Chapter 69

Classification and Natural History of Vascular Anomalies

Carolyn R. Rogers, John B. Mulliken

Based on a chapter in the seventh edition by Byung-Boong Lee and Leonel Villavicencio

Vascular surgery matured as a specialty of general surgery during the twentieth century while the field of vascular anomalies remained obscured by a cloud of confusing nomenclature. This haze of bewildering nosology lifted during the last quarter of that century to reveal a truly interdisciplinary field that overlaps many specialties, including vascular surgery.

Traditionally, vascular surgeons manage disorders of anatomically named arteries and veins. Only a few vascular surgeons, most of them European, have focused part of their practice on malformations distal to the main vascular trunks, particularly those in the extremities. Noteworthy in this regard are the names Malan, Schobinger, Servelle, Azzolini, Belov, Loose, and Matassi. In the mid-1970s, several of these vascular surgeons joined like-minded colleagues from other specialties to initiate a workshop for the study of vascular anomalies—this grew to become the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA). The early gatherings of this organization were punctuated by heated discussions about terminology. Finally, there was a consensus at the 1996 meeting in Rome, and the ISSVA classification was accepted by the membership.1

Nosology

The earliest terminology for vascular anomalies was descriptive. Words such as “strawberry mark,” “port-wine stain,” and, “cherry angioma” referenced food because the mother was blamed for imprinting her unborn child. With the ascent of histopathology in the nineteenth century, all vascular anomalies were called “angiomas” or “lymphangiomas.” With increasing knowledge of cardiovascular embryology in the early twentieth century, vascular anomalies were envisioned as disorders of faulty development. Nevertheless, when put to the test of clinical usefulness, embryologic classifications failed to differentiate between vascular anomalies that regress and those that progress and, thus, offered little help in guiding management.

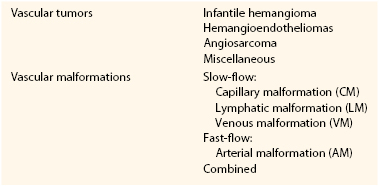

A prospective study by Mulliken and Glowacki2 defined cellular features of vascular anomalies using histochemistry, radiography, and electron microscopy. This investigation delineated two major categories of vascular anomalies: tumors, which exhibit endothelial hyperplasia; and malformations, which have normal endothelial turnover unless disturbed. This binary “biologic” system became the foundation of the ISSVA classification (Table 69-1).

Table 69-1

International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) Classification of Vascular Anomalies

Vascular malformations are structural anomalies, inborn errors of vascular morphogenesis. A single type of channel anomaly may predominate; however, often the malformed channels are combined forms. Vascular malformations are subcategorized on the basis of rheology and channel architecture as slow-flow (capillary, lymphatic, or venous), fast-flow (arterial), or combined. These malformations are more likely to be referred to vascular surgeons than are vascular tumors. The consultant must be wary because vascular tumors can masquerade as vascular malformations in various hues of pink, red, and blue. An estimated 54% of vascular malformations and 30% of vascular tumors in patients referred to one center between 1999 and 2010 were initially diagnosed incorrectly.3

Vascular Tumors

The spectrum of vascular tumors ranges from common infantile hemangiomas to uncommon lesions of borderline malignancy to rare malignant neoplasms (see Chapter 70). Unlike vascular malformations (and other vascular tumors), infantile hemangiomas are immune-positive for glucose transporter protein-1 (GLUT-1).4,5 Because most infantile hemangiomas arise in the head/neck region, vascular surgeons are unlikely to be asked for consultation. Vascular surgeons might be asked to opine on a rare variant of the common infantile tumor that has a predilection for the lower extremities called “reticular hemangioma.” This lesion is associated with intractable ulceration, anogenito-urinary-sacral anomalies, and sometimes cardiac overload. Reticular hemangioma of the lower limb can be confused with vascular malformations, such as capillary malformation, cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita, and Parkes Weber syndrome.6 Congenital hemangiomas constitute a special category of vascular tumors that are fully grown at birth, behave differently from infantile hemangiomas, and are GLUT-1 negative. There is rare vascular tumors that are categorized as borderline malignant called hemangioendotheliomas and angiosarcomas.

The doubly eponymic “Kasabach-Merritt” thrombocytopenia has been wrongly associated with infantile hemangioma. This disorder of platelet trapping occurs only with kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma, not with common infantile hemangiomas.7–9 Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon has also been used incorrectly to describe the localized intravascular coagulopathy that occurs with extensive venous malformations; this is an entirely different hematologic disorder.10

Vascular Malformations

Vascular malformations are, by definition, congenital, and most are obvious at birth (see Chapters 71 and 72). However, some vascular malformations are undetectable at birth and manifest in childhood, adolescence, or adulthood. Vascular malformations arise because of abnormal signaling processes regulating proliferation, differentiation, maturation, adhesion, and apoptosis of vascular cells, including endothelium, smooth muscle, and pericytes.11 Some are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, whereas others occur sporadically and are caused by somatic (postzygotic) mutations.

Slow-Flow Malformations

Capillary Malformation

Capillary malformation (CM) must be differentiated from the common fading macular stain naevus flammeus neonatorum (“angel’s kiss” or “stork bite”) frequently present in a newborn on the face and nuchal region. Capillary malformations (still often called “port-wine stains”) are red macular lesions seen at birth that persist throughout life. They are histopathologically characterized by thin-walled capillary- to venule-sized channels in the papillary and upper reticular dermis with deficient perivascular neural elements. Facial CM often darkens, thickens, and develops a cobblestone appearance in adulthood. In contrast, CM in the trunk and limbs deepens in color with age but does not become nodular, although adjacent veins often become more prominent. Capillary malformations occur in association with several disorders; the best known is Sturge-Weber syndrome.

Sturge-Weber Syndrome.

Sturge-Weber syndrome is characterized by leptomeningeal vascular anomalies and facial CM, commonly manifesting as seizures and glaucoma. The clinical course is highly variable; some children have intractable seizures, behavioral issues, mental retardation, and recurrent stroke-like episodes. Soft tissue overgrowth in the area of facial CM occurs with age. More than half of patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome have noncontiguous, patchy CMs on the torso and extremities.12 Fifteen percent of patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome and extracranial staining have hypertrophy of an extremity.13 Varicose veins are seen in the stained areas in older patients with this disorder.

Cutis Marmorata Telangiectatica Congenita.

The vascular anomaly known as cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (CMTC) manifests in a neonate as serpiginous, reticulated bands of deep purple color with localized cutaneous atrophy and often ulceration. The lesions occur in a localized or regional pattern. The legs are most frequently involved; there may be subcutaneous hypoplasia or hypertrophy. The patient with leg involvement may be referred to a vascular surgeon because of concern about vascular occlusion in the limb. There have been rare case reports of hypoplasia of the iliac and femoral veins14 and of iliac arterial stenosis, including stenosis in the unaffected limb.15 Predictably, CMTC shows improvement during the first year of life that continues throughout childhood. Cutaneous atrophy and vascular staining persist, usually with venous ectasias in the involved limb.

Macrocephaly–Capillary Malformation.

Macrocephaly–capillary malformation (M-CM) is characterized by faint CM of the upper lip and scattered staining over much of the body in association with overgrowth, syndactyly or postaxial polydactyly, connective tissue dysplasia of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and joints, and cortical brain malformations, typically polymicrogyria and megalencephaly/macrocephaly.16 This condition was initially mistakenly called “macrocephaly–cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita.” Affected patients do not have CMTC; rather, they have diffuse, reticulate capillary staining that fades.17 Patients with M-CM may be referred to a vascular surgeon because their signs and symptoms are often confused with those of combined vascular malformation/overgrowth syndromes.

Venous Malformation

For many years, vascular malformations (VMs) were called “cavernous hemangiomas;” this practice caused confusion with vascular tumors. Although present at birth, VMs may not be obvious and appears later as bluish, compressible swellings. They are histopathologically characterized by thin-walled interconnected vessels or pouches with abnormal investing smooth muscle. VMs often develop thrombi and later phleboliths. Venous anomalies are typically painful, especially in the morning and when an affected limb is dependent. An extensive VM of the limb is known by the old eponym “genuine diffuse phlebectasia of Bockenheimer,”18 in which all soft tissues and long bones are affected. Leg length discrepancy may result, causing pelvic tilt, scoliosis, and gait disturbance.

The blood contained in a large or extensive VM exhibits a localized intravascular coagulopathy—that is, slight decrease in platelets (100,000 to 150,000/mm3), normal PT and aPTT values, low fibrinogen content (150-200 mg/dL), and elevation of fibrin split products (D-dimer).9 Affected patients are at risk for development of a systemic coagulopathy following trauma or surgical intervention; the hematologic findings are similar to those in disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. If a patient presents with a lesion of uncertain vascular nature, elevation of D-dimer can be used as a diagnostic tool to differentiate large VM from another vascular lesion, such as glomuvenous malformation (normal D-dimer), arteriovenous malformation, or lymphatic malformation. D-dimer measurement can also differentiate a slow-flow disorder, such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, from a fast-flow disorder, such as Parkes Weber syndrome.19 Low-molecular-weight heparin may be given to treat the pain caused by localized intravascular coagulopathy and to prevent decompensation to a systemic coagulopathy prior to an operation.10

Glomuvenous Malformation.

A genetic diagnosis should be considered whenever there is a family history of VM, particularly multiple lesions. Glomuvenous malformation (GVM) is the most common heritable VM; it is autosomal dominant. Once known as “glomangiomas,” GVMs are clinically distinguished from common VMs because they have a cobblestone appearance and are painful on palpation.20 Also, unlike VMs, GVMs in limbs do not respond to elastic compressive garments and there is rarely deep extension. The lesions can be small or extensive and plaque-like, particularly on the trunk and extremities. They range from pink in infants to deep blue or purple in children and adults. Seventy-eight percent are located on the extremities.21 Histologically, GVMs have pathognomonic glomus cells within the walls of distended vein-like channels.

Cutaneomucosal Venous Malformation.

Patients with this hereditary disorder known as cutaneomucosal venous malformation (CMVM) typically have small, multifocal, soft, compressible cutaneous lesions appearing in various shades of blue. Unlike GVMs, these lesions are often present on mucosa, typically on the lips and tongue, and may occur in skeletal muscle. There may also be progressive venous ectasia in the neck and upper limb. Fifty percent of CMVMs are located in the cervicofacial area, and 37% on the extremities.21

Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome.

Soft, blue, nodular-appearing cutaneous and gastrointestinal VMs characterize blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Lesions increase in size and number with age. Gastrointestinal VMs can cause life-threatening bleeding. The genetic cause of this disorder is most likely a postzygotic mutation.

Lymphatic Malformation

Lymphatic malformations (LMs) are clinically and radiologically categorized as microcystic, macrocystic, or combined. These anomalies were previously described with terms such as “lymphangioma” (microcystic LM), “cystic hygroma” (macrocystic LM), and “lymphangiomatosis” (visceral LM). They are composed of anomalous channels or pockets of lymphatic fluid, often with overlying cutaneous lesions. The walls are of variable thickness with smooth and striated muscle components and nodular collections of lymphocytes. The spectrum of LMs is quite variable. Most LMs manifest in the infantile period. Deep LMs appear as generalized swellings to localized areas of overgrowth. Expansion is rapid if infection or intralesional bleeding occurs. Cutaneous LMs most often involve the chest and upper limbs, less often the lower limbs. They manifest as clear or dark red vesicles (due to intravesicular bleeding). Visceral LMs may go undetected until rapid expansion occurs. Congenital lymphedema is a type of LM that typically involves the lower limbs.

Congenital Lymphedema.

Primary (congenital) lymphedema is caused by anomalous lymphatic channels and must be differentiated from secondary (acquired) lymphedema due to injury to the lymph nodes or vessels (from operation, radiation, trauma, etc.) (see Chapter 66). Primary lymphedema is often nonfamilial, but it can be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, in which case it is also known as Milroy disease. This condition manifests shortly after birth in 49% of patients, during childhood in 10%, or during adolescence in 41%. Congenital lymphedema manifests as gradually progressive swelling of an extremity, most often the lower extremities (92%). Cellulitis affects 19% of patients and is often recurrent.22 Over time, soft tissue overgrowth develops because of fatty deposition and fibrosis. Compression is the mainstay of initial treatment; suction lipectomy has also been used.22–24 There are reports of success following microvascular lymphaticovenous anastomosis.25,26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree