Chronic Heart Failure Management

W. H. Wilson Tang

James B. Young

Overview

Treatment of heart failure is a challenging task that depends on making the proper diagnosis, staging the syndrome severity, and choosing interventions that both diminish suffering and decrease an exceptionally high mortality. Contemporary insight into the pathophysiology of heart failure and a large number of recent clinical trials have given us guidance on utilizing medical and surgical therapies. Greater understanding of the molecular dynamics, humoral perturbation, and circulatory insufficiency characteristic of heart failure will some day lead to even newer and more radical heart failure treatments. Another important paradigm shift in heart failure treatment is early detection of structural heart diseases, such that “preventive” strategies can be implemented before ventricular dysfunction and clinically manifest congestive heart failure develop.

Historical Perspectives

Substantive evolution of treatment paradigms has occurred over the past centuries (Table 87.1). Therapies have evolved from crude attempts to relieve dropsy to suppression of neurohormonal perturbations using combinations of neurohormonal antagonists (1,2). Today, strategies that block or ameliorate adverse remodeling have become the primary focus when considering therapeutic options (3). Indeed, current advances in treatment of the heart failure syndrome include a wide and complicated array of surgical, electrophysiologic, and pharmacologic treatment options.

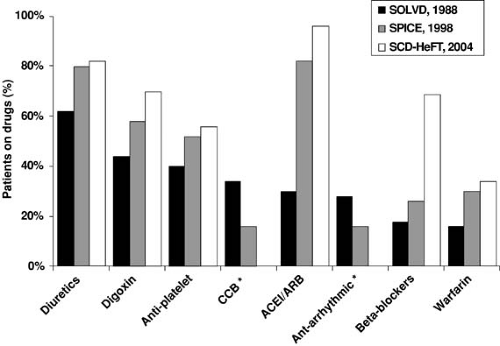

The three most representative (and “equivalent”) cohorts to demonstrate this evolution are (a) Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) in the late 1980s (4), (b) Studies of Patients Intolerant to Converting Enzyme inhibitors (SPICE) trial in the late 1990s (5), and (c) the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) in the early 2000s (6). These data sets document the change in prescription patterns with regard to heart failure since the late 1980s, particularly with the increased use of neurohormonal antagonists such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) and/or β-adrenergic blockers (Fig. 87.1).

Clinical Trials Insights

Tables 87.2 and 87.3 present selected multicenter clinical trials that have greatly shaped our philosophy regarding best approaches to the patients with heart failure. These trials were well performed and therefore provide credible information regarding therapeutic algorithms. A wide spectrum of placebo mortality can be observed, a finding implying that different patient populations have been studied. It is also likely that, over time, patient management strategies have generally improved. The clinical trial data supporting use of specific agents for the heart failure syndrome are discussed in the sections that follow.

Consensus Guidelines

The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) published the first guidelines for evaluating and treating patients with chronic heart failure in 1994 (7,8,9,10,11). Subsequently, guidelines emerged from several cardiology societies as our

knowledge base increased. Recent guideline updates from the European Society of Cardiology, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (12), and the Heart Failure Society of America (13) have further broadened their recommendations regarding issues pertinent to the mildly ill (prevention) or severely ill (end-of-life care) patients.

knowledge base increased. Recent guideline updates from the European Society of Cardiology, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (12), and the Heart Failure Society of America (13) have further broadened their recommendations regarding issues pertinent to the mildly ill (prevention) or severely ill (end-of-life care) patients.

TABLE 87.1 Progress of Understanding of Heart Failure Related to Therapies | |

|---|---|

|

All guidelines support an aggressive approach to diagnosing and treating patients with active ischemia and left ventricular dysfunction. The guidelines are unanimous in recommending ACE inhibitors and ARBs, as well as β-adrenergic blockers in all patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction unless these drugs are contraindicated. All guidelines suggest avoiding agents with incomplete benefit-to-risk profiles, and they remind clinicians about diagnosing and treating underlying and precipitating factors. Furthermore, most of the guidelines emphasize the importance of prescribing nonpharmacologic therapy such as exercise and salt and fluid restriction while addressing patient education about heart failure.

Indeed, many of these recommendations have been further distilled into core performance measures for regulatory agencies to determine the quality of heart failure care in clinical practice (Table 87.4) (14,15,16). However, implementation of guidelines into everyday clinical practice has recognized limitations, because guidelines cannot possibly address all relevant clinical situations (17).

Creating a Management Strategy

Philosophy

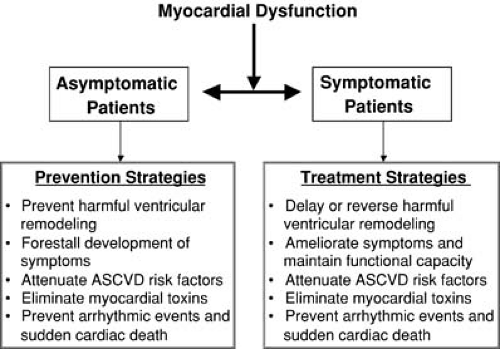

The principles of managing chronic heart failure are rooted in careful evaluation by making the appropriate diagnosis, staging the syndrome, addressing diseases causing or precipitating the difficulty, and using strategies that prevent disease progression. Besides ameliorating symptoms with tailored therapeutic programs, identifying individuals with insidious hemodynamic and hormonal perturbation early on is critical, so therapy can be given early in the syndrome’s course to prevent the development of symptomatic heart failure (Fig. 87.2). Underlying these important principles is the concept that rational polypharmacy is mandatory because these patients are taking multiple drugs and combinations of drugs. The fewest drugs possible should be prescribed and dispensed in such a way that the fewest side effects appear with the most benefit, and cost effectiveness and compliance can be high.

A variety of injurious processes can cause acute or chronic myocardial dysfunction (diastolic or systolic and right-sided or left-sided heart dysfunction). Injured myocytes, because of inotropic and lusitropic dysfunction, are exposed to passive tension and workload demand changes that ultimately translate into increased preload and afterload. This process sets the stage for detrimental cardiac remodeling. Therapies designed to normalize these hemodynamic perturbations seem logical. Less easy to address is myocyte interstitial matrix deposition, which occurs in heart failure and causes stiffening of the myocardium, with all its diastolic dysfunction implications. Strategies (not yet clearly defined) that prevent inflammation and fibrosis may become important with respect to this issue. The aforementioned mechanical alterations produce peripheral vascular bed flow decrement in either subtle or more obvious fashion. Therein lies the attraction of using agents that increase stroke volume (e.g., vasodilators or inotropic agents). The combination of mechanical cardiovascular and peripheral vascular blood flow changes triggers a variety of humoral, neurohormonal, and inflammatory responses, which initially appear to create systemic organ flow compensation. Ultimately, these factors intertwine to precipitate detrimental remodeling of the heart (cardiac hypertrophy and chamber dilation) and to provide targets for therapies that can block molecular factors leading to this remodeling. Because these processes vary in degree from patient to patient, individuals may present without symptoms or may suffer from a variety of fatigue, dyspnea, or fluid retention states that fluctuate based on treatment protocols, diet, physical conditioning, and diseases that caused the problem in the first place. Obviously, findings of potential reversible conditions such as valvular heart disease, coronary artery stenosis, cardiac conduction disturbances, and ventricular or atrial arrhythmias important in the pathophysiology of heart failure need to be surgically or electrophysiologically addressed as well.

TABLE 87.2 Pivotal Clinical Trials Using Drugs Targeting the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System in Chronic Heart Failure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 87.3 Pivotal Clinical Trials Using Drugs Targeting the Sympathetic Nervous System in Chronic Heart Failure | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 87.4 Core Performance Measures for Quality of Heart Failure Care | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Careful Evaluation of Patients

It is critical to remember that patients with heart failure have varied clinical presentations as they move from asymptomatic cardiac dysfunction to symptomatic heart failure. Complicating this issue further is that patients make this transition over highly variable time intervals. Several important questions should be kept in mind when managing patients with chronic heart failure, even before a treatment plan is formulated.

Does the patient actually suffer from heart failure, and are symptoms or physical findings related to this difficulty? Because of the nonspecific nature of clinical findings, many patients with weakness, fatigue, dyspnea, and edema do not have heart failure. Furthermore, patients with heart failure may present

with these symptoms and physical findings, but the symptoms can be related to ancillary comorbidities rather than to cardiac dysfunction (e.g., poorly controlled blood pressure or glucose). Therefore, any patient with symptoms suggestive of heart failure, such as paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, dyspnea on exertion, lower extremity edema, decreased exercise tolerance, unexplained confusion, altered mental status or fatigue in an elderly patient, and abdominal complaints associated with ascites and hepatic engorgement (nausea or abdominal pain), should be evaluated at the bedside. Physical examination is essential to elicit findings supportive of congestive heart failure, such as elevated jugular venous pressure or positive abdominal jugular reflex, a third heart sound, a laterally displaced apical cardiac impulse, pulmonary rales not clearing with cough, and peripheral edema not resulting from simple venous insufficiency (7).

with these symptoms and physical findings, but the symptoms can be related to ancillary comorbidities rather than to cardiac dysfunction (e.g., poorly controlled blood pressure or glucose). Therefore, any patient with symptoms suggestive of heart failure, such as paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, dyspnea on exertion, lower extremity edema, decreased exercise tolerance, unexplained confusion, altered mental status or fatigue in an elderly patient, and abdominal complaints associated with ascites and hepatic engorgement (nausea or abdominal pain), should be evaluated at the bedside. Physical examination is essential to elicit findings supportive of congestive heart failure, such as elevated jugular venous pressure or positive abdominal jugular reflex, a third heart sound, a laterally displaced apical cardiac impulse, pulmonary rales not clearing with cough, and peripheral edema not resulting from simple venous insufficiency (7).

What is the cause of the syndrome? This question forces consideration of diseases that can be treated and eliminated or, at the least, ameliorated, such that progression of the heart failure milieu is halted. Table 87.5 outlines a common list of important clues that can be elicited from careful history or laboratory testing (12).

TABLE 87.5 Evaluation of the Cause of Heart Failure: The History | |

|---|---|

|

What evaluation is needed to confirm the diagnosis and stage the syndrome severity? In individuals with symptoms and physical findings suggestive of heart failure, determination and quantification of left ventricular function are mandated. Echocardiography can provide comprehensive assessment of cardiac structure and performance as well as valvular integrity and synchrony. Electrocardiograms and chest radiographs are also useful diagnostic tests in selected cases. Laboratory testing may reveal the presence of conditions that can lead to or exacerbate heart failure, and natriuretic peptide measurements can further aid in the diagnosis and prognostic determination. Selected patients may benefit from more advanced staging tests such as right-sided heart catheterization, metabolic stress testing, or left-sided heart catheterization and revascularization.

What precipitated the patient’s deterioration? Frequently, medication noncompliance, excessive sodium or fluid consumption, worsening ischemic syndromes, atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, concurrent infection, uncontrolled chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension plunge patients into symptomatic congestive heart failure.

Does the patient take medications that can be detrimental in the heart failure setting? Drugs such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, certain calcium channel blockers, steroids, thiazolidinediones, and Vaughn Williams class I antiarrhythmic drugs may have deleterious effects or cause fluid retention that mimics congestive heart failure.

How should the patient be treated in the short term as well as in the long term, and what is the patient’s expectation? Often, we neglect social factors that play a significant role in morbidity; we should always ask what social support mechanisms can be considered adjunctive nonpharmacologic treatments. Assessment should be made of the patient’s ability to perform routine and desired activities of daily living.

Patient Counseling and Education

As in any chronic disease management, therapeutic success is highly dependent on effective communication between the health care providers and the patient. Ongoing nonpharmacologic interventions are often overlooked. Table 87.6 presents topics for patient, family, and caregiver education and counseling that have been modified from the AHCPR guidelines (11). These guidelines further highlighted the important role of family members or other caregivers in the treatment plan.

Discussion of the cause or probable cause of heart failure is important, as are expected symptoms, symptoms that herald worsening heart failure, and strategies to pursue if symptoms worsen. Furthermore, prognosis should be frankly discussed, and advanced directives should be elicited when appropriate. Advice should be given to family members with regard to resuscitation efforts should sudden cardiac death syndrome occur. The following topics should be reviewed at every visit:

Self-monitoring. It is good practice to provide forms to record medication consumption, pulse rate, blood pressure, and daily weights. Instruction with regard to self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with diabetes is equally important.

Diet counseling. Patients with heart failure are often salt sensitive and frequently benefit from a 2.5 g per day sodium restriction (2.0 g per day in advanced congestive states). Fluid restriction is often recommended but controversial; it is more likely to be effective in hyponatremic states (usually ∼1.5 L per day). General nutritional counseling, especially in patients with underlying diabetes or metabolic

abnormalities (e.g., cachexia), can be helpful. Malnutrition and malabsorption can be common, especially in congestive states. Although many patients may inquire about the role of vitamins and micronutrients in heart failure management (e.g., coenzyme-Q, carnitine, and other antioxidants), clinical data to support their use have been sparse.

Medication compliance and smoking and alcohol cessation. Optimization of compliance with treatment and care plans is important. One should be specific when discussing patient responsibilities with regard to cessation of tobacco and alcohol use. However, well-controlled studies on the benefits of alcohol abstinence in patients with heart failure are few.

Exercise prescription. Exercise should be encouraged in patients with heart failure, usually in a gradually progressive format. Patients should be encouraged to perform aerobic activities that are symptom limited. Activity recommendations need to focus on benefits of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation programs.

Other preventive measures. Vaccinations at appropriate intervals against influenza and pneumococcal disease should be administered. One should not ignore the importance of education with regard to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factor modification.

TABLE 87.6 Suggested Topics for Patient, Family, and Caregiver Education and Counseling | |

|---|---|

|

Pharmacotherapeutic Approaches

Table 87.7 outlines the major drug classes and commonly used drugs and their doses. At the core of therapy for systolic dysfunction are ACE inhibitors and β-adrenergic blockers. If an ACE inhibitor cannot be used because of intolerance or undesirable pharmacologic effects, one should consider ARBs or the combination of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate. Digoxin and diuretics can be added when signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure are present. Long-acting nitrate preparations may be important for dyspnea relief. In individuals with congestive heart failure but preserved left ventricular systolic function, the choice of drugs remains highly contentious.

Specific Therapies

Digitalis Glycosides (Digoxin)

Digitalis glycoside (or foxglove), often referred to as digoxin, is a competitive inhibitor of sodium/potassium/adenosine triphosphatase on the cardiac myocyte cell membranes that causes an increase in intravascular sodium and calcium. Digitalis has several pharmacologic effects that make it attractive in heart failure: (a) positive inotropic action, (b) negative chronotropic effects, (c) modulation of neurohormonal factors (by increasing baroreceptor sensitivity), (d) attenuation sympathetic nervous system tone, (e) reduction in norepinephrine concentration, and (f) diminution of renin-angiotensin levels (18). It is not clear which of these factors predominates in patients receiving low to moderate doses of digitalis (19).

Controversy about using digoxin has centered on proper patient selection and drug dosing (20,21,22). Little debate exists regarding its utility in patients with congestive heart failure who have atrial fibrillation (23). Higher plasma digoxin concentration has been associated with greater rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation (24), and it can be a particularly useful drug when there is a concern about the negative inotropic effects of other rate-controlling agents in congested patients. This is especially useful in the setting of rapid atrial fibrillation in patients who are significantly volume overloaded with marginal hemodynamics.

In the SOLVD Registry, 65% of patients with an ejection fraction of less than 20% were receiving digoxin compared with only 29% with ejection fractions of 36% to 45% (4). Two early, double-blind randomized studies, the Prospective Randomized Study of Ventricular Failure and the Effect of Digoxin (PROVED) (25) and the Randomized Assessment of Digoxin on Inhibitors of the Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (RADIANCE) (26), demonstrated that digoxin therapy was related to improved ventricular performance and median exercise times regardless of serum concentrations. Pooled analysis of outcome in patients from both trials demonstrated that the lowest probability of treatment failure was seen in patients treated with the triple-drug combination of diuretics, diuretics, and ACE inhibitors (18). Furthermore, both trials suggested that withdrawal of digoxin in stable patients with heart failure was associated with higher adverse event rates, and that stopping this drug should be avoided unless the risks outweigh the benefits.

When patients were divided into tertiles of serum digoxin concentration (0.5 to 0.9 ng/mL; >0.9 to 1.2 ng/mL; >1.2 ng/mL), there was a dose-dependent reduction of median exercise time after placebo was substituted for digoxin (27).

When patients were divided into tertiles of serum digoxin concentration (0.5 to 0.9 ng/mL; >0.9 to 1.2 ng/mL; >1.2 ng/mL), there was a dose-dependent reduction of median exercise time after placebo was substituted for digoxin (27).

TABLE 87.7 Common Drugs Used in Managing Chronic Heart Failure in the United States | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||