Combined Iliac Stenting and Fem-fem Bypass

William C. Pevec

Currently, most patients with aortoiliac artery occlusive disease are treated with balloon angioplasty and stenting. Aortobifemoral artery bypass, the traditional “gold standard” of therapy, is commonly reserved for those patients with long occlusions of the aorta and/or iliac arteries, or if there is significant atherosclerotic plaque involving the common femoral arteries in conjunction with severe, bilateral aortoiliac disease.

Due to the successful endovascular treatment of extensive stenoses and occlusions of the iliac arteries, femoral–femoral artery bypass is now uncommonly performed for arterial occlusive disease. Combined iliac artery stenting and femoral–femoral artery bypass is indicated in patients with unilateral long occlusions of the common iliac and/or external iliac artery, with or without involvement of the ipsilateral common femoral artery, and stenosis or relatively focal occlusion of the contralateral (donor) iliac arteries, with or without contralateral (donor) common femoral artery stenosis. The donor arteries are treated with iliac artery angioplasty and stenting, with or without open common femoral artery reconstruction, and then a femoral–femoral artery bypass is performed to treat the extremity with the extensive iliac artery occlusion. This procedure is especially appropriate in patients who are poor candidates for aortobifemoral artery bypass due to medical comorbidities or prior abdominal or pelvic operations.

A history of disabling claudication, ischemic rest pain, or ischemic tissue loss is typically obtained. If the occlusive disease is confined to the aortoiliac segment, it is uncommon for the patient to experience rest pain or tissue loss; however, critical limb ischemia may be present if the aortoiliac disease is combined with occlusive disease of the common femoral and/or more distal arteries. Reconstruction of the aortoiliac disease alone is typically adequate to relieve claudication or rest pain, but healing of ischemic tissue loss usually requires restitution of inline flow to the affected foot.

The femoral pulse on the “recipient” limb (outflow limb for the femoral–femoral graft) is absent. The femoral pulse on the “donor” limb (inflow limb for the femoral–femoral graft) may be diminished or absent. A bruit will commonly be present over the pelvis and/or groin.

CT angiography, using a multidetector scanner, is typically superior to catheter angiography for treatment planning in patients with iliac occlusions; access for diagnostic arteriography may be difficult in the patient with bilateral iliac artery disease, and contrast opacification distal to long-segment iliac artery occlusions is typically poor. If there is concern for significant femoral or more distal arterial disease, contrast arteriography may provide better resolution than CT angiography for the evaluation of the common femoral, deep femoral, and infrapopliteal arteries. If both femoral artery pulses are absent, duplex scan of the iliac arteries can determine if one iliac system is patent. If one iliac system is patent, diagnostic arteriography via a femoral artery puncture can be performed. If there are bilateral iliac artery occlusions and diagnostic arteriography is needed, an upper extremity arterial access is preferred.

Positioning

The patient is placed in a supine position on a radiolucent operating table. A floating top fluoroscopy table is ideal. Portable C-arm fluoroscopy is acceptable, but imaging is better with a dedicated, fixed imaging system.

The entire abdomen should be sterilely prepared, along with the bilateral groins and proximal thighs, to allow for celiotomy in case of inability to cross a donor iliac artery occlusion, or in case of arterial perforation and hemorrhage that cannot be controlled with endovascular maneuvers.

Antibiotics to cover skin flora, typically cefazolin or vancomycin, are administered before making the skin incisions. If there are ischemic wounds on the distal lower extremity, antibiotic coverage should be expanded to treat gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria.

Technique

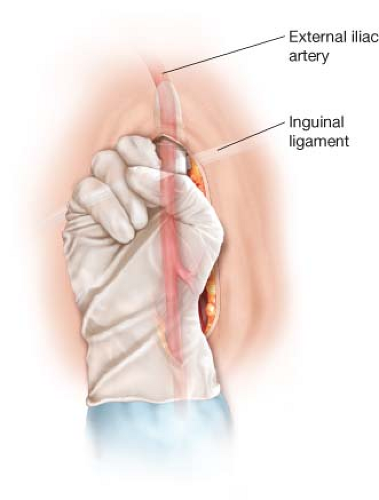

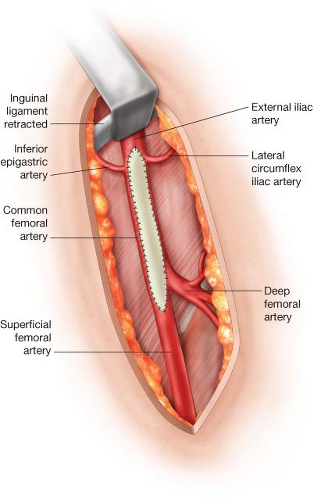

The bilateral common femoral artery bifurcations are circumferentially exposed via standard vertical groin incisions. The deep and superficial femoral arteries, if patent, should be mobilized beyond all palpable plaque. If there is extensive plaque in the donor common femoral artery or the donor external iliac artery, the inguinal ligament is mobilized and retracted cephalad, and the distal external iliac artery is exposed for 2 to 3 cm proximal to its inferior epigastric and lateral circumflex iliac branches. A mechanical retractor is very useful to maintain this exposure. The inguinal ligament can be divided if needed, but this is seldom necessary.

The surgeon’s index finger is used to begin the deep subcutaneous tunnel for the femoral–femoral graft. It is ideal to make this tunnel as early as possible after the common femoral arteries have been partially exposed, to allow hemostasis to occur in the tunnel before the administration of systemic heparin. The tunnel is created directly on the anterior surface of the external oblique fascia. This is especially important in obese patients. Creation of the tunnel more superficially, in the fat of the abdominal pannus, can lead to kinking and occlusion of the femoral–femoral graft. The tunnel is begun in the donor and recipient groins in a cephalad direction, parallel with the course of the common femoral and external iliac arteries (Fig. 4.1). The tunnels from each groin should continue in the cephalad direction for at least 6 to 8 cm before curving medially to meet at the midline. More oblique configurations of the tunnels may result in kinking of the graft as it travels from the femoral artery to the tunnel. The tunnel should be completed

entirely with blunt finger dissection; the surgeon’s index fingers should meet directly at midline. This can be difficult if there is a midline abdominal scar from a prior laparotomy; however, using an instrument to make tunnel can result in entry into the preperitoneal space or the peritoneal cavity, with risk of bladder or bowel injury. Once the surgeon’s index fingers have met, an umbilical tape mounted on a long Craaford clamp can be passed through the tunnel with direct guidance of the opposite index finger.

entirely with blunt finger dissection; the surgeon’s index fingers should meet directly at midline. This can be difficult if there is a midline abdominal scar from a prior laparotomy; however, using an instrument to make tunnel can result in entry into the preperitoneal space or the peritoneal cavity, with risk of bladder or bowel injury. Once the surgeon’s index fingers have met, an umbilical tape mounted on a long Craaford clamp can be passed through the tunnel with direct guidance of the opposite index finger.

If there is a prior midline scar, once the scar has been crossed by the surgeon’s fingers from each groin, the tunnel is bluntly widened in the cephalad and caudal directions, enlarging the diameter of the tunnel at the level of the midline scar. If this is not done, a kink will often develop in the femoral–femoral graft as the tunnel heals, as the tunnels from each groin are never perfectly aligned, and as each tunnel contracts around the graft, the graft may be “misregistered” on the midline, resulting formation of a kink in the graft.

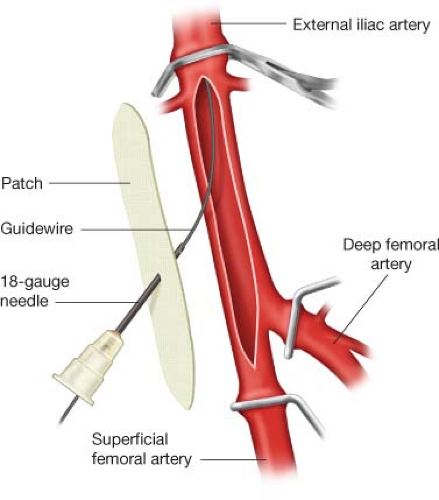

If the donor common femoral artery will require reconstruction, the reconstruction is typically completed before the donor iliac artery angioplasty and stenting are completed. However, if the donor external iliac artery is occluded, it is best to attempt wire passage before reconstructing the common femoral artery. If the plaque in the proximal common femoral or distal external iliac artery is divided, it becomes very difficult to cross the external iliac occlusion without the wire passing subintimally. Guidewire crossing of an occluded external iliac artery is usually easier if it attempted via puncture of the common femoral artery before the common femoral artery is repaired. Once the wire is successfully advanced into the aorta, the wire is left in place as the common femoral artery repair is completed. The distal end of the patch or graft used to reconstruct the common femoral artery is punctured with an 18-gauge needle, and then the backend of the wire is passed though the needle (Fig. 4.2). After the patch or graft repair is complete, the appropriate sheath is advanced over the wire, through the patch or graft, and into the common femoral artery.

If the donor common femoral artery is occluded, significantly stenotic, or diffusely calcified, the common femoral artery will require reconstruction before it can serve as the outflow for the iliac angioplasty and stenting and the inflow for the femoral–femoral graft. Repair may include endarterectomy and patch angioplasty or interposition grafting. When the common femoral artery is severely diseased, the plaque usually extends into the distal external iliac artery. Therefore, the proximal extent of the patch or the proximal anastomosis of the interposition graft should be on the external iliac artery, 1 to 2 cm proximal to the origins of the inferior epigastric and lateral circumflex iliac

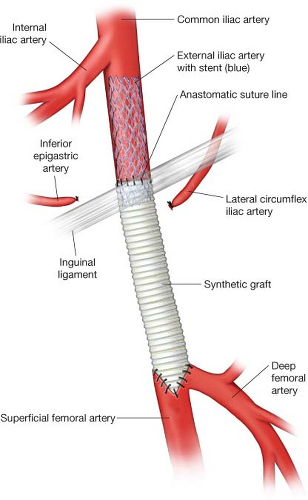

arteries (Fig. 4.3). If there is heavily calcified or thick plaque in the distal external iliac artery, an endarterectomy of the distal external iliac artery is performed. The proximal end of the plaque in the external iliac artery can be simply divided or fractured. The distal end of the subsequent external iliac artery stent is positioned to overlap the proximal end of the patch or graft, tacking down the more proximal, residual external iliac

plaque (Fig. 4.4). The distal end of the common femoral artery reconstruction should be sited on healthy segments of the common, superficial, and/or deep femoral arteries.

arteries (Fig. 4.3). If there is heavily calcified or thick plaque in the distal external iliac artery, an endarterectomy of the distal external iliac artery is performed. The proximal end of the plaque in the external iliac artery can be simply divided or fractured. The distal end of the subsequent external iliac artery stent is positioned to overlap the proximal end of the patch or graft, tacking down the more proximal, residual external iliac

plaque (Fig. 4.4). The distal end of the common femoral artery reconstruction should be sited on healthy segments of the common, superficial, and/or deep femoral arteries.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|