40 Chronic Mesenteric Ischemia

Diagnosis and Intervention

Introduction

Introduction

Although the most common vascular disorder involving the intestines is ischemia, the clinical syndrome of chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI) or chronic intestinal ischemia is very unusual. Other etiologies associated with this uncommon syndrome include fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), Buerger’s disease, and aortic dissection, but atherosclerosis is by far the most common etiology. Atherosclerotic disease of the aorta with associated aorto-ostial stenosis of the visceral vessels is a relatively common angiographic finding but an infrequent clinical problem. In a population-based prevalence study of mesenteric artery stenosis, 553 healthy Medicare beneficiaries were screened with abdominal ultrasound for evidence of mesenteric disease.1 Significant (>50% diameter stenosis) narrowing of a mesenteric vessel, in by far the most instances (>97%) isolated celiac artery narrowing, was detected in 17.5% of the total cohort. There was no correlation with age, race, gender, or body mass index and the presence of mesenteric artery stenosis. Only 1.3% of the patients had involvement of more than one mesenteric vessel. Another natural history study reported on a group of 980 asymptomatic patients with mesenteric ischemia who were followed clinically.2 Only three patients eventually developed symptoms, and in each three mesenteric vessels were severely affected. The most likely explanation for the infrequent occurrence of CMI in clinical practice is the redundancy of the visceral circulation, with multiple interconnections between the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA).

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

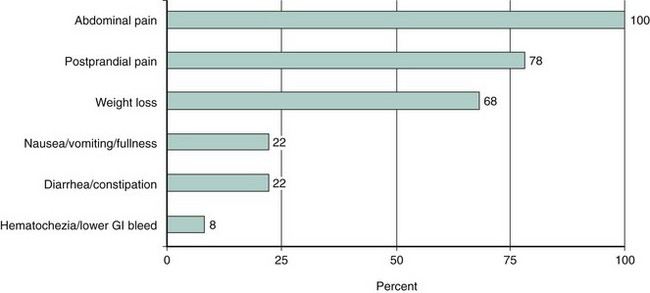

Women are much more commonly affected (70%) than men. The classic presentation of this disease is postprandial abdominal discomfort with significant weight loss (Fig. 40-1). The abdominal discomfort associated with eating leads these patients to avoid food; therefore they lose weight. Patients with CMI typically avoid food and demonstrate significant weight loss. In addition, however, patients with ischemic gastropathy may manifest atypical symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, ischemic colitis, and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Most patients will have evidence of atherosclerosis in other vascular beds and may have suffered prior myocardial infarction, stroke, or claudication. Patients with atypical symptoms may be very difficult to diagnose, but a high degree of suspicion for CMI in those with other manifestations of atherosclerosis and unexplained weight loss is appropriate. Often the diagnosis is delayed in patients who are being evaluated for a possible malignancy as an explanation for their weight loss. Patients with functional bowel complaints rarely experience significant weight loss, which helps to differentiate them from CMI patients. Evidence of significant obstruction of two or more of these vessels is often found when classic symptoms and endoscopy suggest bowel ischemia,3 although single-vessel disease, usually of the SMA, has been described, particularly if collateral connections have been disrupted by prior abdominal surgery.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CMI is a clinical one, based upon symptoms and consistent anatomic findings. Where there is a high clinical suspicion for CMI, patients should undergo Doppler ultrasound (duplex) imaging or noninvasive angiography with computed tomographic angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) to confirm their anatomy. The ability to visualize the mesenteric vessels with duplex ultrasound is technically challenging and requires a skilled, dedicated technologist. The reported accuracy for duplex imaging in identifying significant stenoses of the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries approaches 90%.4,5 With the relatively common application of CTA and MRA imaging for abdominal pathology, it is now possible to make the “anatomic” diagnosis without performing an invasive procedure.6 Invasive digital subtraction angiography is useful for diagnosis but requires a lateral aortogram to visualize the ostia of the mesenteric vessels (Fig. 40-2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree