Chapter 56

Chronic Venous Disorders

Nonoperative Treatment

Luigi Pascarella, Cynthia Shortell

Based on a chapter in the seventh edition by Gregory L. Moneta and Hugo Partsch

Chronic venous disease (C2-C6 disease) of the lower extremity is one of the most common diseases in western Europe and the United States. The manifestations of chronic venous disease can be different and may encompass telangiectasias, reticular veins, varicose veins, lipodermatosclerosis, and venous ulcers. Its prevalence reported in studies from different countries ranges from 2% to 56% in men and 1% to 60% in women.1 In the Edinburgh Vein Study, varicose veins were present in 40% of men and 16% of women, ankle edema was found in 7% of men and 16% of women, and ulcers were seen in 1% of men and women. In the same study, the incidence of superficial vein reflux was noted to be 9.4% in men and 6.6% in women and to increase with age.2,3 The incidence of all clinical manifestations of venous disease also increases with age.2–4 In the United States, it has been estimated that 20% of patients with chronic venous disease develop venous ulcers, and 50% require treatment periods of more than 1 year.2,3

The high prevalence and significant morbidity of chronic venous disease have an important socioeconomic impact, making the appropriate choice of therapy critical to cost-effective care. The disease is progressive and has a high incidence of recurrence, especially in its most advanced stages. In France, the expenditure for patients with chronic venous disease was reported to be €2.24 billion per year in 1991, 34% of which was incurred by inpatient treatment.4 In this study, chronic venous disease was the eighth most common cause of admission, accounting for 2.6% of the health care budget.4 The impact of more advanced stages of chronic venous disease is even greater. A cost analysis from the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in 1999 examined the inpatient and outpatient costs of a cohort of 78 patients with active venous ulcers from the initiation of treatment until complete healing.5 A total of 71 patents (91%) healed during the study. Fourteen patients underwent 18 hospitalizations for venous ulcer care. The average total medical cost per patient was $9685 (median, $3036), inflated to $16,524 in 2011 U.S. dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Medical Care with an average monthly cost of $4095. In another review using the Consumer Price Index for Medical Care, it was observed that the cost to achieve complete healing at 12 weeks was approximately $1357 and significantly increased to $30,765 for more than 12 weeks of treatment.6,7 Overall it was estimated that in the United States, the annual cost for venous ulcer treatments ranges from $1.5 to $3.0 billion, with the greatest burden on the Medicare system. These costs do not include decreases in mobility and work capacity, patients’ out-of-pocket expenses, and adverse psychological effects related to venous ulcers.7

Whereas the definitive treatment of chronic venous disease includes the ablation of appropriate refluxing veins when it is clinically indicated, the initial treatment of chronic venous disease has traditionally been nonoperative with the main goal of symptom control and quality of life improvement. In addition, conservative measures are currently mandated by most third-party payers in the United States before approval of therapeutic surgical interventions. In this setting, the success of conservative management has long been considered to be a contraindication to more definitive surgical treatments. However, a quality of life analysis from Lurie and Kistner8 questions the validity of this approach. In this study, the authors compare the outcomes of surgical therapy in patients with favorable and unfavorable responses to initial conservative management using the Specific Quality of Life and Outcomes Response–Venous questionnaire. Patients who improved with conservative therapy and who elected to proceed with surgical correction were more than 15 times likely to improve with surgery at 1 month and 21 times at 12 months of follow-up compared with those who did not improve with conservative thereapy.8,9 The authors concluded that conservative therapy should be used as a benchmark to predict success after surgical therapy rather than as a contraindication to definitive intervention.8,9

Nonoperative Treatment of Chronic Venous Disease

The nonoperative approach to patients with chronic venous disease includes lifestyle modification, compression, and pharmacologic therapies.

Lifestyle Modification

The most common initial recommendations for lifestyle modification in patients with chronic venous disease are avoidance of vigorous exercise and leg elevation.10

Exercise

In a review of the most current literature, Brown10 concluded that although vigorous exercise may increase the likelihood of venous ulcerations, increased mobility and moderate physical activity may be beneficial for ulcer healing and may be an adjunct to compression therapies. Overall, patients with chronic venous disease should be encouraged to engage in regular moderate physical activity.10 In a study by Roaldsen et al,11 it was observed that walking speed, endurance, and self-perceived exertion were significantly lower in 34 women aged 60 to 85 years with current or previous ulcers compared with age-matched controls. It was also noted that ankle plantar flexion and dorsiflexion motions were significantly reduced in patients with active ulcers, mostly because of pain. In another study from the same authors, patients with low levels of physical activity displayed stronger fear avoidance beliefs and more pain than those with higher levels of physical activity.10,11 These findings and observations from other studies emphasize the need for physical therapists to be highly involved in the care of patients with advanced C4-C6 disease, highlighting the importance of adequate pain control and a supervised exercise program tailored to improve ankle mobility and overall functional ability.10

Leg Elevation

Leg elevation has been shown to aid venous drainage, to increase the venous return to the heart, and to reduce ankle edema.10 Patients with significant chronic venous disease are advised to elevate their legs 30 cm above the heart several times during the day.10 In addition, enhancement of cutaneous microcirculation has been shown by Coleridge Smith12 through Doppler fluxmetry in patients with lipodermatosclerosis after leg elevation, with a median 45% Doppler flux increase. Transcutaneous tissue oxygen saturation levels have been used as an indicator of skin perfusion. These have been found to be reduced in patients with venous ulcers.13 Several authors have reported higher transcutaneous tissue oxygen saturation levels with compression strategies, standing position, and ambulation compared with leg elevation with or without compression. It is unclear how the transcutaneous tissue oxygen saturation levels correlate with ulcer healing.13 A retrospective Australian study of 122 patients with previous venous ulcers observed for 12 to 40 months found that significantly lower rates of recurrence were associated with compression therapy and longer leg elevation times (33 minutes/day).14 Recurrence was observed with a 14-minute/day period of leg elevation.14 The authors of the study recognized limitations due to the retrospective design of their analysis and possible response bias as all the measures of physical activity, psychosocial scales, and self-care activities were obtained from self-report questionnaires.14

Leg elevation seems to be beneficial in symptom control in all patients with chronic venous disease. There is a trend supporting some advantage in ulcer healing, despite the evidence of level 1 and level 2 studies.10 In addition, the utility of leg elevation is limited by the practical difficulty of prolonged leg elevation for many patients.

Compression Therapy

Compression therapy is an essential component of the care of patients with chronic venous disease (C2-C6). The rationale of graded external compression is to oppose the main pathogenetic factor underlying chronic venous disease, reflux-induced venous hypertension,15 but compression therapy has been found to have a number of additional benefits. Given a normal standing resting venous pressure of 60 to 80 mm Hg, major hemodynamic effects can be expected with an interface compression of 35 to 40 mm Hg. External compression of more than 60 mm Hg has been found to occlude lower extremity veins in standing individuals.15 Therefore, 60 mm Hg has been considered the safe upper limit for externally applied sustained compression as shown by dermal blood flow investigations, even in patients with an ankle-brachial index above 0.5 and absolute ankle pressure higher than 60 mm Hg.15–17

Compression therapy has also been shown to improve venous pump function. Enhanced venous flow velocities have been noted with low-grade interface pressure of 15 to 25 mm Hg with prevention of thromboembolic events in supine patients.15 The biomolecular mechanisms by which compression therapy functions are unclear. Animal and clinical studies have documented that compression therapy improves cutaneous microcirculation.18 Video capillary microscopy showed an increase in capillary density with decreased capillary diameter and pericapillary halo in 20 patients with varicose veins and lipodermatosclerosis treated with compression therapy.18 Several authors have also noted enhancement of lymphatic drainage and cutaneous oxygenation as demonstrated by increased transcutaneous tissue oxygen saturation levels.13,19,20 Decreased serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-α and vascular endothelial growth factor have been observed in patients with healing ulcers treated with four-layer graduated compression.21 The improved cutaneous microcirculatory environment has been thought to promote venous ulcer healing as has been clearly proved by several studies.19,22,23

A number of compression garments are available. These include graduated elastic stockings and the CircAid garment, paste gauze boots (Unna boot), layered elastic and nonelastic compression bandages, and intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC).

Gradient Elastic Stockings and CircAid Garment

Gradient elastic stockings were first developed in the 1950s; they are currently manufactured by several companies and are available in various strengths and lengths. The compression applied by the stocking is calculated on the basis of the mechanical properties of the fabric used by each manufacturer. The pressure applied on the ankle by the stocking is expressed as a range and is a function of in vitro measurements based on leg circumferences.

Graduated compression stockings are currently available in four tensions: 10 to 15 mm Hg (class 1; over-the-counter); 20 to 30 mm Hg (class 2; prescription); 30 to 40 mm Hg (class 3; prescription); and 40 to 50 mm Hg (class 3—high compression; prescription). They are also available in different lengths as knee-high, thigh-high, and panty hose. They are fitted on the basis of measurements of circumference, usually at thigh, midcalf, and ankle levels, and may be individually customized in patients with atypical leg morphology, such as may be seen in the obese or patients with advanced chronic venous disease. Compression garments should be replaced every 6 to 9 months as the elasticity is lost after this time.22

Gradient Compression Stockings in C1-C2 Disease

A number of studies have reported the efficacy of gradient elastic stockings in early and advanced stages of chronic venous disease. In a prospective randomized multicenter trial conducted in France of 125 women with CEAP classification of C1-3SEpAs1-5, it was noted that regular wearing of graduated compression stocking (10-15 mm Hg) during a 15-day period was associated with significant symptom control when a high level of compliance in wearing the hose was achieved.24 In a review of 11 prospective randomized trials, 12 nonrandomized studies, and 2 guidelines, no agreement was found regarding the appropriate class of compression for the management of early chronic venous disease stages.25 Compression improved symptoms in patients with uncomplicated symptomatic varicose veins when high compliance was reached.25 However, use of compression stockings was not shown to prevent disease progression or recurrence of varicose veins after treatment.25 The same review highlighted also that the majority of the published literature was often contradictory and had methodologic flaws and that the results of several studies were confounded by a high number of noncompliant patients.25

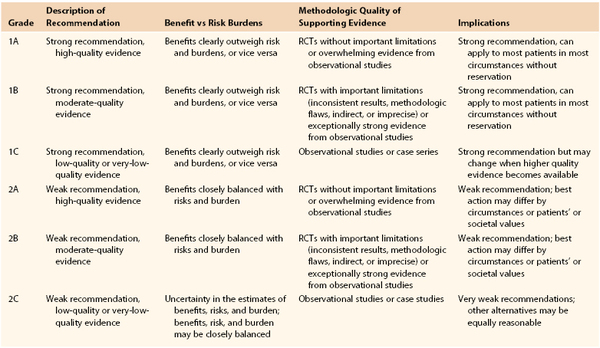

It can be concluded that wearing of light compression stockings with a pressure below 20 mm Hg may be beneficial in the following indications (Table 56-1)17: symptom control in C1s (grade 1B); varicose veins in pregnancy (grade 1B); prevention of leg edema related to prolonged sitting and standing (grade 1B); and prevention of venous thromboembolism in nonambulatory patients or after surgery (grade 1A). The recommendation for use of class 2 compression stockings in uncomplicated symptomatic varicose veins is also weak (grade 2B) and only for symptom relief.17 Class 2 stockings have also been found to be poorly associated with prevention of varicose veins after surgery and treatment of venous ulcers (grade 2B).17

Surgery versus Compression in C2-C3 Disease

In the randomized clinical trial, observational study, and assessment of cost-effectiveness of treatment of varicose veins (REACTIV trial), 357 patients were randomized to three groups: group 1 (n = 34), minor varicose veins, conservative management versus sclerotherapy; group 2 (n = 77), moderate varicose veins with reflux, conservative management versus surgery; and group 3 (n = 246), severe varicose veins with reflux, conservative treatment versus surgery.26 Conservative treatment included lifestyle modification, leg elevation, and compression stockings; the surgery arm included high ligation of the saphenofemoral junction, saphenous vein stripping, and phlebectomies.26 The study demonstrated a significant benefit in quality of life, symptom relief, and patient satisfaction in the surgical treatment at 2-year follow-up in groups 2 and 3.26 In group 1, sclerotherapy produced an incremental benefit over conservative therapy.26 Surgery was found to be more cost-effective than conservative management in patients with C2 disease.26 Injection sclerotherapy also appeared to be cost-effective for patients with superficial venous reflux but was found to produce less benefit compared with surgery.

The most recent guidelines from the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum recommend against conservative therapy alone for patients with C2 and C3 disease when there is a compelling indication for saphenous stripping or ablation.17 These guidelines also highlight the lack of scientific evidence to support the initial period of conservative therapy mandated by many health insurers in patients who are suitable candidates for surgical therapy.17

Gradient Compression Stockings in C4-C6 Disease

The class 3 gradient elastic stockings are the standard of care in advanced disease (C4-C6).17 The authors of a cohort study from Oregon Health Sciences University reported a 15-year experience in 113 patients with C4-C6 disease who were treated with initial bed rest, ulcer débridement, dressing changes, and class 3 compression stockings.27 Ulcer healing took an average of 5.3 months, occurring in 97% of compliant patients, with a 16% recurrence rate.27 The 2012 update of a Cochrane review from Nelson et al28 specifically assessed the effects of compression therapy in preventing ulcer recurrence. Four trials (979 patients) were identified. In one trial (n = 153), recurrence rates were significantly reduced in the compression group at a 6-month follow-up.28 No difference was noted between high compression and moderate compression in ulcer recurrence in the other three trials. Moderate compression stockings were associated with a higher compliance to therapy.28

Patient compliance with compression therapy is both critical to the successful treatment of chronic venous insufficiency (C3-C6), particularly in patients with C4-C6 disease, and at the same time one of the biggest challenges for patients, particularly those with advanced age, obesity, and arthritis. Patients must be educated about the importance of therapy with ongoing reinforcement of this concept.28 Aids have been developed to allow application of stockings in patients who are challenged; sleeves and metal frames (Fig. 56-1) have been designed and are currently available on the market, although many insurers do not cover these adjuncts.

Figure 56-1 Metallic frames and plastic sleeves have been designed to facilitate the application of graduated compression stockings. (From Moneta GL, et al: Chronic venous disorders: nonoperative treatment. In Cronenwett JL, Johnston KW, editors: Rutherford’s vascular surgery, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders Elsevier.)

CircAid Garment

The CircAid (Fig. 56-2) is a nonelastic compression appliance with multiple, stiff, pliable, adjustable Velcro bands. The system is as effective as compression stockings in reducing edema and promoting venous pump function and may be recommended in patients who are unable or unwilling to wear class 3 stockings.29 In a small prospective randomized trial including 22 extremities with advanced chronic venous disease (C6) from Villavicencio et al, the CircAid system was found to have a significantly faster ulcer healing rate compared with a four-layer elastic bandage.30 The CircAid system allows adjustment for limb size changes, ease and speed of application with improvement of comfort, and tolerance compared with compression stockings and bandaging.

Unna Boot

The Unna boot was first developed by the German dermatologist Paul Gerson Unna at the end on the 19th century. It consists of a multilayered compression dressing made of an inner layer of gauze bandage impregnated with calamine, zinc oxide, glycerin, sorbitol, gelatin, and magnesium aluminum and an outer layer of an elastic wrap exerting a graded compression.

The bandage stiffens with drying, with improvement of venous return during ambulation and edema. The pressure exerted may vary from 50 to 60 mm Hg. The dressing is changed weekly or sooner, depending on the amount of drainage.31

In a 15-year retrospective survey of 998 patients with venous ulcers, the Unna boot achieved a 91% healing rate for first-time ulcers and overall 73.3% healing rate in compliant patients. All the patients were treated 12 times in 32 weeks.31 The overall wound healing rate was superior with the Unna boot compared with polyurethane dressings in a multi-institutional randomized study.32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree