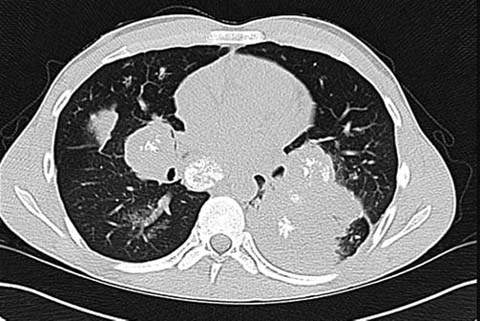

Fig. 1.

An 18-year-old-female presenting with Hodgkin’s lymphoma as a mediastinal mass. The mass is irregular in shape, having lost the normal morphology of the thymus, and is heterogeneous in appearance

On radiography, lymphoma frequently presents as a large anterior mediastinal mass. CT is critical in the initial diagnosis, to evaluate for potential tracheobronchial compromise. Life threatening airway obstruction is seen in up to 10% of patients with mediastinal lymphoma. Endotracheal anesthesia is reported to be safe in patients with lymphoma in the anterior mediastinum when the expected cross-sectional area of the trachea is reduced by no more than 50% [7].

The role of MRI in the initial diagnosis of lymphoma is generally considered to be limited. However, some reports indicate that whole body DWI may be useful in the staging of lymphoma. MRI may also be of value in determining the amount of fibrous stroma in a lymphomatous mass, which can indicate the expected residual mass after treatment [6].

Germ-Cell Tumors

Germ cell tumors are less common masses of the anterior mediastinum, accounting for 6–18% of all mediastinal masses [6]. The majority are benign teratomas (80% of all mediastinal germ cell tumors) [4, 5]. Malignant germ cell tumors in the pediatric population include both seminomatous and non-seminomatous lesions. Seminomatous lesions typically lack serologic markers and usually do not contain internal calcifications. For this reason, seminomas typically require histologic diagnosis. Non-seminomatous germ cell tumors can usually be identified through a combination of imaging appearance, serum markers such as β-human chorionic gonadotropin and -fetoprotein, and clinical symptoms such as precocious puberty [8].

Thymic Neoplasms

Primary thymic neoplasms are typically benign in the pediatric population, with thymolipomas as the most common lesions. Thymolipomas usually present as fat- and soft-tissue-containing lesions of the anterior mediastinum. They typically do not have internal calcifications [9, 10].

Most of the other mass-type lesions arising from the thymus are non neoplastic. Of these, perhaps the most important to consider is benign thymic hyperplasia. In infants, the mean thickness of the thymus is 1.50 cm, with a standard deviation of 0.46 cm. In children over the age of 10 years, the mean thickness of the thymus is 1.05 cm, with a standard deviation of 0.36. An abnormal process should be considered when thymic thickness on cross-sectional imaging is over two standard deviations above normal (upper limits of normal thymic thickness are 2.42 cm from ages 0–10 and 1.77 cm respectively) [4, 11].

The thymus normally atrophies as a result of cytotoxic injury, but may undergo secondary, benign hyperplasia thereafter. This period is referred to as “thymic rebound.” The smooth contours of the hypertrophied thymus and a homogeneous soft-tissue density distinguish thymic re-bound from tumor recurrence [6] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A 16-year-old female with thymic rebound after undergoing chemotherapy for a sarcoma of the lower extremity. The margins of the thymus are preserved and the thymus is homogenous in appearance

Middle Mediastinal Neoplasms

The most common primary pediatric middle mediastinal neoplasms are lymphomatous or leukemic [4, 5]. Otherwise, primary middle mediastinal neoplasms are unusual in the pediatric population. Other neoplasms of the middle mediastinum include cardiac tumors, which are rare, and metastatic disease, which is more common. The majority of middle mediastinal masses in the pediatric population are either infectious, inflammatory, or congenital (such as bronchopulmonary foregut cysts; discussed below) in origin.

Cardiac Tumors

Cardiac tumors are rare in the pediatric population. The most common pediatric tumor is a cardiac rhabdomyoma which is usually seen in association with tuberous sclerosis. In one series, 91% of cardiac rhabdomyomas were found in association with tuberous sclerosis. In general, any intracavitary mass found in infants should be considered a rhabomyoma until proven otherwise [13, 14].

Foregut Cysts

The most frequently encountered developmental anomaly of the pediatric middle mediastinum is the foregut cyst, which may be bronchogenic, enteric, or neurenteric. As a group, foregut cysts comprise 11% of mediastinal masses in children [4, 5]. It can be difficult to precisely determine the structure of origin associated with a foregut cyst, but it is often the structure that the cyst is most closely associated with anatomically. The CT appearance of foregut cysts is typically diagnostic. Most foregut cysts are welldefined, well-circumscribed, homogeneous, fluiddensity structures, although internal proteinacious debris can confer them with a hyperdense CT appearance [4, 5].

Lymphadenopathy

Lymphadenopathy, either in association with lymphoma or with an infectious or inflammatory process, is often encountered in the middle mediastinum. Identifiable mediastinal lymph nodes in infants are typically abnormal. In adolescents, lymph nodes 1 cm in their short axis are typically considered abnormal [4, 15].

Posterior Mediastinal Neoplasms

Neurogenic Tumors

Neurogenic tumors make up approximately 90% of posterior mediastinal masses in the pediatric population [6]. Tumors of ganglion-cell origin include neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma. Neuroblastoma is most common amongst infants and young children with a median patient age at presentation of 2 years (Figs. 3, 4). Ganglioneuroma, typically a benign lesion, occurs in older children with a median age at presentation of 10 years. For ganglioneuroblastoma, the median age at presentation is 5.5 years [6, 16].

Fig. 3.

A 3-month-old male with a partially calcified posterior mediastinal mass found to be a neuroblastoma. Normal thymic tissue is seen anteriorly

Fig. 4.

Bilateral apical masses in a 2-year-old male with neurofibromatosis type I. Post-contrast coronal MRI shows prominent peripheral enhancement in both lesions.

All three tumors of ganglion cell origin typically appear as a vertically elongated mass with tapered superior and inferior margins. Internal calcifications are seen in 30% of ganglion cell origin tumors and adjacent bony changes are common [17].

Peripheral nerve sheath tumors, schwannomas, and neurofibromas, are generally indistinguishable by imaging criteria alone. Schwannomas are encapsulated tumors that lack nerve fibers. Neurofibromas are non-encapsulated and contain nerve fibers. Both masses are generally well-demarcated and spherical/lobulated in appearance. Both are associated with a “targetsign” appearance on T2 weighted MRI sequences, consisting of peripheral T2 bright sequences and internal T2 dark signal. Schwannomas and neurofibromas are usually associated with the diagnosis of neurofibromatosis [4, 6, 18].

Approximately 5% of peripheral nerve sheath tumors undergo malignant degeneration, characterized by large size, central necrosis, and restricted diffusion on DWI sequences [6].

Primary Pulmonary Neoplasms

Pleuropulmonary Blastoma

Pleuropulmonary blastoma (PPB) is a rare entity that has recently been separated from the adult pulmonary blas-toma. It is considered to be a dysontogenetic tumor, such as Wilms’ tumor of the kidney, neuroblastoma, or hepa-toblastoma [19]. The imaging appearance of PPB has been described primarily in a series of case reports. PPB is typically quite large on presentation, probably because of the late diagnosis. These tumors can be a solid lesion, mixed solid and cystic, or predominantly cystic. Most are heterogeneous in appearance and pleural-based. For rea-sons that are unclear, PBB most frequently occurs in the right hemithorax, with 70% of reported cases being right-sided [19].

Carcinoid Tumor

The vast majority (80–85%) of primary malignant lung tumors in children are carcinoid tumors, with approximately 85%, of them occurring within the tracheo-bronchial tree [20, 21]. These are endoluminal lesions that are often associated with internal calcifications, and therefore with post-obstructive atelectasis or pneumonia. Presenting symptoms typically include cough, hemoptysis, or recurrent pneumonia. Carcinoid tumors are often spherical, lobulated, or elongated along the axis of the associated bronchi. Their typically prominent internal contrast enhancement is helpful in distinguishing these tumors from mucus plugs [20, 22].

Metastatic Pulmonary Neoplasms

The most common pediatric pulmonary neoplasm is metastatic disease (Fig. 5). Metastatic disease can involve the pulmonary structures through hematogenous spread, lymphatic spread, or direct extension. Renal malignancies in particular, such as Wilms’ tumor, can invade the chest by direct extension in the renal veins and inferior vena cava [15].