Chronic Fibrosing Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias

Marie-Christine Aubry, M.D.

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

Seth Kligerman, M.D.

Usual Interstitial Pneumonia/Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

Terminology

Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) is a form of diffuse parenchymal lung disease characterized by patchy subpleural and basal remodeling of lung tissue with honeycomb change. UIP is a pathologic process, also referred to as pattern, that can be seen in a variety of clinical settings such as connective tissue disease (CTD) and drug toxicity.

Familial pulmonary fibrosis and Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome also cause pulmonary fibrosis similar to UIP.

UIP is most commonly seen as the pathologic correlate of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). By definition, IPF requires the exclusion of other known causes of diffuse parenchymal lung disease and the presence of UIP by high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) or by surgical lung biopsy.

General Clinical Features

The prevalence and incidence of IPF are difficult to ascertain due to lack of large-scale studies and the variations in the definition of IPF over the years. Therefore, the estimates of incidence and prevalence are quite broad with reported incidence ranging between 4.6 and 16.3 per 100,000 and prevalence between 2 and 42.7 per 100,000.

Although by definition IPF is idiopathic, there are several potential risk factors described, including cigarette smoking, chronic aspiration, advanced age, male gender, family history of chronic lung disease, and exposures. Environmental exposures linked to the development of IPF include metal dust, wood dust, livestock, textile dust, stone and sand, and wood fires.1 Genetic factors also play a role as a familial history of IPF can be elicited in about 5% of patients. Criteria for considering familial pulmonary fibrosis are varied, but in general, there must be features of UIP by HRCT with or without histologic confirmation in at least two first-degree family members, or a confirmed case of UIP with a history of two other affected relatives. Autosomal dominance is suspected in most cases. Age of onset is younger than that of nonfamilial IPF, and disease progression is more rapid. There are no consistent imaging or histologic differences between familial and nonfamilial forms of the disease.2 Heterozygous mutations in TERT, TERC, SFTPC, and FTPA2 account for about 20% of familial interstitial pneumonias.3

These cases are still classified as idiopathic interstitial pneumonias.

In IPF, men are more commonly affected than are women, and the mean age at onset is around 60 years, with a history of prior respiratory symptoms typically measured in months to years. The symptoms are not specific and comprise exertional dyspnea and nonproductive cough. Physical exam typically reveals bibasilar inspiratory crackles qualified as Velcro-like. Digital clubbing is common. In young adults, the diagnosis of UIP should raise the possibility of familial disease, occult collagen vascular disease, or occult inhalational exposure. Pulmonary function tests reveal restriction with decreased lung volumes and total lung capacity, normal or increased FEV1/FVC (unless the patient has combined chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and/or decreased diffusing capacity.

Radiologic Findings

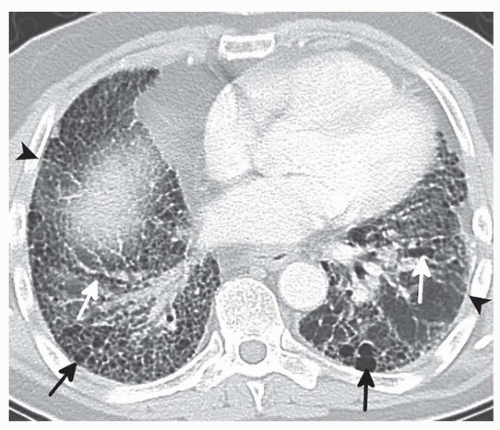

HRCT may be used to diagnose IPF in the absence of pathology if all features of UIP are identified. These features include (1) subpleural, basal predominance, (2) reticular abnormalities, (3) honeycombing with or without traction bronchiectasis, and (4) the absence of atypical features (Fig. 17.1).4,5 The atypical features that are described as inconsistent with UIP include an upper lobe predominance, peribronchovascular predominance, micronodules, discrete cysts

distinct from honeycombing, mosaic attenuation representing air trapping, or consolidation. Although extensive ground-glass opacity is also considered an atypical feature, it can be seen in cases of accelerated IPF. Honeycombing is a hallmark of UIP and appears as stacked subpleural cysts.6 Surgical biopsies are typically performed in cases of HRCT atypical features, often the lack of honeycombing. Histology-proven UIP is demonstrated in up to 25% of these cases.5

distinct from honeycombing, mosaic attenuation representing air trapping, or consolidation. Although extensive ground-glass opacity is also considered an atypical feature, it can be seen in cases of accelerated IPF. Honeycombing is a hallmark of UIP and appears as stacked subpleural cysts.6 Surgical biopsies are typically performed in cases of HRCT atypical features, often the lack of honeycombing. Histology-proven UIP is demonstrated in up to 25% of these cases.5

Prognosis and Treatment

Patients with IPF have a progressive illness that is eventually fatal, and the only treatment is lung transplant. There is currently no proven pharmacologic treatment for IPF. Therefore, IPF needs to be distinguished from all other IIPs, in particular from NSIP since NSIP has a better prognosis. The 5-year survival for IPF is 30% to 50%, with slight improvement among patients with “discordant” UIP (present in only 1 or 2 lobes on biopsy).7 In another study, IPF had a median survival of 40 months after diagnosis, with a 1- and 3-year mortality rate of 17% and 43%, respectively. This is in contrast to patients with UIP related to a specific etiology such as autoimmune CTD; survival was far better, with a median survival of 143.8 months, 1-year mortality rate of 7.9%, and 3-year mortality of 13.9%.8 Other factors that may affect survival negatively in patients with IPF include male gender, combined emphysema, pulmonary hypertension, carbon monoxide diffusing capacity of < 60%, and decline in the FVC over 6 to 12 months.

Most patients with IPF experience a slowly progressive decline. Some patients may experience rapid progression, remain stable for many years, or experience sudden acute worsening of their symptoms known as accelerated or acute exacerbation of IPF. Lung cancer is a known complication of patients with IPF but does not seem to impact the overall survival of these patients.

Gross Findings

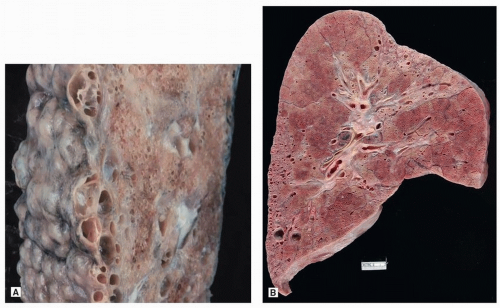

External examination demonstrates typical features of “cobblestone” pleura, caused by interstitial fibrosis (Fig. 17.2A). Cut section demonstrates patchy scarring, usually with cysts, in a predominantly subpleural distribution (Fig. 17.2B). Findings are more prominent in the lower lobes. When the upper lobes are involved, the abnormalities will be more prominent in the lower zones.

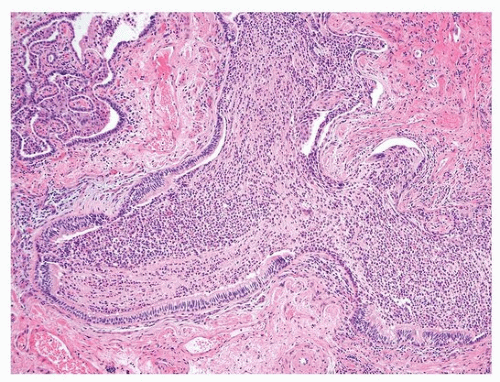

Microscopic Findings

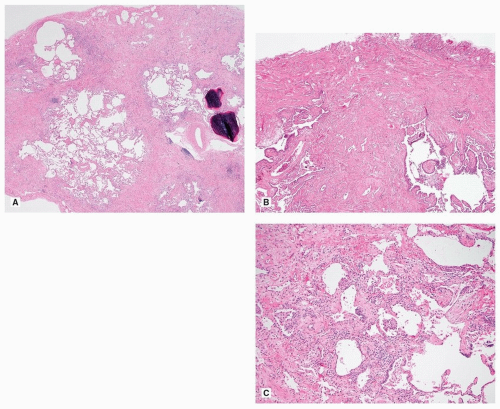

The diagnosis of UIP stems on the presence of three major histologic features: (1) fibrosis with architectural distortion (with or without honeycombing) in a subpleural and/or paraseptal distribution, (2) patchy involvement, and (3) fibroblast foci (Fig. 17.3). These features should be present, for a definitive pathologic diagnosis, in the absence of several negative histologic features: granulomas, predominant airway-centered disease, and prominent interstitial inflammation away from honeycombed areas. The overall appearance of UIP is strikingly heterogeneous due to the juxtaposition of scarred lung next to normal lung, of marked fibrosis and architectural distortion next to mild interstitial fibrosis, and of old collagen fibrosis next to young cellular fibrosis in the form of fibroblast foci. This heterogeneity is extremely helpful for the differential diagnosis with other fibrosing parenchymal lung diseases, in particular nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). This heterogeneity is appreciable with the naked eye and at very low power. Honeycomb lung is characterized by enlarged airspaces with thick fibrotic wall, lined by reactive bronchiolar epithelium or occasionally squamous metaplastic epithelium. In the areas of fibrosis, it is common to see other features such as ossification and smooth muscle cell hyperplasia.

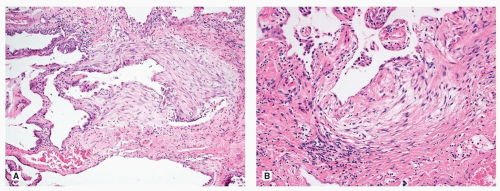

The interface between the collagen fibrosis and the normal or less involved lung is where the fibroblast foci are typically found. They are composed of fibroblasts forming small dome-shaped lesions. The fibroblasts are arranged in a linear arrangement and present in a pale myxoid stroma. The foci are lined by cuboidal epithelial cells (Fig. 17.4). Increased numbers of fibroblast foci have been associated with worse outcome in some studies.

Although fibroblast foci need to be distinguished from other acute lung injuries such as diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) and organizing pneumonia (OP), in patients with accelerated IPF, DAD or OP is present, superimposed on the underlying UIP.

Chronic inflammation is present but normally overshadowed by the fibrosis. Peribronchiolar lymphoid aggregates may be seen; however, any significant peribronchiolar airway-centered fibrosis and inflammation should raise the consideration of alternative diagnosis such as chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia (HP). The dilated airspaces of honeycombing are often filled with mucus and acute inflammation and do not constitute acute bronchopneumonia (Fig. 17.5).

Occasionally, prominent airspace accumulation of eosinophils resembling eosinophilic pneumonia can be present. The significance of this finding is unclear but can be seen in cases of UIP related to drug toxicity.

In a smoker, airspace accumulation of smokers’ macrophages is common and may resemble desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP-like). Vascular remodeling secondary to the fibrosis is typical in UIP. Common vascular changes include intimal fibrosis and medial hypertrophy of arteries with variable intimal thickening. Veins and venules may also be affected resulting in increased alveolar septal capillaries and hemosiderin deposition resulting in pulmonary venoocclusive disease (PVOD)-like changes. These findings lead to pulmonary hypertension, which, however, needs clinical confirmation with echocardiogram.9

Occasionally, in cases of multiple lung biopsies, histologic features of UIP may be seen in one site while features of NSIP may be seen in another. This has been referred to as “discordant” UIP, but for practical purpose, the final diagnosis may simply be UIP.

UIP is a common histologic finding in patients with autoimmune CTD, including rheumatoid arthritis, followed by systemic sclerosis, Sjogren syndrome, dermatomyositis-polymyositis, and undifferentiated CTD.8 Often, UIP in CTD is identical to UIP in IPF. In one series, the histologic findings of UIP in 9 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (4), polymyositis-dermatomyositis (2), mixed CTD (1), systemic lupus erythematosus (1), and systemic sclerosis (1) were compared to those of 99 patients with IPF.10 In this study, the number of fibroblastic foci was significantly greater in the IPF group.10 However, by itself, this feature cannot be used to distinguish CTD-associated UIP from UIP in IPF. Additional findings of follicular bronchiolitis and pleural lymphoid inflammation are seen at higher rates and raise the possibility of CTD.

Tissue Sampling

Open or video-assisted stereoscopic lung biopsy is most important in those patients with an uncertain diagnosis and those thought unlikely to have IPF by HRCT.11 Lungs should be sampled at the edge of grossly abnormal areas avoiding of the tips of the lingula or right middle lobe and sampling of more than one lobe of 3 to 5 cm in greatest dimension is recommended.12 Overall, it has been estimated that fewer than 15% of patients with IPF have tissue diagnosis by open biopsy.13 Although most authorities stress the need for wedge biopsies, there is some utility to transbronchial biopsy in the diagnosis of interstitial lung disease.14 However, findings must be interpreted with caution, as most of the features that are typical of UIP depend on overall distribution and subpleural findings, which are not commonly found in transbronchial specimens.

Occasionally, explanted lungs from patients with UIP who have undergone transplantation will be the first specimen available for pathology examination. There have been two studies comparing open biopsies with explant pathology in patients with UIP, and these have shown some differences between both. Indeed, honeycombing is universal in explants and present to a lesser degree in biopsies.15,16 NSIP-like areas also appear to be more common in explants. Another finding described in explants is interstitial emphysema. Interstitial emphysema is well described as a complication in neonates, with or without mechanical ventilation. It is not as recognized in adults, especially in the context of interstitial lung disease.17 Interstitial emphysema (Chapter 46) results from air dissecting into the lung’s soft tissue and, histologically, appears as cysts lined by fibrous tissue and histiocytic reaction with foreign body-type giant cells.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree