, Virginia to Dulles International Airport, Chantilly, Virginia. The pilot took off from Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport and flew 2 patterns, culminating in 2 “touch-and-go” landings to gain basic familiarity with the aircraft before proceeding to Dulles International Airport. The weather at Dulles International Airport was poor and at the minima for instrument approaches with continuous moderate turbulence. Approximately 5 miles from the “outer marker” (the point at which the pilot starts to descend toward the runway, approximately 6 minutes before landing), a catastrophic failure occurred in the left engine resulting in an engine fire and hydraulic failure (an actual potential failure mode in this type of aircraft). While the pilots were in the midst of the engine fire checklist, the glide slope of the approach was reached (signal to begin descent), mandating several configuration changes of the aircraft. Use of the 2 fire extinguisher devices in the left engine failed to extinguish the fire, leading to a continuous “master alarm” in the cockpit with loud aural alerts and flashing red lights. Because of the continued fire and the hydraulic problem, an immediate landing was mandatory. During the descent the pilot was subjected to a severe wind shear, requiring immediate and aggressive corrective control manipulation. This wind shear was short-lived, requiring immediate reversal of the changes made. Sestamibi was injected at that time calculated to be 1 minute before the time of landing or ground contact, with the latter defined as the point of maximal mental stress. The pilot was then transferred to an imaging facility. Imaging was carried out within 1 hour.

Standard 12-lead ECG recordings were performed every minute of exercise or mental stress. ST-segment values were measured 0.08 second from the J-point. Ischemia was defined as reversible ST-segment depression ≥1 mm compared to the PR segment with a horizontal or downsloping structure or ST-segment depression ≥1.5 mm with an upsloping structure. Rate–pressure product (RPP) was calculated as systolic blood pressure multiplied by heart rate. For comparison of RPP to ST-segment depression, sums of 11 leads were used per data point. For the nuclear study at rest thallium-201 3 mCi was injected and imaging begun in 20 minutes. During ES or AMS, technetium-99m sestamibi 30 mCi was injected 1 minute before peak stress. Images from a single-photon emission computed tomographic imaging camera (Toshiba, Tustin, California) were interpreted individually by 2 experienced readers who were blinded to condition (at rest, ES, or AMS). Differences were resolved by consensus. A 20-segment 5-point model was used: 0 = normal, 1 = mildly decreased uptake, 2 = moderately decreased uptake, 3 = markedly decreased uptake, 4 = no uptake. Ischemia was defined as worsening perfusion with stress compared to rest requiring a difference of summed perfusion scores of ≥3 points. Skin conductance was assessed to provide objective confirmation of autonomic arousal during all stress testing. Conductance was assessed using a digital coupler fastened to the distal phalanges of the index and middle fingers and recorded on a Davicon C20 EDR recorder (Davicon Corporation, Burlington, Massachusetts). Values were recorded as microsiemens per centimeter squared. Wilcoxon signed-rank test and paired t tests were used to test for changes in nuclear imaging, summed point scores, and hemodynamic values (JMP 7, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

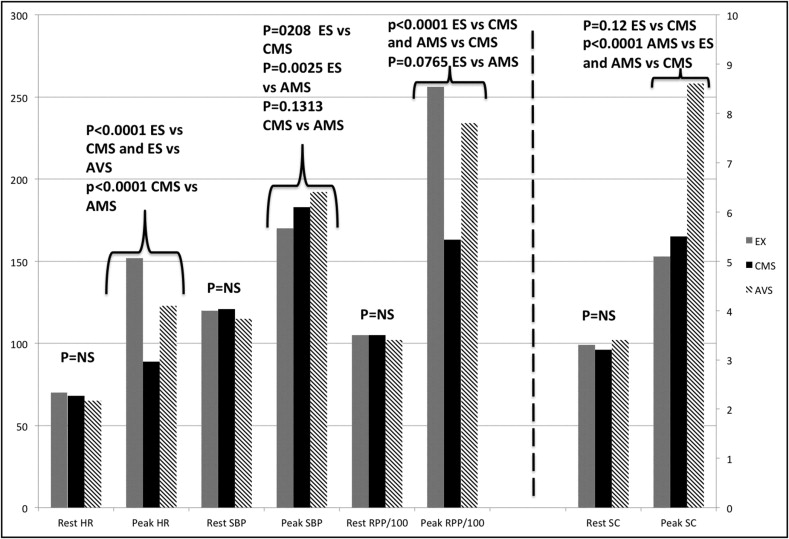

Sixteen airline pilots with a mean age of 58 years (range 42 to 62) were enrolled ( Table 1 ). All had significant coronary disease (≥1 major coronary artery with stenosis >75%), previous abnormal exercise test findings, and confirmation of ischemia by imaging techniques. All pilots completed the AMS protocol, 10 landing on the runway and 6 crashing on or near the runway. Mean heart rate, blood pressure, and RPP at rest were similar at the beginning of each testing procedure ( Figure 1 ). During ES subjects reached a higher heart rate than during AMS, but during AMS subjects achieved a higher systolic blood pressure ( Table 2 ). RPP was similarly increased in these 2 groups. CMS produced a lower heart rate response and RPP than the other groups. There were no differences in hemodynamic data (heart rate, blood pressure, or RPP) during AMS between pilots who had abnormal nuclear scans and those who had normal scans (p >0.2). All pilots developed gradual increases in heart rate and blood pressure during the flight sequence ( Figure 2 ).

| Pilot Number | Age/Sex | Flight Hours | HTN | HL | Previous MI | Previous PCI | Previous CABG | BB | Nitrates | ACEI | ASA | CCB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 42/M | 6,432 | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| 2 | 46/M | 6,944 | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | − |

| 3 | 50/M | 7,452 | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − |

| 4 | 52/M | 11,594 | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − |

| 5 | 53/M | 9,546 | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| 6 | 55/M | 13,490 | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 7 | 55/M | 15,400 | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| 8 | 56/M | 12,579 | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| 9 | 56/M | 14,849 | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| 10 | 57/M | 17,568 | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| 11 | 58/M | 16,451 | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| 12 | 58/M | 19,439 | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 13 | 59/M | 18,549 | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| 14 | 59/M | 19,002 | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| 15 | 60/M | 21,462 | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − |

| 16 | 62/M | 18,399 | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + |

| Pilot Number | Treadmill ES | CMS | AMS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max HR (beats/min) | Max SBP (mm Hg) | RPP | SC (μS/cm 2 ) | Max HR (beats/min) | Max SBP (mm Hg) | RPP | SC (μS/cm 2 ) | Max HR (beats/min) | Max SBP (mm Hg) | RPP | SC (μS/cm 2 ) | |

| 1 | 159 | 152 | 24,168 | 4.8 | 104 | 181 | 18,824 | 5.8 | 144 | 176 | 25,344 | 7.9 |

| 2 | 145 | 184 | 26,680 | 5.5 | 84 | 171 | 14,364 | 5.3 | 125 | 207 | 25,875 | 8.8 |

| 3 | 140 | 180 | 25,200 | 5.8 | 100 | 168 | 16,800 | 7.1 | 135 | 143 | 19,305 | 10.1 |

| 4 | 160 | 178 | 28,480 | 4.2 | 93 | 189 | 17,577 | 5.1 | 108 | 205 | 22,140 | 8.2 |

| 5 | 152 | 180 | 27,360 | 4.5 | 77 | 187 | 14,399 | 6.1 | 131 | 212 | 27,772 | 9.1 |

| 6 | 133 | 136 | 18,088 | 6.1 | 64 | 174 | 11,136 | 4.6 | 102 | 138 | 14,076 | 11.1 |

| 7 | 146 | 166 | 24,236 | 5.7 | 71 | 181 | 12,851 | 4.9 | 119 | 224 | 26,656 | 7.7 |

| 8 | 170 | 160 | 22,400 | 4.9 | 115 | 171 | 19,665 | 6.1 | 145 | 203 | 29,435 | 9.5 |

| 9 | 150 | 178 | 26,700 | 3.9 | 91 | 164 | 14,924 | 5.1 | 108 | 194 | 20,952 | 8.7 |

| 10 | 157 | 184 | 28,888 | 6.2 | 83 | 235 | 19,505 | 4.8 | 130 | 175 | 22,750 | 6.9 |

| 11 | 170 | 170 | 28,900 | 5.9 | 88 | 169 | 14,872 | 5.1 | 140 | 175 | 24,080 | 8.3 |

| 12 | 159 | 152 | 24,168 | 4.9 | 84 | 181 | 15,204 | 6.4 | 144 | 176 | 25,344 | 9.4 |

| 13 | 164 | 182 | 29,848 | 4.8 | 78 | 155 | 12,090 | 5.4 | 99 | 201 | 19,899 | 8.9 |

| 14 | 160 | 214 | 34,240 | 5.2 | 109 | 216 | 23,544 | 5.6 | 144 | 215 | 30,960 | 8 |

| 15 | 110 | 140 | 15,400 | 5.5 | 82 | 177 | 14,514 | 4.5 | 95 | 210 | 19,950 | 5.8 |

| 16 | 156 | 164 | 25,584 | 3.9 | 101 | 209 | 21,109 | 5.3 | 96 | 214 | 20,544 | 9.1 |

| Mean | 152 | 170 | 25,646 | 5.1 | 89 ⁎ | 183 ‡ | 16,336 ¶ | 5.5 ⁎ †† | 123 ⁎ † | 192 § ∥ | 23,443 # ⁎⁎ | 8.6 ‡‡ §§ |

⁎ p <0.0001 compared to treadmill;

† p <0.0001 compared to conventional mental stress.

‡ p = 0.0208 compared to treadmill;

§ p = 0.0025 compared to treadmill;

∥ p = 0.1313 compared to conventional mental stress.

¶ p <0.0001 compared to treadmill;

# p = 0.0765 compared to treadmill;

⁎⁎ p <0.0001 compared to conventional mental stress.

†† p = 0.1207 compared to treadmill;

‡‡ p <0.0001 compared to treadmill;

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree