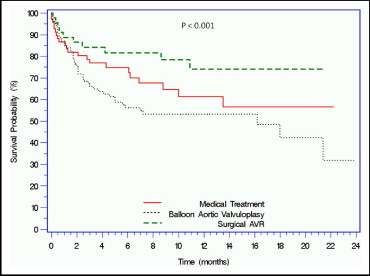

Patients with severe aortic stenosis and considered at high surgical risk or inoperable, and not eligible for a randomized clinical trial evaluating percutaneous aortic valve replacement (PAVR), were studied. Many of the patients referred to the study did not meet the inclusion criteria and/or had conditions listed in the exclusion criteria. These patients were then deferred to other treatment modalities. The study cohort consisted of 285 patients with severe aortic stenosis referred to participate in a clinical trial of PAVR. Patients were screened for eligibility on the basis of the protocol inclusion and exclusion criteria and deferred to other treatment modalities if they did not meet the enrollment criteria. Those patients were followed clinically by telephone contact or office visits. Of the 285 patients referred for PAVR, 216 (75.8%) were not included. The leading reasons for lack of eligibility were significant peripheral vascular disease in 50 (23.1%), Society of Thoracic Surgeons score <10% in 48 (22.9%), aortic valve area >0.8 cm 2 in 30 (13.9%), significant coronary artery disease in 25 (11.6%), and renal failure in 22 (10.2%). Sixty-nine of these patients (31.9%) were treated medically, 102 (47.2%) with balloon aortic valvuloplasty, and 45 (20.9%) with surgical aortic valve replacement. Major baseline characteristics were similar. Society of Thoracic Surgeons scores were lower in the surgical group compared with the medical and balloon aortic valvuloplasty groups (10.2 ± 2.5 vs 12.8 ± 3.3 vs 13.7 ± 3.3, respectively, p <0.001). During a median follow-up period of 175.5 days (range 55.7 to 344.75), the mortality rate was higher in the balloon aortic valvuloplasty group compared with the medical and surgical aortic valve replacement groups (46 [45.1%] vs 22 [31.9%] vs 10 [22.2%], respectively, p = 0.01). In conclusion, high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis who are deferred from PAVR often do poorly and incur high mortality rates, especially when treated with balloon valvuloplasty or medical therapy, while a loss of quality of life is apparent in those treated surgically.

Critical aortic stenosis affects an estimated 4.6% of individuals aged >75 years. The prognosis of patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis without surgical treatment is poor, with an average survival of only 1 to 3 years after symptom onset. Despite these facts, many symptomatic patients are not referred or are deferred because of high risk for surgery. Data from the Euro Heart Survey on Valvular Heart Disease revealed that up to 30% of patients with severe aortic stenosis did not undergo surgery, while others have reported higher rates, up to 41%. The high operative risk, multiple co-morbidities, and patient age are the main reasons for denial of surgery. Percutaneous aortic valve replacement (PAVR) was recently developed as an alternative treatment modality for these high-risk (Society of Thoracic Surgeons [STS] score >10 or logistic European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation [EuroSCORE] >20) or nonoperable patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. Many patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis screened for PAVR trials are not eligible on the basis of strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. The aim of this study was to determine the main reasons for the lack of eligibility for PAVR and to explore the clinical outcomes of those patients referred to other treatment modalities.

Methods

This prospective, observational cohort study was approved by the institutional review board of our institution. Included were patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis who were referred for consideration for a randomized trial of PAVR from April 2007 to July 2009. All were screened and consented to the study. This report describes those patients not randomized either because of failure to satisfy inclusion criteria or because they met criteria for exclusion and were deferred to other treatment modalities.

The screening included an interview, clinical examination, electrocardiography, laboratory assessment, standard 2-dimensional echocardiography, anatomic examination, and Doppler examination. Measurements were performed according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography. To assess the severity of aortic stenosis, the peak velocity (continuous-wave Doppler) over the aortic valve, the mean echocardiographic gradient, and the echocardiographic aortic valve area were calculated. All patients underwent left and right cardiac catheterization, and the peripheral vascular tree was assessed by digital subtraction angiography with a marker pigtail for quantitative coronary analysis. A 4Fr catheter was left in the abdominal aorta, and the patient was taken to the 64/256 computed tomography suite for noncontrast computed tomography of the chest and abdomen, followed by contrast computed tomography of the abdominal aorta and iliacs with 10 to 12 ml injected in the abdominal aorta. The STS score and the logistic EuroSCORE were calculated using Web-based systems ( http://209.220.160.181/STSWebRiskCalc261/de.aspx and http://www.euroscore.org , respectively). Each patient was evaluated by and discussed among a team of cardiologists and cardiac surgeons for the determination of surgical eligibility. The data from patients rejected from the trial were prospectively entered into a dedicated database. All patients were followed by telephone contact or office visit.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD and categorical variables as percentages. The follow-up days are presented as median (interquartile range). Differences between continuous variables were assessed using Student’s t test. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests as indicated. To compare the different groups, 1-way analysis of variance was used. Differences were considered significant at p <0.05. Cumulative survival is presented as Kaplan-Meier curves using the log-rank statistic.

Results

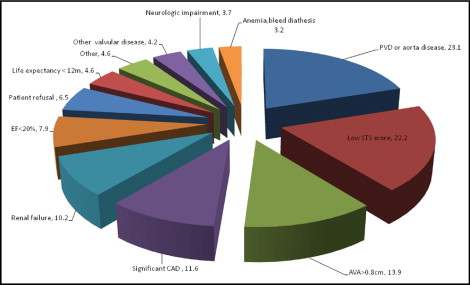

From April 2007 to March 2009, 285 patients with severe aortic stenosis were referred for participation in a PAVR trial being conducted at our institution. A total of 216 patients (75.8%) could not enter into the trial. Of these 216 patients, 32 (14.8%) had 2 exclusion criteria causes, and 2 (0.9%) had 3 exclusion criteria causes. The main exclusion criteria were peripheral vascular or aorta disease in 50 (23.1%), low STS score <10% in 48 (22.9%), aortic valve area >0.8 cm 2 in 30 (13.9%), significant coronary artery disease requiring revascularization in 25 (11.6%), and renal failure in 22 (10.2%) ( Figure 1 ). Of the total group screened, in 4 patients (1.85%), malignant tumors were found on cardiac tomography during screening evaluation.

The baseline, laboratory, and hemodynamic parameters of the ineligible cohort are listed in Table 1 . These patients were referred to 1 of 3 treatment modalities according to the physician’s discretion: 69 (31.9%) to medical treatment, 102 (47.2%) to balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV), and 45 (20.9%) to surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR) ( Figure 2 ). The groups had similar baseline characteristics for age, coronary artery disease, and cardiac risk factors. The surgical AVR group had lower operative mortality as calculated by the STS score and logistic EuroSCORE and a lower prevalence of renal failure compared to the medical and BAV groups. New York Heart Association class was significantly higher in the BAV group compared to the medical and surgical AVR groups.

| Variable | Medical Treatment | BAV | Surgical AVR | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 69) | (n = 102) | (n = 45) | ||

| Age (years) | 81.7 ± 8.7 | 81.1 ± 9.3 | 79.5 ± 9.1 | 0.62 |

| Women | 39 (56.5%) | 54 (52.9%) | 19 (42.2%) | 0.13 |

| Society of Thoracic Surgeons score | 11.0 ± 5.5 | 12.7 ± 6.7 | 7.6 ± 5.0 | <0.001 |

| Standard EuroSCORE | 12.8 ± 3.3 | 13.7 ± 3.3 | 10.2 ± 2.5 | <0.001 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE | 35.1 ± 22.3 | 45.4 ± 22.6 | 21.0 ± 14.2 | <0.001 |

| New York Heart Association classes III and IV | 50 (72%) | 95 (88%) | 21 (47.5%) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 27.1 ± 5.7 | 26.2 ± 7.6 | 28.3 ± 6.9 | 0.16 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 (31.8%) | 33 (32.3%) | 16 (35.5%) | 0.93 |

| Hypertension | 56 (81.1%) | 97 (95.1%) | 40 (88.8%) | 0.60 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 51 (73.9%) | 79 (77.4%) | 31 (68.9) | 0.67 |

| Coronary artery disease | 47 (68.1%) | 73 (71.5%) | 27 (60%) | 0.44 |

| Smokers | 18 (26.1%) | 33 (32.3%) | 15 (33.3%) | 0.33 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 20 (28.9%) | 37 (36.2%) | 11 (24.4%) | 0.25 |

| Renal failure | 28 (40.5%) | 45 (44.1%) | 9 (20%) | 0.004 |

| Previous cerebrovascular accident | 8 (11.6%) | 22 (21.5%) | 5 (11.1%) | 0.15 |

| Arrhythmia | 23 (33.3%) | 45 (44.1%) | 14 (31.1%) | 0.67 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 19 (27.5%) | 42 (41.2%) | 12 (26.6%) | 0.12 |

| Previous coronary artery bypass grafting | 22 (31.9%) | 34 (33.3%) | 10 (22.2%) | 0.44 |

| Previous percutaneous coronary intervention | 7 (10.1%) | 18 (17.6%) | 4 (8.8%) | 0.34 |

The medical treatment group and BAV group had significantly lower levels of hematocrit and significantly higher levels of creatinine and B-type natriuretic peptide compared to the surgical group. There was no significant difference in C-reactive protein among the 3 groups ( Table 2 ). The mean aortic valve area was significantly lower in the BAV and surgical AVR groups compared to the medical group (0.69 ± 0.13 and 0.72 ± 0.19 vs 0.82 ± 0.2 cm 2 , respectively, p <0.001). In the surgical group, the ejection fraction and the mean and peak gradients across aortic valve were higher compared to the medical and BAV groups. Pulmonary artery systolic pressure was significantly higher in the BAV group compared to the medical and surgical AVR groups.

| Variable | Medical Treatment | BAV | Surgical AVR | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 69) | (n = 102) | (n = 45) | ||

| Laboratory values | ||||

| Hematocrit (%) | 35.7 ± 4.5 | 35.7 ± 4.4 | 39.0 ± 4.4 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin level (mg/dl) | 11.7 ± 1.6 | 11.5 ± 1.6 | 12.9 ± 1.6 | <0.001 |

| Platelets (×10 6 /ml) | 209.7 ± 92.6 | 202.0 ± 80.5 | 203.1 ± 84.7 | 0.68 |

| White blood cell (×10 3 /ml) | 7.7 ± 3.0 | 9.3 ± 13.7 | 7.3 ± 2.3 | 0.2 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 0.001 |

| Sodium (mg/dl) | 138.1 ± 4.1 | 135.8 ± 5.7 | 137.9 ± 3.5 | 0.43 |

| Cardiac troponin I (ng/ml) | 0.10 ± 0.6 | 0.11 ± 0.2 | 0.03 ± 0.06 | 0.13 |

| Creatine kinase-MB (U/L) | 1.17 ± 1.7 | 1.14 ± 0.8 | 0.76 ± 0.5 | 0.22 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dl) | 10.6 ± 21.2 | 18.2 ± 27.5 | 13.7 ± 30.4 | 0.41 |

| B-type natriuretic peptide (pg/ml) | 1209.0 ± 775.4 | 1766.1 ± 1307.5 | 886.6 ± 796.9 | 0.02 |

| Echocardiographic data | ||||

| Ejection fraction (%) | 49.7 ± 16.3 | 47.4 ± 18.3 | 58.2 ± 12.6 | 0.003 |

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (mm Hg) | 45.6 ± 15.9 | 54.5 ± 17.6 | 43.3 ± 16.0 | 0.006 |

| Aortic valve area (cm 2 ) | 0.82 ± 0.2 | 0.69 ± 0.13 | 0.72 ± 0.19 | <0.001 |

| Maximum velocity across aortic valve (m/s) | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| Mean gradient across aortic valve (mm Hg) | 38.7 ± 16.5 | 40.8 ± 12.3 | 49.7 ± 19.7 | 0.003 |

| Peak gradient across aortic valve (mm Hg) | 61.5 ± 26.5 | 67.9 ± 20.1 | 80.8 ± 33.9 | 0.002 |

| Right-sided cardiac hemodynamic parameters | ||||

| Aortic valve area (cm 2 ) | 0.80 ± 0.25 | 0.65 ± 0.53 | 0.57 ± 0.18 | <0.001 |

| Mean gradient across aortic valve (mm Hg) | 37.4 ± 15.8 | 48.0 ± 18.1 | 55.6 ± 20.8 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (mm Hg) | 49.0 ± 15.6 | 54.9 ± 15.3 | 45.2 ± 20.0 | 0.009 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 4.6 ± 1.4 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 0.02 |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m 2 ) | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 2.37 ± 0.4 | 0.34 |

| 2- or 3-vessel coronary disease | 39 (56.5%) | 42 (41.2%) | 14 (31.1%) | 0.007 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree