Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction (Obliterative Bronchiolitis, Chronic Vascular Rejection, and Restrictive Allograft Syndrome)

Anja C. Roden, M.D.

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

Joseph J. Maleszewski, M.D.

Chronic Lung Allograft Disease

The current understanding of the different pathologic manifestations (“phenotypes”) of chronic rejection of the lung is evolving. From a pathologic standpoint, chronic rejection has been considered to affect either the airways (obliterative bronchiolitis, which is fairly well characterized) or the vessels, especially arteries (chronic vascular rejection).1

Similar to the heart, the diagnosis is not generally made on biopsy samples. In contrast to the heart, where chronic rejection is synonymous with chronic allograft vasculopathy, very little is understood or reported on vascular rejection of the lung. Chronic rejection of the lung has, until recently, denoted obliterative bronchiolitis, resulting clinically in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Recently, it has been appreciated that chronic parenchymal lung rejection may have a restrictive component, which is termed restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS). RAS overlaps clinically and pathologically with pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (see Chapter 20). Because of the overlap of obstructive and restrictive disease that characterizes chronic rejection of the lung, the general term “chronic lung allograft dysfunction” (CLAD) has been suggested.2

Obliterative Bronchiolitis

Constrictive or obliterative bronchiolitis is a form of small airway disease characterized by concentric peribronchiolar fibrosis. The term “obliterative” is preferred in the setting of lung transplantation.3 A similar histologic process, usually termed constrictive bronchiolitis, occurs in autoimmune syndromes, allogeneic stem cell transplant, and after inhalational lung injury.4

Obliterative bronchiolitis represents about one-half of chronic lung rejection and two-thirds of irreversible forms.2 The risk is 70% at 10 years posttransplant5,6 and 50% after 5 years.2 The strongest risk factor for allograft failure due to bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome is lymphocytic bronchiolitis (acute small airway rejection, ISHLT grade B1R or B2R) diagnosed by transbronchial biopsy. A patient with a single B2R lesion has a 75% chance of developing bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome in the subsequent 3 years and a 50% chance of dying.7

Clinically, pulmonary function tests reveal respiratory obstruction manifest by normal or decreased forced vital capacity (FVC), reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), and reduced ratio of FEV1 to FVC, without significant response to inhaled bronchodilators. Total lung capacity is normal, and air trapping results in

high residual volume.4 The bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome occurs more frequently in transplant patients with a history of acute cellular rejection, circulating donor-specific antibodies, gastroesophageal reflux disease and microaspiration, and respiratory viral infections. Microvascular insufficiency secondary to the lack of allograft bronchial arteries is also a possible cause.8 Other risk factors include primary graft dysfunction, lymphocytic bronchiolitis, autoimmunity, and genetic factors.9

high residual volume.4 The bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome occurs more frequently in transplant patients with a history of acute cellular rejection, circulating donor-specific antibodies, gastroesophageal reflux disease and microaspiration, and respiratory viral infections. Microvascular insufficiency secondary to the lack of allograft bronchial arteries is also a possible cause.8 Other risk factors include primary graft dysfunction, lymphocytic bronchiolitis, autoimmunity, and genetic factors.9

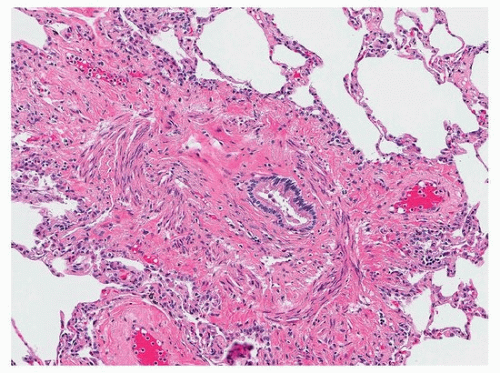

Obliterative bronchiolitis is the pathologic manifestation of the clinical bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome and is characterized by dense hyaline fibrosis in the bronchiolar submucosa, resulting in partial or complete luminal occlusion (Figs. 53.1 and 53.2). It differs from organizing pneumonia in that loose fibrosis within terminal bronchioles is generally absent, and there is destruction of the respiratory epithelium, initially with reactive changes. Evidence of obstruction in the form of extravasated mucus (mucostasis) and foamy macrophages in the distal airspaces may be present and is sometimes the only manifestation of the disease. Because transbronchial biopsies often fail to sample a large number of small airways, a negative biopsy does not exclude the diagnosis. If present, obliterative bronchiolitis in lung allograft biopsies should be reported as ISHLT grade C1.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree